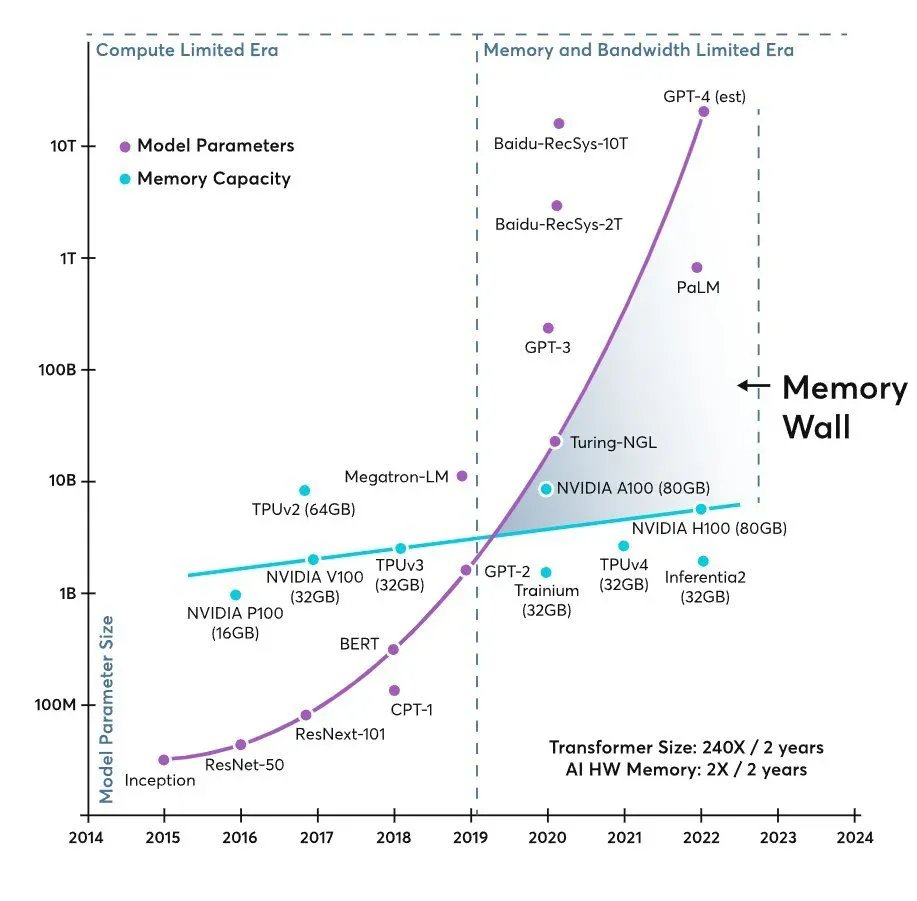

For years, the conversation about AI infrastructure has been explained with a simple idea: “GPU shortages.” But in 2026, the bottleneck starts to be described differently. A widely circulated graph among technical circles and investors shows two curves diverging like scissors: model sizes grow almost exponentially, while the available memory per accelerator advances at a much slower pace. The result is the same in any data center: if the GPU doesn’t receive data at the right speed, its power is underutilized—even if the hardware is cutting-edge.

This tension is summarized by a term increasingly appearing in academic papers and specialized blogs: “memory wall”. It’s not just about “lack of memory,” but about the set of capacity, bandwidth, and latency needed to transfer data between the compute logic and various memory levels (from on-chip caches to HBM or DRAM). In transformer-based models—especially during inference—memory and its bandwidth can become the dominant factor over pure computation, directly impacting cost, power consumption, and latency.

From the era of compute to the era of feeding the accelerator

The industry has experienced a similar situation with traditional computing: increasingly faster CPUs waiting for RAM to supply data. In AI, the scenario repeats but on an industrial scale. As models grow larger, so do the requirements for moving parameters, activations, embeddings, and—during inference—internal caches that maintain context. When that “data train” doesn’t arrive on time, the accelerator spends part of its cycle waiting.

In this context, investment is shifting: it’s no longer enough to install more GPUs; there must also be systems designed to keep them busy, with memory that’s closer, wider, and with more usable capacity. This is why technical discussions are filled with abbreviations that were almost invisible to the general public before: HBM, CXL, more complex memory hierarchies, and architectures trying to reduce “bytes moving” costs versus “operations.”

