In the race to build increasingly larger artificial intelligence systems, it’s not just about having more GPUs. You also need to move data within the rack at incredible speeds and with very low latency. That’s where traditional links start to squeak: copper becomes thicker, shorter, and harder to power; and optics, although promising, don’t always fit in cost and complexity when the goal is to connect equipment just a few meters apart.

In this context, proposals that, just a few years ago, sounded like science fiction have emerged: wireless interconnections within data centers, using millimeter-wave and terahertz frequencies and guiding signals through waveguides instead of traditional cables. Two leading names in this approach, according to IEEE Spectrum, are Point2 and AttoTude.

The bottleneck of AI racks: when copper runs “out of margin”

AI systems at rack scale not only train and run models; they also exchange states, activations, caches, and data between accelerators, CPUs, and internal networks. As bandwidth per link increases, copper faces well-known physical limits: losses, interference, and effects that force you to “pay” in performance with more material, higher power consumption, and less useful distance. Meanwhile, optical solutions can address part of the problem but also involve modules, photonics, and costs that are not always justifiable for short two-to-few-meter links, especially when the goal is to maximize density and energy efficiency inside the rack.

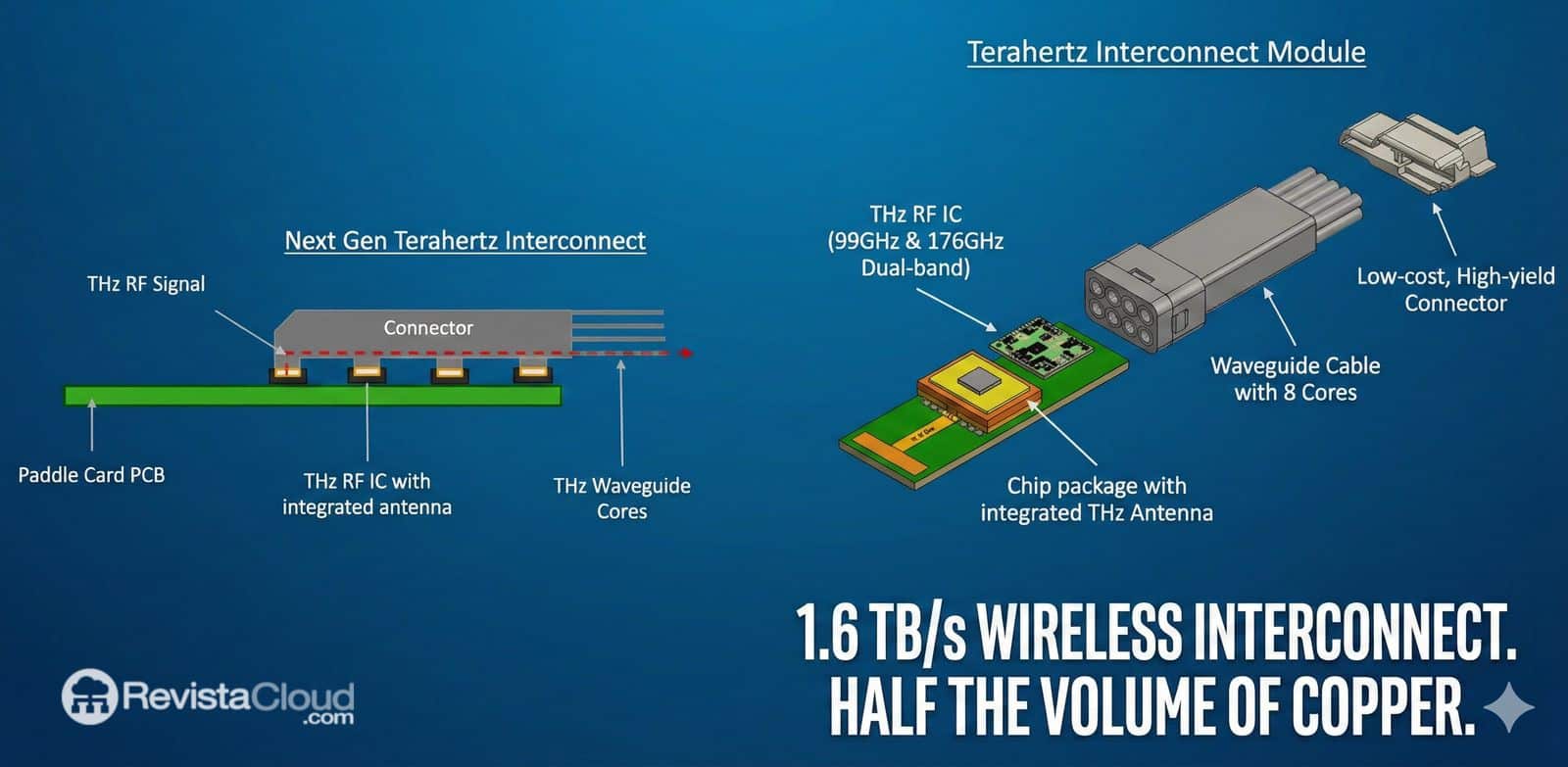

Point2: “cables” that are actually waveguides with built-in radio

Point2 describes its approach as an “active radio cable” based on eight waveguides called e-Tube. The idea is straightforward: each end of the “cable” has a pluggable module that converts digital signals into modulated radio signals (and vice versa), transmitting through the waveguide.

