When someone says “I’m out of memory,” they usually mean RAM. However, the memory of a modern system is an ecosystem: multiple different technologies stacked in a hierarchy to balance speed, cost, power consumption, and persistence. The simple reason is: there is no memory that is lightning-fast, inexpensive, huge, and capable of retaining data without power all at once.

This “layer of memories” is what allows a CPU not to spend half the day waiting for data (the famous memory wall), enables a server to handle thousands of web requests smoothly, or allows your laptop to always boot with the correct firmware even when the battery is dead.

Below is a clear (and useful) guide to understanding the four major families that appear constantly in PCs, mobiles, and data centers: ROM, DRAM, SRAM, and flash memory.

1) First things first: volatile vs. non-volatile

The most important distinction is:

- Volatile memory: needs power to retain data. If it’s turned off, data is lost. Here lie DRAM and SRAM.

- Non-volatile memory: retains data without power. Here are ROM (broadly speaking) and flash.

With this in mind, it’s easy to understand why an operating system loads from a SSD (flash) into RAM (DRAM), and why the CPU has ultra-fast caches (SRAM).

2) ROM: the “boot” memory and its family of variants

ROM was born as “read-only memory,” but today the term is more broadly used to refer to firmware and low-level non-volatile storage: BIOS/UEFI, microcode, embedded controllers, etc.

Within this family, there are classic distinctions:

- Mask ROM: burned into the chip during manufacturing, immutable.

- PROM: programmed once after production.

- EPROM: erased with ultraviolet light (the classic “window” open to the chip).

- EEPROM: electrically erasable and reprogrammable (often byte by byte), widely used for configurations and firmware.

In real-world applications, much of modern firmware resides on specialized flash memories, but the concept remains the same: a reliable non-volatile medium to boot and control the system.

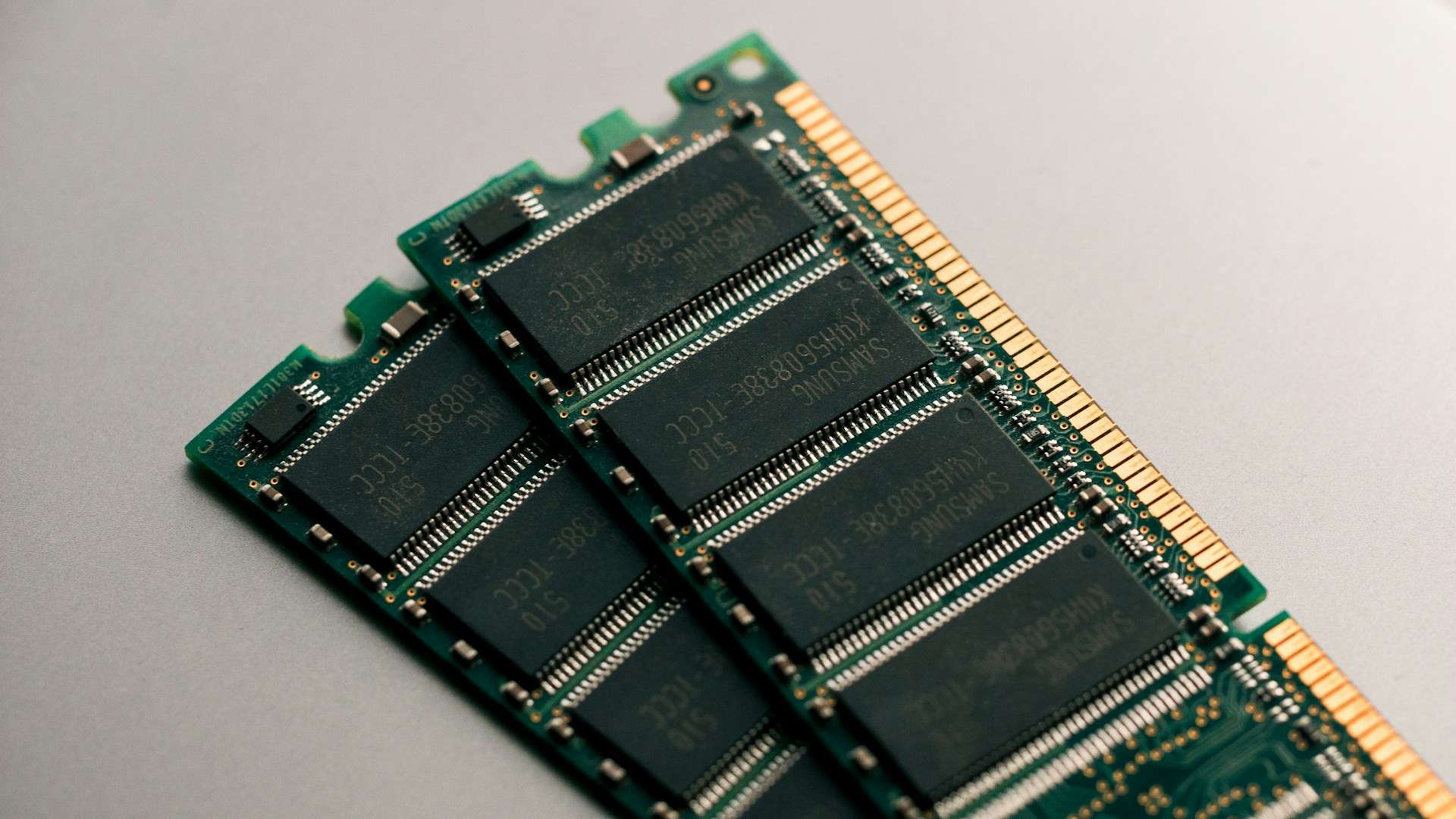

3) DRAM: the “real” RAM (and why it needs refresh cycles)

