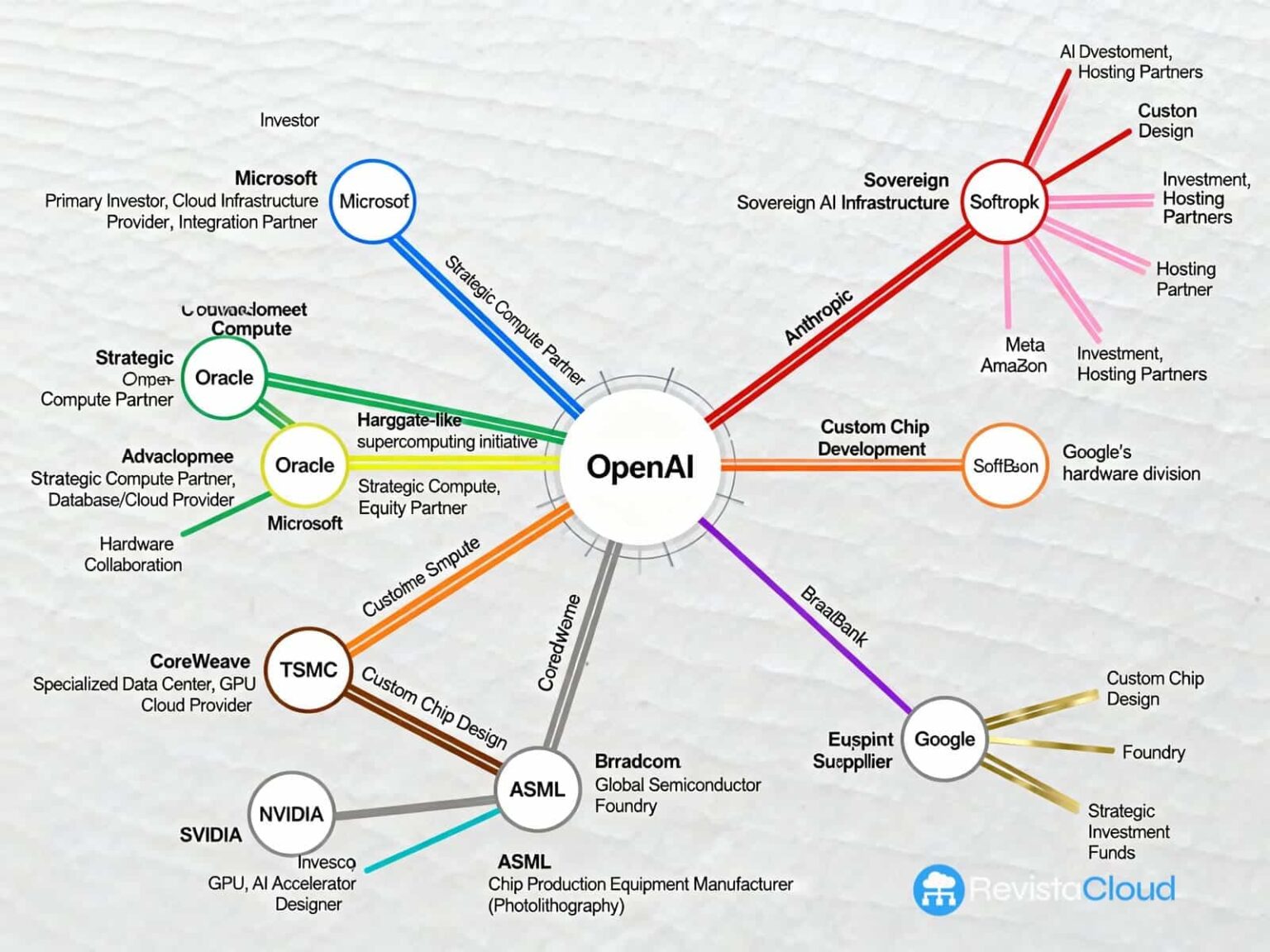

The chart published by the Financial Times on the OpenAI ecosystem has almost served as an X-ray of power in the AI era. It features interconnected names like Microsoft, NVIDIA, Google, Amazon, Meta, Oracle, SoftBank, Broadcom, and CoreWeave, connected by arrows representing cross-investments, computing contracts, data center agreements, and chip development.

What this map shows is simple to summarize but hard to accept: AI is no longer just another “sector” of the digital economy but a hyper-connected system where a few companies hold critical infrastructure for the rest of the world.

From Euphoria to Shared Risk

Over the past years, the market has applauded every AI-related announcement: new models, more computing power, major alliances. However, the recent mega-bets by Sam Altman and other sector leaders are no longer seen solely as growth promises but also as sources of fragility.

This vulnerability lies in the network of dependencies:

- OpenAI requires enormous amounts of NVIDIA GPUs and affordable electricity to train increasingly larger models.

- Microsoft provides cloud infrastructure and capital but depends on NVIDIA chip supplies and the capacity of its own data centers.

