While half the world accelerates in artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and energy transition, Spain faces a much simpler problem: fewer and fewer people are willing to study Engineering… and too many abandon it along the way.

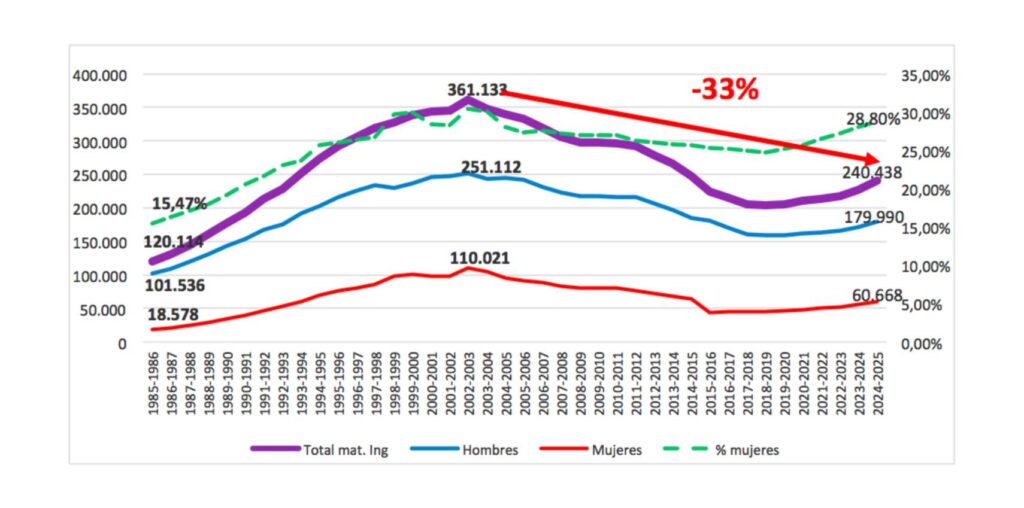

According to the report Analysis of University Studies in Engineering 2025, prepared by the Institute of Engineering Graduates and Technical Engineers of Spain (INGITE) and the College of Technical Civil Engineers, engineering enrollments have fallen by 33% since the 2002-2003 academic year. Today, students in these programs only represent 16.98% of the total university population, just two points higher than in the mid-1980s, when the economy and job market were drastically different.

Meanwhile, the actual dropout rate in these programs hovers around 50%. And those who manage to finish on time and with all courses passed account for barely 7.54% of total enrollments. A slow but steady drip of talent that the Spanish tech sector is already starting to feel impact from.

Fewer vocations, more dropouts, and degrees that don’t qualify

The INGITE report quantifies a feeling shared for years by companies and universities: engineering has lost its appeal among young people.

On one hand, there’s a structural decline in new students choosing engineering. The newer generations increasingly opt for other fields of study, even in technological areas with less “hard” labels: degrees related to design, digital communication, business, or scientific-health branches.

On the other hand, the funnel narrows within technical schools:

- Nearly half of students drop out before graduating;

- Only a small fraction complete the curriculum on schedule;

- And a significant portion of those who start realize too late that the career doesn’t match their expectations or their level of preparation.

Additionally, a phenomenon particularly concerning the professional sector is: 53% of engineering degrees do not grant professional qualifications. In other words, they do not directly enable graduates to practice as licensed engineers in regulated professions. INGITE warns that this proliferation of “non-qualifying” titles, often disconnected from real needs of the productive system, causes confusion among students and undermines guarantees for companies and administrations that require clearly accredited profiles.

A technological problem, not just academic

From an external perspective, it might seem like an internal university debate. But, for a tech-focused outlet, the angle is different: without enough engineers, the digital production model simply doesn’t fit.

The decline in enrollments and high attrition affect several key fronts:

- Digital infrastructure and cloud: data centers, telecom networks, cloud service platforms, or 5G deployment require telecommunications, industrial, computer, and other engineers capable of designing, operating, and maintaining increasingly complex systems.

- Artificial intelligence and data: beyond media hype, serious AI projects need individuals with solid foundations in mathematics, computing, electronics, or automation. It’s not enough to “use models”: you must know how to integrate them into processes, infrastructures, and products.

- Energy transition and networks: renewable energy integration, electric vehicles, energy storage, and smart grids depend on electrical, energy, civil, and industrial engineers skilled in planning and executing large infrastructure projects.

