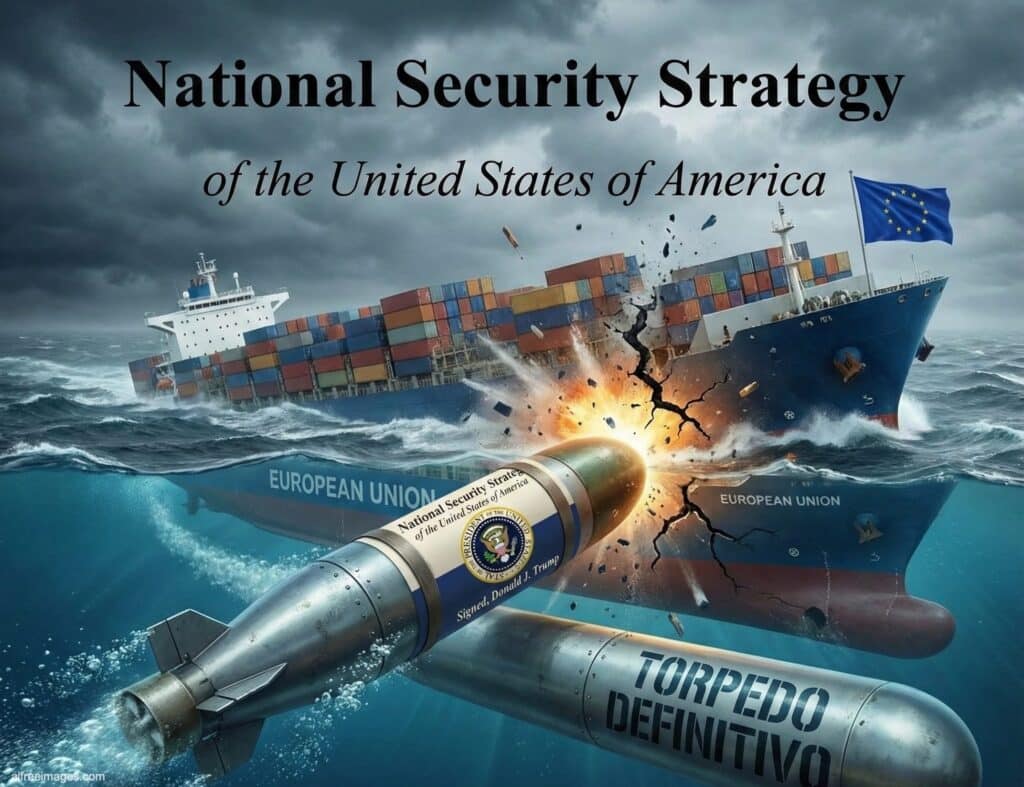

The United States National Security Strategy 2025, signed during Donald Trump’s presidency, is primarily a technological document shaped like a geopolitical text. Beyond references to Europe, China, or the “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, the underlying message for the digital ecosystem is clear: those who control artificial intelligence, semiconductors, digital infrastructure, and cybersecurity will hold a significant portion of the world order in the coming decades.

For a technology enthusiast, the document almost functions as a roadmap of priorities: consolidate dominance in AI, biotechnology, and quantum computing; ensure the supply of semiconductors; harden critical networks against cyberattacks; and leverage the financial and technological power of the United States as a tool of global influence.

Technology Becomes a Vital Interest, Not a Sectoral Issue

In one of the initial sections, the strategy lists the “vital” interests of the United States worldwide. Alongside stability in the Western Hemisphere or security in the Indo-Pacific, there’s a phrase that summarizes the importance of the tech sector: Washington aims to “ensure that American technology and standards—especially in AI, biotechnology, and quantum computing—drive the world forward.”

It’s not just about exporting products but about setting technical standards, protocols, and regulatory frameworks that become global benchmarks. The document assumes that those who set these standards will gain a structural advantage in supply chains, intellectual property, digital platforms, and by extension, political influence.

The description of the “means” available to the U.S. reinforces this idea. Among the country’s main assets, the Strategy includes:

- the “world’s most innovative economy,”

- the “most advanced and profitable tech sector,”

- and a financial ecosystem that enables funding innovation at a global scale.

In other words, software and hardware are no longer seen as just sectors of the economy but as infrastructure of national power, on the same level as the armed forces or alliances.

AI, Quantum, and Autonomous Systems: The Next Generation of Military Power

In the strictly military realm, the document leaves little room for interpretation: the United States wants to maintain and expand its advantage in dual-use and defense technologies, emphasizing domains where it considers itself strongest.

The Strategy explicitly mentions:

- capabilities in submarine, space, and nuclear environments,

- and, above all, technologies that “will determine the future of military power”:

- artificial intelligence,

- quantum computing,

- autonomous systems,

- and the energy sources needed to sustain them.

The message to defense companies, robotics startups, and AI providers is direct: funding and political support will be available for those helping preserve this technological edge—provided they align with the strategic agenda.

At the same time, the White House assumes that a critical part of this race won’t only unfold in laboratories but also in the realm of intellectual property and industrial espionage. This explains the continued emphasis on combating technological theft and cyberespionage, especially in relation to China and the pressure against Europe.

Semiconductors and Taiwan: The Geopolitics of Chips in Black and White

Pocas veces un documento oficial de este nivel reconoce tan directamente la dependencia mundial de un único nodo de fabricación. La Estrategia subraya que la importancia de Taiwán no es solo geográfica, sino también tecnológica, “en parte por su dominio en la producción de semiconductores”.

