The cloud may seem ethereal, but its muscle is deeply physical. Every email, every video, every AI model, and every digital transaction ends up landing in a building full of racks, fiber, transformers, and cooling systems. And in the United States, this infrastructure is not evenly distributed: it is overwhelmingly concentrated in a few states that have become true “digital capitals.”

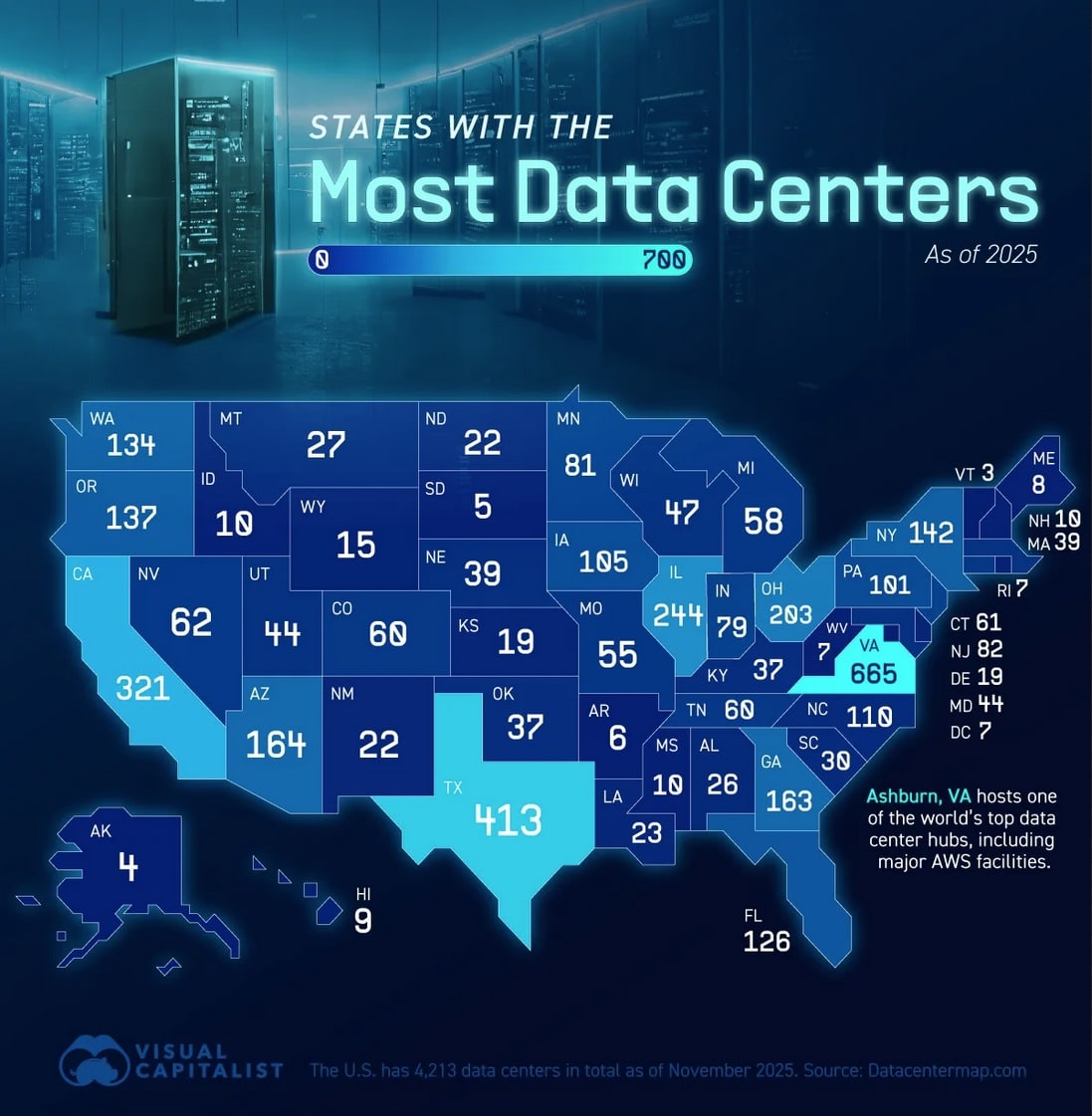

The latest data published by DataCenterMap — one of the most used databases to track the industry’s pulse — paints a clear podium: Virginia leads with 570 data centers listed; Texas is second with 394; and California rounds out the “top 3” with 288.