- Cybersecurity and technological sovereignty: without a critical mass of systems, software, telecommunications, and hardware engineers, discussions about digital sovereignty, post-quantum cryptography, critical infrastructure protection, or chip design are left to other countries.

The connection is direct: fewer engineers means less capacity to innovate, automate, deploy infrastructure, and compete. A country with a structural deficit of technical profiles is condemned to import technology, services, and decisions.

An education system that arrives late to the game

The report and sector voices agree: it’s not just a “talent gap,” but a system misaligned with what is later required from young people.

1. Orientation comes too late

Educational research has pointed out for years that interest—or rejection—of STEM fields forms very early. Vocational preferences begin to take shape in primary school and consolidate during secondary education. Yet, many students receive realistic information about what engineering entails only in second year of Bachillerato, when they are deciding on admissions exams (EBAU), cutoff scores, and university choices.

The result is hundreds of young people dismiss these careers based on vague ideas (“it’s just math,” “no social life,” “I don’t see myself capable”) without having concrete experiences: visits to tech companies, experimental projects, contacts with role models, or understanding what an engineer or IT professional does daily.

For the tech ecosystem, this means losing potential vocations years before they reach university.

2. Universities that don’t clarify the “why”

In many schools, even prestigious ones, the first contact with engineering still involves a mix of mathematical analysis, physics, basic programming, and circuit theory. All essential, but often presented in isolation, with little explicit connection to real-world problems.

Tech companies have been calling for a shift: real projects starting from first year, challenges posed by companies, prototyping in labs, teamwork, and small incursions into applied research. Not just as capstones but as the guiding thread throughout training.

When students see that what they learn helps develop an algorithm that truly runs on a server, a control system that governs a robotic arm, or a model that optimizes energy consumption in a building, their perception changes. Engineering stops being just formulas and becomes a toolbox with impact.

3. Unbalanced expectations: easy school, tough degree

The third recurring issue in conversations between educators and industry is: the gap between the level of school and that of technical degrees.

Engineerings demand hours of study, deep focus, and resilience to frustration. If the previous educational system has reduced content, eased assessments, or cut back on science without offering equally demanding alternatives, the leap to university is brutal. Students arriving without solid study habits or experience tackling complex problems often think, “this isn’t for me,” when the real issue is a lack of proper preparation.

For the tech sector, this gap translates into fewer students daring to pursue demanding degrees and more young people abandoning them at the first tough subject.

4. A social narrative that deters rather than attracts

Finally, the “story” surrounding engineering matters: the most repeated phrase isn’t “it’s a strategic career,” but “it’s a very hard degree.” More talk about sleepless nights than about designing photovoltaic parks, fiber optic networks, clinical AI systems, or high-speed rail lines.

This narrative, repeated for years in families, media, and even within educational centers, pushes many young people toward easier routes, even though their career opportunities and salaries may differ significantly later.

If Spain aims for an economy based on data, automation, clean industry, data centers, and advanced digital services, the message should change to a much simpler one: without engineers, there’s no technological sovereignty, energy transition, or smart digitalization.

What could the tech ecosystem do… besides lament?

The diagnosis is on the table. The question is: what can Spain’s tech environment concretely do?

- Engage in classrooms: software companies, data centers, telcos, equipment manufacturers, or startups can collaborate with schools and institutes to showcase real case studies, not just at fairs but through stable programs.

- Strengthen ties with engineering faculties: design practical courses, fund projects, open data and real problems for final projects, offer technical mentorships. It’s not just about sponsorship but about integrating industry realities into curricula.

- Support scholarships and bridging programs: especially for students from backgrounds with less university tradition or fewer resources, where transitioning into engineering appears riskier.

- Contribute to changing the narrative: highlight diverse profiles of engineers, tell impact stories, and show that behind every app, network, renewable plant, or AI model, there are people who studied degrees many now avoid.

The 33% drop in engineering enrollments is not just a statistic; it’s a warning sign for any country that wants to keep talking seriously about Industry 4.0, AI, 5G, cloud, or cybersecurity. The time to reverse this trend is not infinite… but it’s not exhausted yet.

Reference: The Objective: Young people don’t want to be engineers: enrollments plummet 33% in 20 years. and Madrid News