The supply crisis in the memory market is no longer perceived as just another cyclical “bump,” but as a phase shift. As the artificial intelligence race absorbs manufacturing capacity, tension shifts from GPU architecture toward a more fundamental bottleneck: physics and the availability of memory. When products are scarce, the rules of commercial play also change.

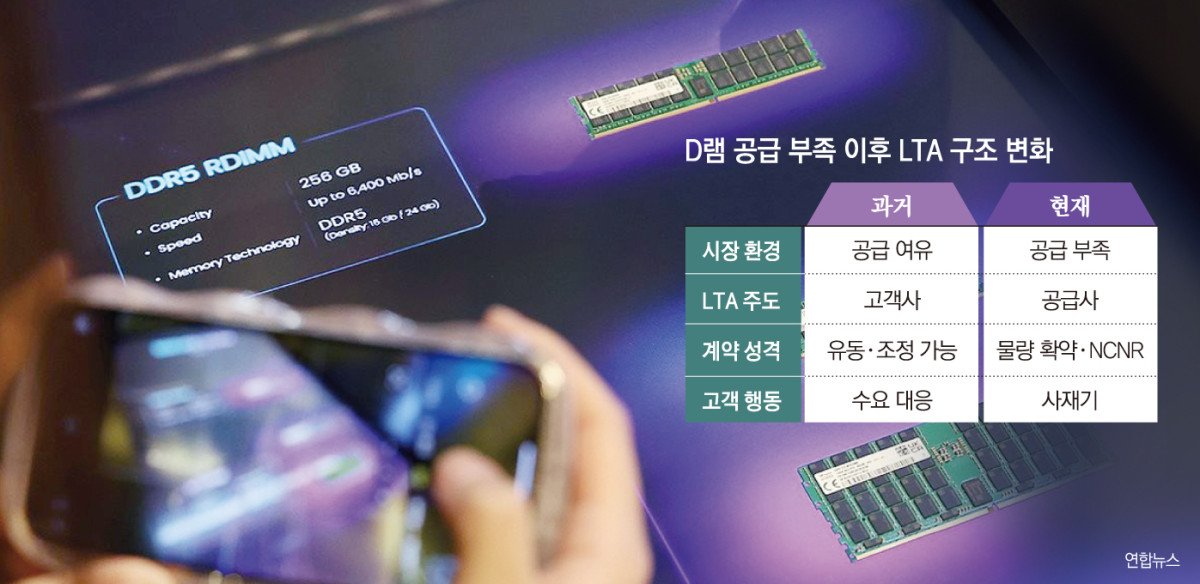

In this new scenario, long-term supply agreements (LTAs) are shortening, and negotiation dynamics are shifting from the buyer to the supplier. Where previously smartphone or PC manufacturers drove long-term contracts to secure volume and stability, now memory manufacturers themselves set the pace, with shorter contract periods—roughly 6 months to 1 year, according to industry sources—and structures that favor more frequent price reviews.

A market being “reordered” due to prolonged scarcity

The logic is simple: in a rising-price environment, suppliers gain margin if they can renegotiate earlier. Extended shortages encourage shorter contracts to reflect the new market prices with less friction. Simultaneously, manufacturer power is reinforced: those who control supply dictate the rhythm.

This pressure is fed by a structural phenomenon: capacity reallocation toward more profitable and strategic memories for AI, such as HBM. Tom’s Hardware, citing industry context, describes how factories shifting toward HBM for AI accelerators are leaving “commodity memory” (DDR and LPDDR) with fewer wafers available, just as demand remains strong in PCs, mobile devices, and servers.

From “flexible supply” to locked-in contracts

An increasingly common term in the sector is NCNR (non-cancellable, non-returnable). These are “non-cancelable and non-returnable” contracts, where the buyer commits to volume and terms with limited—or no—room for renegotiation. According to analysis cited by Samsung Securities in the provided text, this type of agreement is expanding from high-demand segments toward PCs, mobile, and high-volume DRAM, reducing the supply available in the spot market.

The direct consequences are twofold:

- Less liquidity in the spot market: if volume is “locked” in rigid contracts, there’s less free inventory for last-minute adjustments.

- More incentives to stockpile: those fearing delayed delivery tend to buy early, even when the final market conditions are not optimal.

Tom’s Hardware also describes a noteworthy symptom: the price inversion between DDR4 and DDR5 at certain times—an anomaly suggesting a shortage intentionally or opportunistically accelerated by supply decisions (reducing DDR4 production to free capacity for DDR5 and HBM).

Prices soaring “vertically” and extended timelines

The increase isn’t happening smoothly. In an example cited by Tom’s Hardware, the cost of a 16 Gb DDR5 chip rose from $6.84 to $27.20 between September and December 2025, in a context where certain categories of DRAM and NAND saw monthly increases of 80% to 100%.

In the short term, industry voices express concern: even with budgets allocated, immediate availability for certain memory profiles may be limited. Medium-term normalization is projected for 2027–2028, when new production capacities come online, according to some forecasts.

Real impact: PCs, mobiles, servers… and the “data center effect”

This reconfiguration of LTAs is not an abstract procurement issue; it affects costs, timelines, and technical decisions.

- Infrastructure upgrades: shifting from DDR4 to DDR5 (or other platforms) is no longer just a performance upgrade—it can become a matter of availability and total cost of ownership.

- Cluster planning and virtualization: projects relying on high memory density—such as databases, dense virtualization, analytics, and inference—become more sensitive to delays and price fluctuations.

- “AI tax” effect: the demand for HBM driven by AI raises the cost of conventional memories, transferring some of the rising costs of accelerators to other market segments.

Reuters has also highlighted a macro perspective: industrial reallocation toward AI is straining supply chains and increasing market interest in memory sector investments, driven by the prospects of higher margins and bargaining power.

What this means for companies: shifting from “price-based” to “risk-based” purchasing

The changing balance compels many organizations to rethink their approach:

- Window-based purchasing: if LTAs shorten, timing becomes critical.

- Designs with alternatives: maintaining options (e.g., DDR5 vs. legacy platforms, different densities, alternative suppliers) helps reduce exposure.

- Strategic inventory: in some cases, inventory stops being just a “cost,” becoming a “risk buffer” against allocations and delays.

The conclusion is clear: persistent scarcity leads to stricter contracts, shorter durations, and shifting power dynamics. This affects not only procurement spreadsheets but also architecture, schedules, and operational competitiveness.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an NCNR contract in semiconductors and why is it expanding?

An NCNR (“non-cancelable, non-returnable”) contract requires volume and conditions to be fixed, limiting buyer flexibility. In scarcity scenarios, it favors the supplier by stabilizing demand and reducing renegotiations.

Why can DDR4 prices increase even compared to DDR5?

When major manufacturers cut DDR4 production to reallocate capacity toward DDR5 and especially HBM, DDR4 supply diminishes. If existing DDR4 demand persists, prices can rise due to constrained supply.

How will this dynamic affect AI projects and data centers in 2026?

AI drives HBM demand and shifts manufacturing capacity, potentially reducing availability and increasing prices for commodity memories as well, impacting deployment timelines and costs.

What signals indicate that negotiation power is shifting toward manufacturers?

Shorter contracts, more volume commitment clauses, less price negotiation flexibility, and a trend toward rigid formats like NCNR are typical signs of a market where supply dominates.

via: Etoday