- Oracle, Amazon, Google, Meta, and newcomers like CoreWeave compete for the same scarce resource: energy and compute infrastructure at a planetary scale.

When all are tied to the same chip suppliers, energy contracts, and data center builders, each new expansion not only broadens business potential but also increases the risk that a failure propagates through the entire chain.

The parallels with finance are unavoidable: just as in 2008, when banks realized they shared too many hidden risks, the AI map suggests that an interruption in GPU supply, a serious regulatory problem, or an energy crisis could simultaneously impact a large part of the ecosystem.

Computing, Energy, and Debt: The New Triangle of Dependence

Enthusiasm for generative AI has driven big tech firms to announce hundreds of billions of dollars in infrastructure investments for this decade. Much of this spending is focused on three main areas:

- Computing: Massive acquisition of GPUs and specialized accelerators designed for AI by NVIDIA, AMD, or other manufacturers.

- Energy: Long-term contracts to ensure abundant, preferably renewable, electricity to meet the rising demand of data centers.

- Data centers and interconnection: Building hyperscale campuses and high-capacity fiber networks to move data and models across regions.

Adding to this is the financial component: corporate debt, external financing agreements, and public-private investment vehicles supporting the new wave of infrastructure. The result is that the same network promising to accelerate global productivity also concentrates economic, energy, and technological risks in very few nodes.

Europe: From Lost Industrial Power to Captive Client

If the AI map depicts a hyper-tied system dominated by U.S. players (and, to a lesser extent, Asian ones), Europe’s position appears on the margins.

The continent had a strong electronics industry for decades. Companies like Philips managed nearly the entire value chain, from components to consumer products. Today, that structure is fragmented or has disappeared.

ASML has become an indispensable global champion in lithography for advanced chips, but its business depends largely on non-European clients, and the continent lacks foundries capable of producing at the most cutting-edge nodes. The production of next-generation semiconductors is concentrated in Taiwan (TSMC) or South Korea (Samsung), under strong U.S. geopolitical influence.

The EU has responded with the Chips Act and more recently with proposals for a kind of “Chips Act 2.0.” However, European auditors have warned that official targets—like achieving a 20% global market share in chips by 2030—are unrealistic as currently planned due to a lack of financial coordination and industrial critical mass.

Meanwhile, much of the cloud and AI infrastructure used by European companies and public institutions runs on U.S.-based platforms: AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, or hybrid clouds tied to these providers. Europe consumes AI as a service rather than building its complete technological stack.

Talent and Ambition Gap

Europe’s industrial weakness is compounded by a human talent gap. While it trains top-tier researchers in machine learning, physics, or materials engineering, it struggles to retain many of those profiles in industrial projects of its own.

Where the U.S. and China are building companies capable of designing chips, full architectures, and global services, Europe boasts excellent labs and promising startups… which often end up being acquired or relying on external infrastructure to scale.

Without an advanced foundry, competitive GPU manufacturers, or an industrial ecosystem willing to take long-term risks, the continent risks remaining a client and regulator rather than a protagonist.

Is It Too Late to React?

The diagnosis is tough but not necessarily final. Precisely because AI is forcing a rethink of global infrastructure, a narrow but real window opens for Europe to rebuild some of its technological autonomy.

Some possible lines of action, already debated in Brussels and governments, include:

- Promoting sovereign data centers and supercomputing that prioritize renewable energy, heat reuse, and open access for universities, companies, and governments.

- Supporting open hardware, such as RISC-V architectures or Europe-designed accelerators for specific tasks (edge AI, post-quantum cryptography, scientific simulation).

- Creating public-private consortia involving universities, SMEs, and large industrial players to design and operate foundation models hosted on European infrastructure.

- Reorienting the Chips Act from market share goals to ensuring critical technologies: advanced packaging, low-power AI nodes, components for quantum communications, etc.

Spain, with its competitive renewable energy, strategic location, and growing data center ecosystem, could play a significant role in this new phase if it implements a coordinated strategy—from stable energy policies to incentives that attract supercomputing projects, private clouds, and emerging hardware manufacturers.

The True Turning Point

The Financial Times graphic not only shows who currently leads the AI race but also what kind of system is being built: one where computing, energy, funding, and data are so concentrated that a failure in one part can shake the entire ecosystem.

The key question is no longer which language model will be most powerful in two years but who will control the infrastructure making them possible and how power will be distributed when governments, companies, and citizens depend on the same systemic risks.

If Europe remains a consumer of external AI services, it will assume that risk without real influence. However, if it invests in more open architectures, sovereign infrastructure, and an ambitious industrial policy, it can still gain some autonomy in a game that today seems decided… but is not entirely over.

Sources:

Financial Times, Citi Research; public reports on the OpenAI ecosystem and partners.

Documentation on the Stargate project and the computational and energy needs of the new wave of generative AI.

Reports and news on the European semiconductor strategy (EU Chips Act and proposed “Chips Act 2.0”) and its evaluation by the European Court of Auditors.