When a person opens a website, they are not only downloading content: within milliseconds, they also provide a highly detailed technical portrait of their device, environment, and browsing habits. All of this happens without clicking “Accept Cookies,” without logging in, and often even in incognito mode.

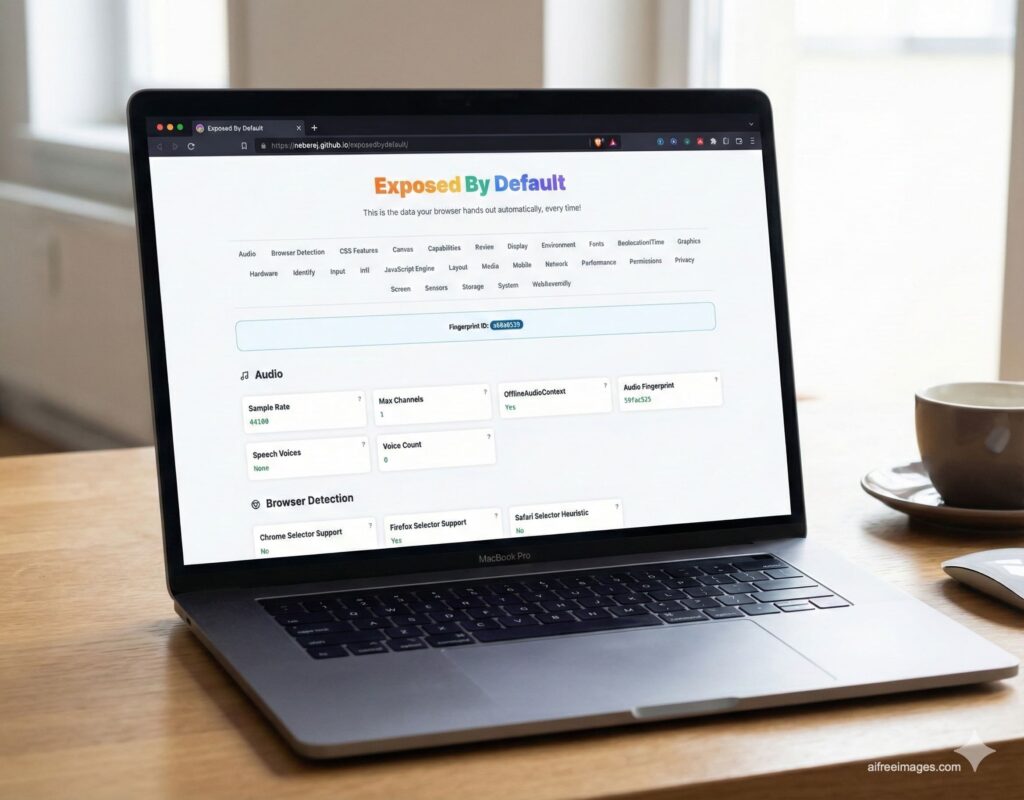

A recent open-source demo, Exposed by Default, clearly demonstrates this: as soon as you visit, dozens of parameters that the browser automatically reveals scroll across your screen. The end result is an almost unique digital fingerprint, capable of distinguishing a device among millions — making it ideal for advertising systems, advanced analytics, or risk profiling.

More than Cookies: Fingerprinting as a New Identity Card

For years, privacy discussions centered on third-party cookies. But the advertising industry and major platforms are now playing a different game: browser fingerprinting.

The concept is simple yet worrying. Instead of storing an identifier on your device (like a cookie), websites measure how your browser and environment are configured:

- CPU model and architecture (ARM or x86_64), number of cores, and approximate memory.

- Screen resolution, window size, pixel density, aspect ratio.

- Installed font set and their internal metrics.

- Time zone, system language, number and date formats.

- Multimedia capabilities (codecs like AV1, HEVC, or VP9).

- JavaScript engine behavior through small performance tests.

- Graphics details from Canvas and WebGL (how the same object is rendered on your specific GPU).

- Permission statuses (camera, microphone, notifications, sensors).

- Support for modern APIs such as WebCodecs, WebGPU, WebRTC, local storage, etc.

