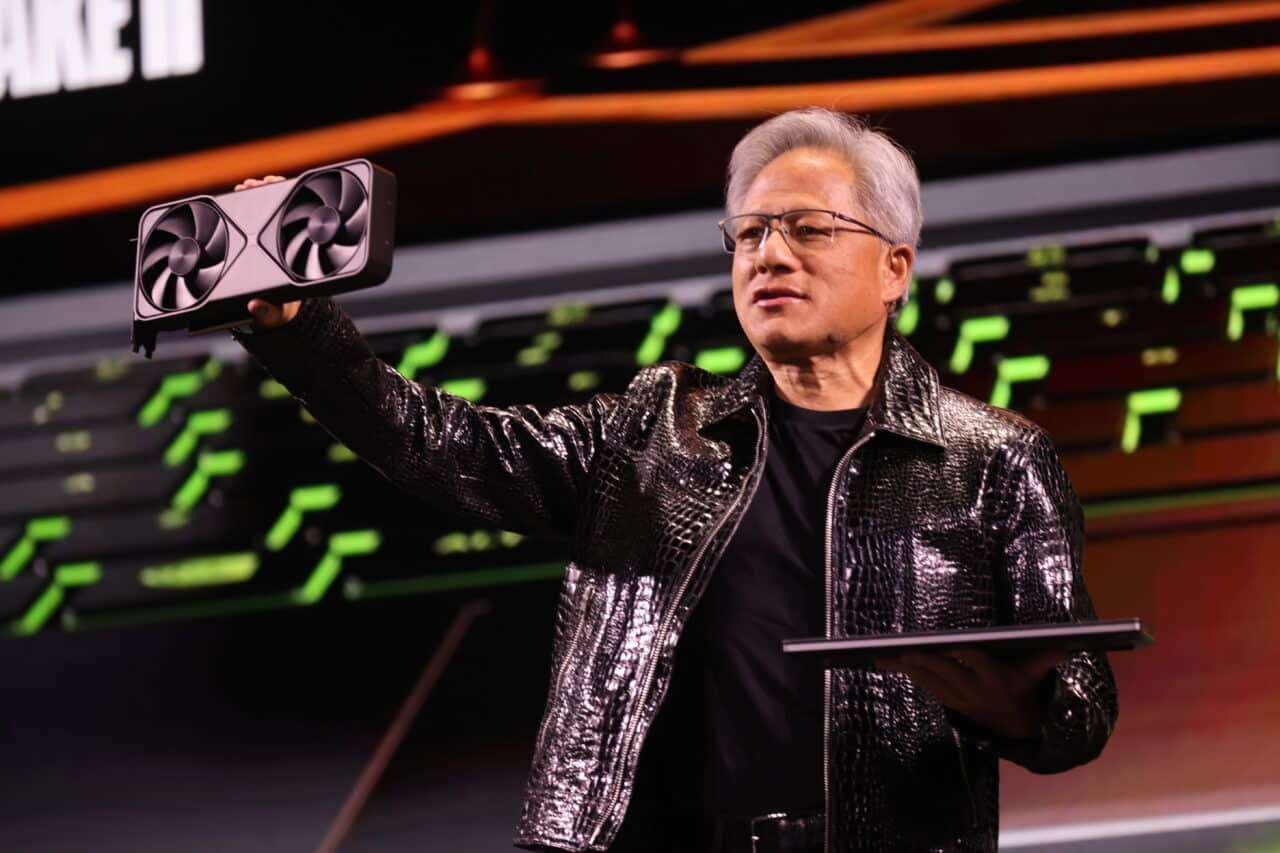

How close are China and the United States today in semiconductors? This question has been at the heart of tech geopolitics for years. NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang offered a striking and provocative answer: “China is just a few nanoseconds behind”. This statement, circulated by Chinese media, comes with an industrial policy message: Washington should allow U.S. tech companies to compete in the Chinese market to “increase its influence” and accelerate the global dissemination of its technology.

