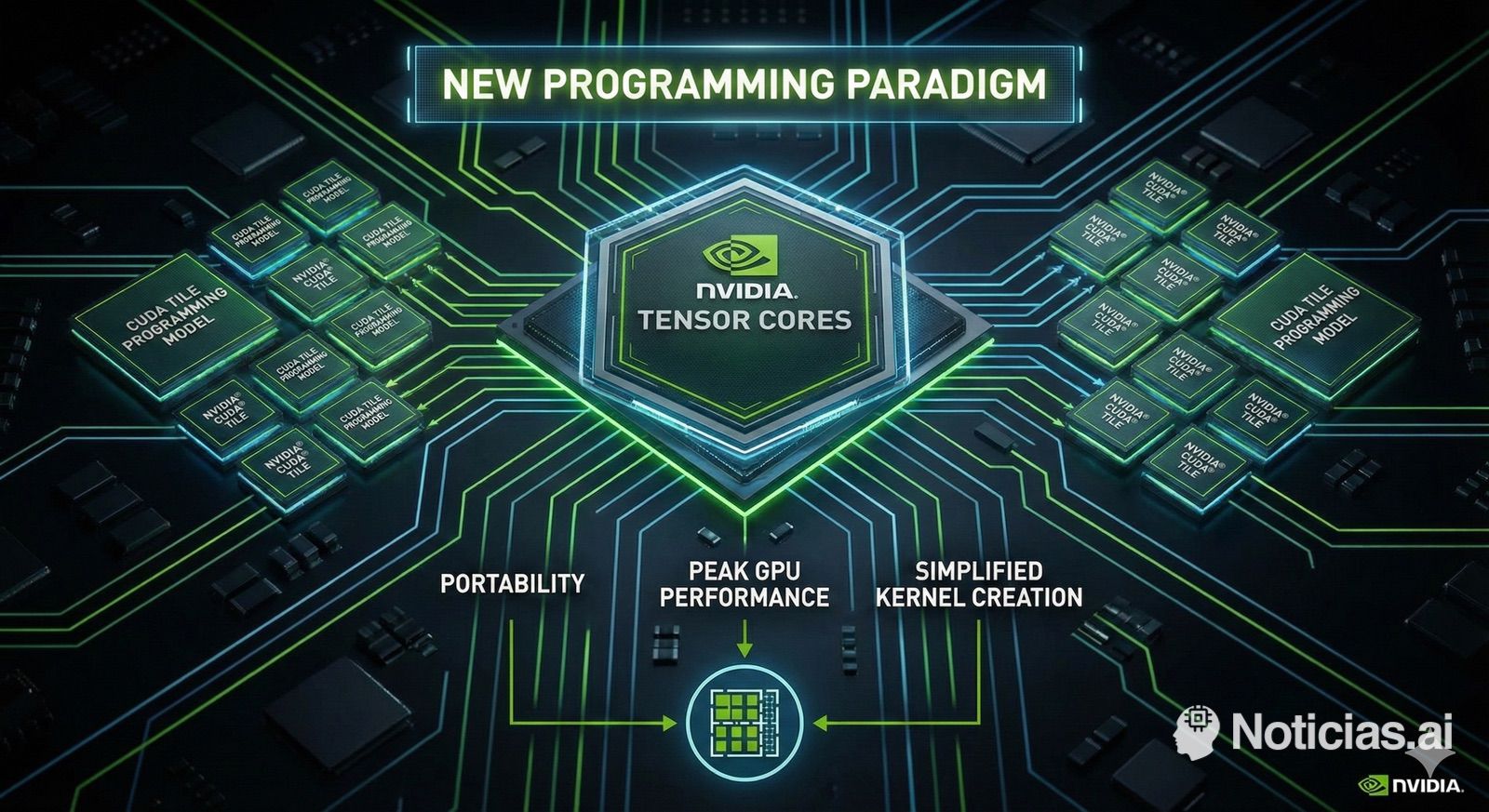

NVIDIA has decided to take a step in the only area where it still had room to differentiate itself from competitors: software. With the release of CUDA 13.1 and the introduction of CUDA Tile, the company makes the most significant conceptual shift in its GPU programming model since 2006, when it launched the first version of CUDA.

The underlying message is clear: after nearly 20 years of fine-tuning kernels at the thread, block, and shared memory level, NVIDIA wants developers to stop focusing so much on hardware and instead concentrate on the algorithm. The near future, if this approach succeeds, will revolve around programming “tiles” instead of individual threads.

From Threads and Warps to Tiles: A Shift in Mental Model

Until now, programming in CUDA meant controlling quite detailed aspects like:

- The distribution of threads and blocks.

- The hierarchy of memories (global, shared, registers).

- Synchronizations within a block and often architecture-specific intrinsics.

This approach allowed maximizing GPU utilization but had a downside: code heavily tied to microarchitecture and a steep learning curve. Tuning a kernel for a Volta, Ampere, or Hopper GPU wasn’t exactly the same, and teams with more low-level expertise held an advantage.