Individually, each piece of data may seem harmless. But combined, they form such a specific information vector that it’s statistically highly unlikely for two devices to have identical fingerprints. That is the fingerprint: a kind of technical ID that doesn’t rely on cookies and remains even if the user “cleans” the browser.

Exposed by Default: An Uncomfortable Mirror of What Happens in the Background

The Exposed by Default project acts as a mirror. All code runs on the client side, sends nothing to external servers, and does not store profiles. Its goal isn’t to track but to transparently show what any other website could be collecting behind the scenes.

When you visit, the page:

- Detects fonts, language, time zone, and regional settings.

- Runs tests on Canvas and audio to obtain unique hardware fingerprints.

- Checks which advanced APIs your browser supports.

- Verifies subtle behaviors of JavaScript and the graphics engine.

This information generates a Fingerprint ID and practically shows how “unique” your device is within a simulated population of millions of browsers. The exercise is more educational than technical: suddenly, the user sees in black and white what was previously invisible.

What Is All This Information Used For?

In a technological environment, it’s important to understand that this fingerprint isn’t just valuable for advertising:

- Ultra-targeted advertising

Adtech platforms use fingerprinting to recognize the same user even if they change IPs, open new tabs, or delete cookies. This allows them to display consistent campaigns, limit impacts, or apply attribution models. - Behavioral profiles and scoring

Banks, fintechs, and large online retailers combine browser features with usage patterns to feed risk models for fraud detection. An unexpected change in fingerprint can trigger alerts; a “known” fingerprint might lower or raise the cost of a loan, installment purchase, or access to certain offers. - Access control and account management

Many services use fingerprinting to detect shared accounts, suspicious simultaneous logins, or license abuse. A single user attempting to bypass limits can be “marked,” even without traditional tracking. - Moderation and regulatory compliance

In sensitive contexts (e.g., gambling, crypto, adult content), operators combine IP, fingerprint, and other indicators to block regions, comply with regulations, or impose age restrictions and additional verifications.

And, of course, all this information holds direct economic value. Knowing who is who, even without knowing their real name, is the raw material for real-time bidding systems (RTB), Customer Data Platforms (CDPs), and data broker networks.

Is There Really Nothing We Can Do?

The feeling of helplessness is understandable: browser exposing data, IP traveling with each request, obfuscated scripts measuring everything—even the width of the scrollbar… But there are strategies, albeit imperfect:

- Browsers with anti-fingerprint protections

Projects like Tor Browser or Mullvad Browser aim to make all users “look alike.” They restrict APIs, return generic values, and reduce variability. The result: instead of a million unique fingerprints, thousands of users share the same one. - Extensions and script blockers

Blocking third-party scripts, disabling JavaScript by default on unknown domains, or using extensions like JShelter helps cut fingerprinting channels and fake responses for certain APIs. - Less extreme personalization

Installing many rare fonts, exotic extensions, or highly specific configurations makes a device more “unique.” Maintaining at least one browser with a fairly standard setup helps blend into the crowd. - Separate profiles by context

Using different browsers or profiles for banking, work, leisure, and general browsing doesn’t eliminate the fingerprint but segments information: a fingerprint tied only to banking is less “valuable” to advertisers than one that sees everything.

Yet, the uncomfortable reality remains: fingerprinting doesn’t disappear. It can only be made more difficult and costly for trackers. Total protection exists only in very extreme—and impractical—scenarios where most of the modern web is abandoned.

A Technical… and Political Problem

For the tech community, the core message is clear: fingerprinting is no longer just a laboratory curiosity but a structural part of the digital economy. The value of a user isn’t only measured in clicks or cookies but in the ability to recognize them again tomorrow, even if they’ve deleted everything.

In this context, projects like Exposed by Default serve an awkward but necessary role: reminding us that every time we open a tab, we’re not only consuming information but also generating it. Information that someone might turn into targeted advertising, risk models, fraud detection, or access control.

The question left open for legislators, regulators, and browsers is whether notices about cookies and lengthy privacy policies are enough… when the most sensitive data might never pass through those channels.