Esa frase cristaliza lo que el sector lleva años repitiendo: la isla es un punto de apoyo crítico del ecosistema mundial de chips, y cualquier conflicto en el estrecho tendría consecuencias inmediatas para:

- la industria de servidores y centros de datos,

- el mercado de electrónica de consumo,

- el despliegue de infraestructuras de red,

- y la evolución misma de la IA generativa, que depende de GPUs de alta gama.

Que la Estrategia vincule explícitamente semiconductores, rutas marítimas y equilibrio militar en Asia confirma que para Washington la política de chips ya no es solo industrial, sino claramente estratégica. Y envía una señal a fabricantes, fundiciones y proveedores de equipos: la reconfiguración de cadenas de suministro, reshoring y friendshoring no son modas, sino un elemento central de la política de seguridad.

Digital Infrastructure and the “Global South”: Competing with the Chinese Model

Otro eje tecnológico clave es la competencia por las infraestructuras físicas y digitales en el llamado “Sur Global”. El texto reconoce que las empresas estatales y respaldadas por el Estado chino han sabido aprovechar sus excedentes comerciales para financiar:

- redes de telecomunicaciones,

- proyectos de infraestructura física y digital,

- y préstamos vinculados a la construcción de puertos, carreteras o redes eléctricas.

La Estrategia calcula que China ha reciclado alrededor de 1.3 billones de dólares de sus superávits comerciales en forma de créditos a socios. Y advierte sobre los “costes ocultos” de esas ofertas: espionaje, riesgos de ciberseguridad y trampas de deuda, entre otros.

Frente a ello, Estados Unidos propone una respuesta que combina:

- tecnología (ofrecer soluciones propias en redes, IA, energía, o infraestructuras críticas),

- finanzas (aprovechar la profundidad de sus mercados de capitales y el dólar como moneda de reserva),

- y diplomacia económica (coordinarse con Europa, Japón, Corea del Sur y otros aliados que poseen importantes activos en el extranjero).

Para los países africanos, latinoamericanos o del sudeste asiático, el mensaje es que la pelea ya no será solo entre préstamos chinos y multilaterales, sino entre paquetes completos de infraestructura digital, estándares tecnológicos y alineamiento político.

Cybersecurity and Critical Infrastructure: An Inevitable Alliance with the Private Sector

En el capítulo de ciberdefensa, la Estrategia se aleja del discurso genérico y entra en detalles relevantes para cualquier empresa tecnológica o proveedor de servicios críticos.

El documento subraya que los “vínculos críticos del Gobierno estadounidense con el sector privado” son indispensables para:

- vigilar amenazas persistentes contra redes estadounidenses,

- proteger infraestructuras críticas,

- realizar detección en tiempo real, atribución y respuesta,

- y articular tanto la defensa de red como las operaciones cibernéticas ofensivas.

Es decir, se da por hecho que las empresas de telecomunicaciones, cloud, energía, transporte, banca y grandes proveedores de software integrarán el dispositivo de seguridad nacional, de manera más o menos explícita.

Además, la estrategia vincula esta agenda cibernética a una política de desregulación selectiva: para mantener la competitividad y la capacidad de innovación, Washington busca eliminar obstáculos regulatorios en aquellos ámbitos donde considera que la regulación frena su ventaja tecnológica frente a países rivales.

Europe: A Wake-up Call on Technological Theft and Cyberespionage

Although the document’s focus is not primarily European in terms of technology, there is a section that directly concerns Brussels and euro capitals. In the part dedicated to Europe, it urges European countries to more firmly combat “excessive mercantilism, technological theft, and cyberespionage”, along with other practices considered economically hostile.

In sector-language, this means that the United States expects:

- closer coordination on exports controls of sensitive technology,

- a unified stance against digital espionage operations targeting companies and organizations,

- and a clearer alignment in defending intellectual property, industrial data, and trade secrets.

For Europe’s cloud, semiconductors, 5G/6G, AI, or cybersecurity industry, this serves as a reminder that strategic technological autonomy will depend not only on national programs but also on how relationships with Washington are managed and on which standards are adopted in the process.

AI as a Tool for Influence: From the Gulf to Tech Alliances

An striking example of technology used as diplomatic currency appears in the chapter on the Middle East. The Strategy mentions Trump’s visits to several Gulf countries in 2025 and states that he gained the support of these states for the “superior AI technology of the United States”, strengthening alliances.

The implicit message is that AI is not only seen as a productive or military tool but also as a foreign policy asset: a country wishing to integrate into the U.S. sphere can access:

- collaboration in AI,

- defense agreements,

- and access to capital markets and technology.

The text proposes replicating this logic with Europe, Asia, and allies like India, building coalitions that leverage the U.S.’s comparative advantage in finance and technology to open export markets and forge long-term alliances.

What the Tech Sector Faces in This New Phase

For a tech company, a data center, an AI startup, or a semiconductor supplier, this National Security Strategy sketches several scenarios:

- Increased pressure to choose sides on standards, supply chains, and critical infrastructure deployments.

- Greater influence of national security considerations in decisions previously seen as purely commercial: from where chips are manufactured to what technology is deployed in 5G networks or who maintains an AI system in production.

- More opportunities for those aligned with declared priorities (AI, quantum, autonomous systems, cybersecurity, infrastructure defense, semiconductors), but also more scrutiny.

- And, simultaneously, greater regulatory and geopolitical uncertainty for those operating across jurisdictions.

What has long been a mostly theoretical debate—“geopolitics of technology”—becomes now official policy of the world’s leading power.

For those wishing to delve into the tone and details of this shift, the complete full document in the PDF of the National Security Strategy of the United States of America, November 2025 is available, accompanying this information.

via: Noticias de Madrid