CUDA Tile aims to break this pattern. Instead of reasoning about thousands of independent threads, the developer works with tiles, i.e., logical fragments of data on which high-level operations are defined. The compiler and runtime then handle translating this work into specific instructions and deciding which chip units are used at each moment.

What is CUDA Tile and Why Does It Matter

NVIDIA describes CUDA Tile as a tile-based programming model oriented around Tensor Cores and designed for cross-generation GPU portability. The core technology of the system is Tile IR, an Intermediate Representation that acts as a virtual language between the developer’s code and the actual hardware.

Based on Tile IR is cuTile, the first implementation accessible to programmers. Currently, cuTile is available in Python, with plans announced to extend the same model to C++. The idea is that an engineer can write high-performance kernels using familiar Python syntax, defining operations on tiles instead of manually managing threads and blocks.

In practice, this means that:

- The programmer defines what calculations are performed on which data fragments.

- The compiler decides how to distribute those tiles among Tensor Cores, traditional calculation units, or specialized engines like TMA.

- The same kernel should run unchanged across different GPU generations, with automatic improvements when migrating to newer hardware.

In a way, this is the computing equivalent of what high-level graphics APIs did in their time: the developer stops interacting directly with the “metal” and delegates part of the optimization to the compiler.

Blackwell as the First Testing Ground

Although NVIDIA doesn’t limit CUDA Tile to a single family, the company designed Blackwell and Blackwell Ultra from the ground up with this programming model in mind. The new architectures include Tensor Cores and data paths optimized for working with tiles, enabling the runtime to:

- Decide which tiles to execute on internal accelerators.

- Manage the memory hierarchy (L2, HBM memory, registers) more intelligently.

- Minimize latencies and maximize the use of specialized units without requiring the developer to micro-optimize each kernel.

The key point is that, following the philosophy of CUDA Tile, the dependency shifts from the programmer to the compiler. Each new GPU generation can add instructions or internal engines, and the backend of Tile IR learns to utilize them. In theory, the source code remains stable.

Advantages for AI and Scientific Computing Teams

For teams developing AI models, scientific simulations, or high-performance computing applications, this move brings several practical benefits:

- Less hardware-specific code

Traditional optimizations—like micro-managing shared memory banks or manually designing access patterns—can be replaced by higher-level constructs based on tiles. - Faster development cycles

With cuTile in Python, complex kernel prototypes can be written and tuned more quickly. The jump from a Jupyter notebook to an optimized kernel is shortened. - Cross-generation portability

Moving from one GPU to another no longer requires rewriting large parts of the code. The focus shifts to the quality of the algorithm and tile tuning, not the internal architecture of each chip. - More uniform performance

Working with coherent data blocks allows the compiler to better organize data flow, reducing erratic behaviors and unexpected bottlenecks.

A Strategic Move in the “Ecosystem War”

Beyond the technical aspects, CUDA Tile reinforces NVIDIA’s almost unassailable dominance in the software ecosystem. While other players focus on alternatives like ROCm, SYCL, oneAPI, or open frameworks, NVIDIA consolidates an environment where:

- The hardware, compiler, libraries, and development tools are deeply integrated.

- Code written today in CUDA is highly likely to work—and perform better—in 5 or 10 years with new GPUs.

- Team productivity benefits from mature tools, extensive documentation, and a massive community.

For China and Europe, aiming to build independent ecosystems for reasons of technological sovereignty, this move presents an additional challenge. It’s not enough to produce powerful chips: they must also match—or at least come close to—the almost two decades of CUDA investment advantage and now, a paradigm shift that pushes the bar higher again.

Remaining Questions

Despite the excitement, some open questions remain:

- Adoption curve: teams with large CUDA “legacy” codebases will need to decide when and how to start migrating parts to CUDA Tile.

- Control level: there will always be extreme applications requiring low-level control. NVIDIA will have to balance what it exposes and what it abstracts.

- Vendor lock-in: as the model becomes more powerful and convenient, justifying migration to other platforms becomes harder—particularly concerning in the context of sovereign clouds.

What is clear is that the company has set the course for the next decade of GPU programming, playing on its strongest terrain: aggressive hardware combined with software that leverages every transistor.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between classic CUDA and CUDA Tile?

Classic CUDA requires explicit management of threads, blocks, and shared memory. CUDA Tile enables defining operations on high-level data tiles; the compiler determines how these tiles map onto hardware.

Do developers need to rewrite all their existing CUDA code?

No. CUDA Tile is introduced as a complementary model. Existing code continues to work, but new applications—especially in AI—can benefit from writing kernels directly with tiles and cuTile.

Is CUDA Tile only compatible with Blackwell GPUs?

Blackwell and Blackwell Ultra are the first architectures designed from the ground up with this model in mind, but NVIDIA’s declared intention is to extend compatibility to future generations and, likely, parts of the existing hardware when feasible.

What does this mean for competition and technological sovereignty?

The more advanced and productive the CUDA ecosystem is, the greater the dependency on NVIDIA’s GPU-based AI infrastructure. For regions seeking independent ecosystems, the bar for tools, performance, and stability rises once again.

Source: Nvidia CUDA Tile