According to information published by IEEE Spectrum, each waveguide carries data using two frequencies (90 GHz and 225 GHz), and the entire set could reach 1.6 Tb/s with an approximate thickness of 8.1 mm, occupying around half the volume of a comparable active copper cable. Additionally, the company mentions ranges of up to 7 meters, sufficient for intra-rack or between-neighboring-rack connections.

An important detail to avoid another classic confusion: Tb/s (terabits per second) is not the same as TB/s (terabytes per second). Practically, 1.6 Tb/s equals about 0.2 TB/s, or roughly 200 GB/s (decimal). This distinction matters because headlines and discussions often mix bits and bytes, and the difference is a factor of 8.

Point2 also emphasizes two “industrial” points: their transceivers could be produced using known processes (IEEE Spectrum mentions a demonstration with a 28 nm chip alongside KAIST), and partners such as Molex and Foxconn Interconnect Technology have demonstrated the feasibility of manufacturing these assemblies without the need to reinvent factories from scratch.

AttoTude: moving into terahertz to increase reach and density

AttoTude pursues a similar goal but at even higher frequencies: between 300 and 3,000 GHz. Instead of a conventional “cable,” its approach uses a narrow dielectric waveguide (the publication describes the evolution from hollow copper tubes to very fine fiber-like guides) to minimize losses at those frequencies.

IEEE Spectrum reports that the company has demonstrated 224 Gb/s at 970 GHz over 4 meters, with projected viable reachs of about 20 meters. While it’s not (yet) a complete substitute for all data center links, this shows a clear direction for some players when copper becomes unscalable and optics aren’t always the “default” solution.

AttoTude is also raising capital to accelerate industrialization of its approach, according to corporate statements and specialized financial press.

Why “waveguides” instead of cables: at certain frequencies, cables fail

A core idea behind both proposals is that, as the link moves into the terabit territory, the “trick” of copper becomes costly: maintaining the signal requires shortening distances or thickening conductors, reducing density and increasing power consumption. Conversely, waveguides are a classic micro-technology: not exotic by definition, but a sensible way to confine and transmit radio signals at frequencies where other mediums become inefficient.

What they promise… and what remains to be demonstrated

It’s helpful to separate three levels of understanding:

- Proven results: laboratory figures or prototypes (such as AttoTude’s 224 Gb/s at 970 GHz) and technical descriptions (frequencies, waveguides, modules).

- Claimed advantages: Point2 asserts its solution can consume less energy than optical links, cost less, and add very little latency; these claims usually need validation in real deployments and independent comparisons.

- What data centers decide: integration with standard connectors, reliability, ease of maintenance, compatibility with topologies, and especially, scalability. Many promising technologies confront the realities of operational deployment here.

Quick comparison: two “radio within the rack” approaches

| Proposal | Frequencies Cited | Capacity Cited | Range Cited | Key Idea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point2 (e-Tube / active radio cable) | 90 GHz and 225 GHz | 1.6 Tb/s | up to 7 m | Waveguides + modules at ends converting digital ↔ modulated radio |

| AttoTude (terahertz) | 300–3,000 GHz (carriers) / demo at 970 GHz | 224 Gb/s (demo) | 4 m (demo) / ~20 m (projection) | Terahertz on dielectric waveguides for ultra-dense links |

What to watch in 2026 if this trend takes off

If these radio interconnections are to establish a foothold, three clear signals will emerge:

- Standardization and integration with “plug-and-play” formats and real rack ecosystems (not just demos).

- Scalability testing: sustained performance, tolerance to temperature, vibration, maintenance, and failure rates.

- Overall economics: cost per link and per rack, power use and cooling, and comparisons with optics/copper in specific scenarios (short distances, high density, low latency).

If the ultimate goal of AI is to scale “frictionlessly” within the rack, the battle isn’t only in the GPU but also in what connects each piece of the system.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why talk about Tb/s instead of TB/s in these interconnections?

Because network and interconnect specifications typically use bits per second (Tb/s). To convert to bytes, divide by 8: 1.6 Tb/s ≈ 0.2 TB/s (200 GB/s).

Can the “radio” inside the data center interfere with other equipment?

These proposals don’t aim to emit freely like Wi-Fi but rather guide signals through waveguides with modules at the ends. The key concern is signal integrity and isolation within the physical rack environment, which must be validated in real deployments.

Are these efforts intended to replace optical fiber in data centers?

Not necessarily. Optical solutions remain highly competitive for certain distances and topologies. The promise here is to provide an alternative for short, ultra-dense links where copper becomes problematic and optical might be “too costly” or complex, depending on the case.

When might we see these links in commercial AI racks?

Currently, what’s published ranges from prototypes, demonstrations, to industrialization plans. The maturity signal will be the integration with standard connectors and scaling pilots in actual data center environments.

Sources:

- IEEE Spectrum (RF Over Fiber: A New Era in Data Center Efficiency) (IEEE Spectrum)