DRAM (Dynamic RAM) is the dominant main memory in PCs, servers, and many devices. It stores each bit using a very dense combination of capacitor + transistor. This makes it relatively inexpensive per GB…but with a drawback: the capacitor loses charge over time and needs to be refreshed periodically to keep data intact.

DDR, LPDDR, GDDR, HBM: same base, different goals

Practically all modern DRAM is SDRAM (synchronized to a clock), presented in “flavors” tailored to specific uses:

- DDR: typical desktop/server RAM (DIMMs).

- LPDDR: optimized for low power (thin laptops and mobiles, usually soldered).

- GDDR: designed for graphics cards (high bandwidth, more heat/power).

- HBM: stacked DRAM (2.5D/3D) for extreme bandwidth in AI/HPC applications.

Why “timings” matter

When you see numbers like CL30 or 30-36-36-76, you’re looking at latencies measured in clock cycles: the time DRAM takes to open a row, access a column, and deliver data. That’s why two kits with “many MHz” can perform differently depending on their actual latency.

4) SRAM: expensive, small…but essential

SRAM (Static RAM) does not use capacitors: it uses bistable cells (typically 6 transistors per bit) that maintain their state as long as power is supplied, without refresh cycles. The result: very low latency and highly predictable behavior.

Why don’t we have 512 GB of SRAM? Because it’s very costly and low density. Its natural roles include:

- CPU and GPU caches (L1/L2/L3)

- high-performance buffers

- network devices and systems where deterministic response matters

In actual performance scenarios (including web servers), these caches drastically influence the perceived speed: they prevent constant trips to DRAM.

5) Flash: the modern storage (SSD, mobile, USB) with NOR and NAND

Flash memory is non-volatile and dominates current storage: SSDs, mobile devices, SD cards. It’s based on floating-gate transistors (or related technologies) that hold charge to represent bits.

Historically, Fujio Masuoka (Toshiba) is credited with inventing flash in the 1980s—a key milestone that allowed solid storage to scale in capacity and affordability.

NOR vs NAND

- NOR flash: favors random access and, in some scenarios, allows execute-in-place (running code directly from flash), which is why it’s used in firmware and embedded systems.

- NAND flash: favors density and page/block operations; it’s the foundation of modern SSDs and mass storage. It requires controllers with ECC, wear leveling, bad block management, etc.

SLC, MLC, TLC, QLC (and why your SSD might be “failing”)

In NAND, each cell can store 1, 2, 3, or 4 bits (SLC/MLC/TLC/QLC). More bits per cell mean higher capacity and lower cost… but often reduced endurance and sustained performance, plus increased controller complexity.

6) How all this relates to servers (and WordPress)

Although WordPress is “just PHP and MySQL,” the physics underneath matter:

- SRAM (caches): if the access pattern is efficient, the CPU works “nearby” and responds quickly.

- DRAM (server RAM): here live object caches, system buffers, hot database data. If RAM is lacking, the I/O bottleneck appears.

- Flash (NVMe/SSD): it’s fast but not equivalent to RAM; heavy random writes or a nearly full SSD can reduce sustained performance (noticeable as latency spikes).

- ROM/firmware: may seem invisible… until something goes wrong (microcode, compatibility, boot issues, platform patches).

Understanding this hierarchy helps with better diagnosis: not everything is fixed by “adding more RAM” if the bottleneck is storage, caches, latency, or access patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which memory makes a PC “fast”: RAM or SSD?

Both, but for different reasons: SSD speeds up loading and access to persistent data; RAM accelerates active system operations. The feeling of fluidity depends heavily on having enough RAM and good sustained SSD performance.

Why does DRAM need refresh cycles while SRAM does not?

Because DRAM stores bits as charge in a capacitor that leaks over time; SRAM uses a flip-flop circuit that maintains its state as long as power is supplied, with no refresh required.

Which is better for storage: TLC or QLC?

It depends on your workload. For mostly read-heavy tasks and cost/benefit, QLC may suffice. For intense writes and sustained performance, TLC (or solutions with better overprovisioning and controllers) tend to be more reliable.

Does ROM still exist now that everything seems “upgradable”?

Yes: firmware and boot processes still rely on reliable non-volatile memory. What’s changed is that much of today’s “ROM” is reprogrammable (EEPROM/flash), but its fundamental role remains.

via: wccftech