Why Virginia is the epicenter: the network effect of “Data Center Alley”

Virginia (especially the northern part of the state) is not a coincidence or a recent phenomenon. It’s an example of the “network effect” applied to infrastructure: where there’s already a lot of connectivity, many carriers, and multiple interconnection points, it’s easier for more operators, clouds, and clients to arrive. In this ecosystem, the Ashburn area (in Loudoun County) has earned the nickname “Data Center Alley” due to the density of facilities and its impact on global traffic.

This concentration has historically been accompanied by a favorable industry environment (administrative efficiency, incentives, and a network of specialized providers). The result is an inertia that’s hard to replicate: once a region consolidates as a major hub, any new project benefits from being “close to everything.”

But Virginia’s leadership also has a downside: local debates over electricity consumption, land availability, and water use for cooling have intensified as the scale of projects grows.

Texas is no longer just promising: it’s a real large-scale alternative

If Virginia symbolizes the power of the historic cluster, Texas embodies capacity expansion: more available land, large metropolitan areas with increasing connectivity (Dallas–Fort Worth stands out), and a traditional appeal based on costs and deployment flexibility.

This momentum is reflected in the pace of capacity absorption in major North American markets: sector reports position Dallas–Fort Worth among the demand leaders in North America in recent periods, indicating that deployments are not just announcements but actual square meters (and megawatts) occupied.

However, Texas also faces the same dilemma as other hubs: the bottleneck is no longer “building the facility,” but ensuring energy supply, grid connection, and permits within timelines compatible with the rapid growth of the cloud and AI.

California: still key, but growth is more conditional

California maintains significant importance due to its proximity to the tech ecosystem and local business demand. Still, its narrative is different: the state is less associated with easily replicable mega-projects and more with a mature market where limits (land, regulation, energy) influence the pace of new deployments.

In practice, this does not diminish its strategic importance: latency and proximity to clients still matter, and California remains a relevant node for critical loads and companies operating near major tech hubs.

The “second tier” that determines the country’s resilience

Beyond the top three, states act as regional gears: Illinois (206) and Ohio (195) serve as inland hubs; Georgia (201) as a southeastern hub; Arizona (155) as a growth destination in the southwest; and New York (133) as a northeastern node.

Meanwhile, the Pacific Northwest (Oregon with 121 and Washington with 107) is gaining importance due to a combination that’s highly valuable in data centers: more benign climate for cooling and available energy (with a significant renewable component in some areas).

The big lesson: the new map is written by power, fiber, and permits

If we had to sum up why some states take off while others don’t, the answer fits in three words: power, connectivity, and speed. The sector can design increasingly efficient architectures, but it remains bound by physics: without megawatts, there are no GPUs; without fiber and interconnection points, no competitive latency; without agile permits, no “time to market.”

And this is a lesson that goes beyond the United States. Europe — and specific markets like Madrid — are experiencing similar tensions: competition for industrial land, permitting processes, access to grids, and energy reinforcement plans. The difference is that the U.S. demonstrates, with numbers, how quickly clusters form when these pieces fit together… and how difficult it is to displace them once they’ve created their own momentum.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is “Data Center Alley” and why is it so frequently mentioned in Virginia?

It’s the popular name for the cluster in northern Virginia (Ashburn/Loudoun area), known for its very high concentration of data centers and its dense networks and interconnection points, attracting major operators and cloud providers.

Why is Texas growing so rapidly as a data center destination?

Mainly due to available land, the growth of large urban areas (like Dallas–Fort Worth), and a market dynamic that favors deploying capacity at scale when access to energy and network is secured.

Do data center counts vary depending on the source?

Yes. It depends on whether only operational facilities are counted, or also announced projects, or what is considered a “data center” (campus with multiple buildings, technical rooms, edge sites, etc.). Even within the same database, numbers are updated over time.

How does AI impact where data centers are built?

AI increases energy and cooling demand and pushes capacity concentration in areas with access to megawatts, good connectivity, and quick permits. This reinforces existing clusters and accelerates competition among states to attract investment.

via: marketstatics