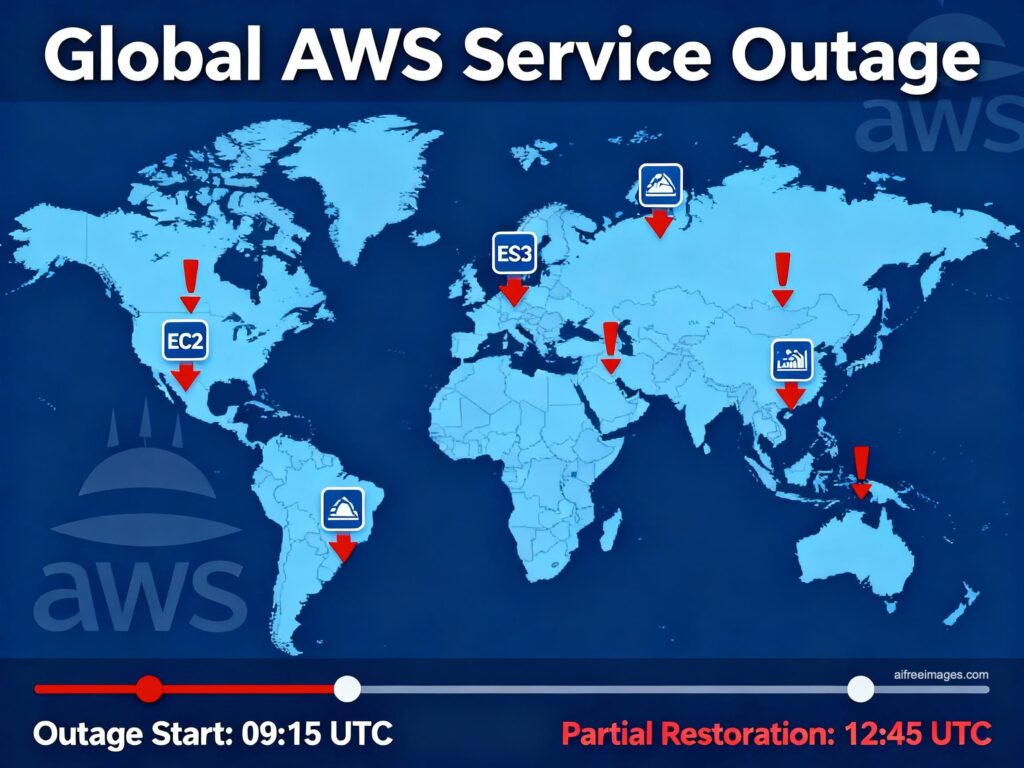

The global outage of Amazon Web Services (AWS) on Monday, October 20th, reminded us once again of how fragile the digital fabric can be when too many components depend on a single point. In Spain, a diverse range of services such as Bizum, Ticketmaster, Canva, Alexa, and several online games experienced errors or remained inaccessible for hours. The epicenter was in US-EAST-1 (N. Virginia): a DNS issue toward DynamoDB caused failures in EC2, Lambda, and load balancers, triggering a domino effect on dozens of services.

Beyond the specific incident, the situation sends an uncomfortable message: we continue to concentrate risks in the same region of the same hyperscaler, and Europe lacks planned alternatives when the giant stumbles. “Many companies in Spain and Europe rely entirely on American providers and don’t have a backup plan even when their services are critical,” summarizes David Carrero, cofounder of Stackscale (Grupo Aire). “It’s good to aim for high availability (HA), but if everything depends on some common element, HA will fail.”

What happened (and why we noticed it here)

- Trigger: DNS resolution failures for DynamoDB in US-EAST-1.

- Cascade: errors when launching EC2 instances, issues with Network Load Balancer, Lambda invocations, plus queues and throttling in dependent services.

- Impact in Europe: despite many loads being in European regions, global control planes and internal dependencies (identity, queues, orchestration) anchor in N. Virginia, resulting in failed logins, 5xx errors, and latency issues in Spain.

“We see this repeatedly because the architecture isn’t truly multi-region,” adds Carrero. “Control planes in a single region, centralized data for convenience, and failovers that are not rehearsed. When a major stumble happens, everything stops.”

Technical lessons from the incident

- US-EAST-1 can’t be an ‘all-in-one’: it’s convenient and cheap, but it concentrates systemic risk.

- Multi-AZ doesn’t equal resilience: if a cross-cutting component (like a service’s DNS) fails, all zones suffer.

- The backup plan must be tested: a runbook without periodic gamedays is worthless.

- Observability and DNS matter: if your monitoring and identity control depend on the affected region, you’re left blind precisely when you need visibility.

- Communication: clear, frequent updates reduce uncertainty and support costs.

What should change in cloud-first architectures?

1) Truly multi-region

Separate control/data planes and test failover procedures. “Not everything needs active-active, but the critical systems do,” notes Carrero. “Identify which service cannot go down and design for that RTO/RPO, not the other way around.”

2) DNS/CDN with failover capabilities

Implement failover policies in DNS/GTM based on service health, and use alternative origins in CDN. Avoid implicit anchors to a single region.

3) Timed backups and restoration tests

Create immutable / offline backups and regularly test restoration in real-time scenarios. A backup exists only when restored.

4) Manage global dependencies

Identify “global” services anchored in US-EAST-1 (like IAM, queues, catalogs, global tables) and prepare alternative routes or mitigations.

5) Multicloud… when it makes sense

For continuity, sovereignty, or regulatory risk, use dual providers at the minimum viable: identity/registry, backups, DNS, or a critical subset. “It’s not about abandoning hyperscalers,” clarifies Carrero, “but about reducing risk concentration and gaining resilience.”

Europe has options: complement them

The other side of the debate is industrial. “In Europe, there are many winning options that are sometimes due to pressure to ‘stick with the giants’,” points out Carrero. “Not only Stackscale can be an alternative or complement: the European and Spanish ecosystem—private cloud, bare-metal, housing, connectivity, backup, and managed services—is broad and professional, without any envy of the hyperscalers for most needs.”

Practically speaking:

- Locate critical data and apps in European infrastructure (private/sovereign) and connect with SaaS/hyperscalers where value is added.

- Ensure that continuity layers (backups, DNS, observability) do not share failure domain with the primary provider.

- Rely on local partners for real SLAs and proximate support.

What to do today (and be ready for next Monday)

Users

- Check the service status page of the impacted service before reinstalling.

- Retry later: recoveries are gradual.

IT teams (now)

- Avoid rash changes; switch only if a proven route exists.

- Communicate status and next steps; gather metrics for the post-mortem.

IT teams (next weeks)

- Map RTO/RPO per service and adjust architecture/budget accordingly.

- Practice failover procedures (gamedays) and document results.

- Externalize observability/emergency identity outside the main failure domain.

- Decouple global dependencies; review potential breakpoints if US-EAST-1 stops responding.

The core issue: dependence and autonomy

The outage was resolved within hours, but the pattern repeats (2020, 2021, 2023, and now 2025). The lesson isn’t “avoid the cloud,” but design for failure and diversify. “Resilience isn’t just a slogan,” Carrero concludes. “It’s engineering and discipline. If your business relies on your platform, it must continue even if the primary provider fails. HA isn’t backup; the backup is another complete route to achieve the same outcome.”

In summary: in Spain and Europe, we still lack a backup plan when a hyperscaler sneezes. It’s time to redistribute load, test continuity, and activate the European muscle as a complement. The next incident isn’t a remote possibility; it’s when. The difference between a scare and a crisis will once again be the preparation.