HBM and DDR5: memory returns to the center of design

High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) has become the symbol of this new stage because it addresses the most critical issues: bandwidth per watt and physical proximity to the chip. Memory manufacturers are positioning their most advanced lines as the “power supply” needed for training demanding models, reserving DDR5 for scalability and cost in more generalist setups. According to Micron Technology’s technical material, HBM3E and DDR5 are highlighted for training workloads, while expansion modules based on CXL are proposed as a way to extend capacity beyond direct channels when the “dataset or model size” becomes the bottleneck.

This strategy illustrates an increasingly accepted idea: the near future isn’t about choosing “a memory type,” but mixing layers (HBM for speed, DDR for volume, and CXL-like extensions to grow without rebuilding the entire platform). In real-world terms, this translates into racks with greater complexity and greater reliance on the supply chain of advanced memory components.

The other major player: flash for checkpoints and fast storage

The debate isn’t limited to HBM. Training flows and large model services depend on checkpoints, massive datasets, and quick local storage to avoid turning the cluster into a “wait-for-disk” machine. This is why the market is seeing increased traction for enterprise NAND and SSDs: not just for capacity, but for sustained performance and predictable latencies.

Leading this discussion, SanDisk has regained prominence after its corporate separation finalized on February 24, 2025, when it started operating as an independent company under the ticker SNDK. Financial media have linked recent revenue and profit growth to IA-driven demand and supply pressures, even mentioning multi-year contracts and firmer prices to guarantee supply.

For a tech-oriented audience, a pragmatic takeaway is clear: as models grow, the “backstage” of training and inference becomes more professionalized. AI doesn’t only reside in the chip; it extends through the entire pipeline—from ultra-high-speed memory to storage solutions hosting datasets, checkpoints, and deployment artifacts.

Micron, investments, and capacity: memory as an industrial bet

The pressure isn’t only reflected in product catalogs but also in large-scale investments. In January 2026, Reuters reported that Micron plans to invest $24 billion in a new manufacturing plant in Singapore to address the global memory shortage driven by AI applications and “data-centric” workloads. This same report highlighted that Singapore already hosts most of Micron’s flash production and that the company has an advanced HBM packaging plant there, valued at $7 billion, with contributions expected from 2027.

Apart from geographic details, the message is clear: memory is becoming a strategic component, not just an accessory. When industry enters this dynamic, it impacts everything: availability, prices, delivery times, and architectural decisions within data centers.

hyperscalers and the cost of keeping GPUs “hungry zero”

Major cloud operators—Google, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft—compete to train and serve increasingly demanding models. The usual narrative focuses on massive NVIDIA accelerator purchases, but the real challenge is sustaining a “factory” where chips are busy most of the time.

This analogy of the “memory wall” is a useful metaphor: on one side, the industry celebrates ever-growing models (including unofficial estimates attributed to OpenAI), and on the other, hardware needs more memory and bandwidth to make that size efficiently usable. If the system isn’t well fed, the solution isn’t always “buy more GPUs”—it can also mean increasing memory per accelerator, improving internal networking, and optimizing data flow.

The next wave: architecture, not just raw power

The most interesting shift in this phase is that innovation is moving toward system architecture: how parameters are distributed, cache management during inference, how to reduce memory traffic, and how to move less information for the same result. The memory wall isn’t broken with a single component but with an integrated set: more capable HBM, better interconnects, fast local storage, and designs embracing “data movement” as the new luxury.

In the short term, the most visible consequence will be: AI data centers will tend to be more expensive and complex but also better optimized. In this journey, memory—HBM and flash—ceases to be mere accessories and becomes the core factor determining whether a cluster performs at 30% or approaches its true potential.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly does “memory wall” mean in language models, and why does it impact inference so much?

The “memory wall” describes the point where performance is limited by memory capacity, latency, or bandwidth rather than computation. During inference, the need to maintain and move context data and internal structures can make memory the main bottleneck.

Is HBM3E essential, or is DDR5 still valid for AI workloads?

HBM3E is typically used when maximum bandwidth and energy efficiency are required for high-end training. DDR5 remains very useful for cost and scalability, particularly in setups where total capacity outweighs peak performance.

What role does flash storage (SSD/NVMe) play in AI data centers?

Flash is key for fast storage of datasets, checkpoints, and I/O-intensive operations. A slow storage subsystem can bottleneck training pipelines and deployment processes even with powerful GPUs.

How does CXL fit into the strategy to overcome memory limitations in AI servers?

CXL allows flexible expansion of memory capacity beyond traditional channels, providing a pathway to scale volume when the limiting factor is not just bandwidth but the total capacity needed for datasets and models.

via: X Twitter