The executive, whose company has become a pillar of the current AI boom, describes China’s chip industry as “vibrant, entrepreneurial, and highly technological”, with abundant talent and fierce internal competition. His argument is that cutting off access to this market reduces opportunities for U.S. firms and does not prevent China from developing its own capabilities. Hence his direct call: “We have to compete.”

The “nanoseconds” metaphor — a unit from electronics and telecommunications — functions as a rhetorical hook to express proximity rather than a literal technical measure. But the underlying message is clear: Huang suggests that the gap has narrowed and that inertia points to a more self-sufficient China in semiconductor design and manufacturing.

What exactly did NVIDIA’s CEO say?

- On technological distance: “China is just a few nanoseconds behind the U.S.”

- On strategy: The U.S. should allow its tech sector to compete in China to “maximize economic success” and geopolitical influence through technology dissemination.

- On the Chinese environment: “Abundant talent and intense competition make the country highly potential for R&D and chip manufacturing.”

- On foreign investment: Huang trusts that China will keep its doors open to investments and competition from outside firms, which, in his view, benefits both China and global players.

The thesis sums up as follows: Competing in China not only strengthens the position of American companies but also increases the presence and soft power of the U.S. in strategic sectors. Restricting activity — the implicit message — does not halt third countries’ technological progress but limits Washington’s influence capacity.

Why does this statement matter (beyond the eye-catching headline)?

Huang’s intervention touches multiple nerves:

- The AI race

The current race for artificial intelligence relies heavily on high-performance chips, HBM memory, interconnects, and software. NVIDIA dominates AI acceleration, and its views on competition and markets influence suppliers, clients, and regulators. - The supply geopolitics

Semiconductor supply chains are global and fragile: design, EDA, IP, wafers, lithography equipment, advanced packaging, and training software. Any additional barriers alter costs, timelines, and risks, raising concerns among automakers, consumer electronics, telecoms, and hyperscalers. - The export control debate

U.S. restrictions in recent years have aimed to limit access to cutting-edge technology. Huang’s message suggests that, even with limits, the distance isn’t insurmountable, and that collaboration/competition might be more effective in maintaining U.S. influence than isolation. - The mirror effect

Industry leaders’ comments serve as market barometers: major global clients don’t want uncertain supply or blockages in software and hardware, pushing instead towards standardization, volumes, and predictable costs.

What does “a few nanoseconds” mean in practice?

Taking the phrase literally, it’s not a technical indicator (the latency of a chip alone doesn’t encompass manufacturing nodes, wafer yields, cost per transistor, or software ecosystem). However, the core message can be understood as:

- China has narrowed the gap across several links: from SoC design and accelerators, to mature node manufacturing and packaging.

- The country is massively investing in training and manufacturing capacity, as well as promoting self-developed platforms (GPU/AI/EDA) in response to export restrictions.

- The gap persists in lithography equipment, materials, and critical IP, but the momentum is unmistakable.

Huang uses the language of time (nanoseconds) to emphasize that, in his view, the difference now isn’t measured in years but in details that can be closed through open competition.

Compete or restrict: the two paths the sector presents

- Compete: sell tailored products to regulations, invest in local ecosystems, deploy services and technology with governance. The potential rewards: influence, de facto standards, and volumes to lower costs.

- Restrict: prioritize national security and control of technology; the risk: accelerate substitution with domestic alternatives, fragment the market, and lose influence channels.

The NVIDIA CEO clearly positions himself in the first group: “We have to compete”.

What industry gains and risks with openness

Gains:

- Markets with huge demand and rapid adoption.

- Accelerated feedback to iterate hardware and software.

- Network effect: more customers and developers feed into the ecosystem (frameworks, libraries, tools).

Risks:

- Knowledge transfer to competitors.

- Dependence on sensitive supply chains.

- Conflicts with regulations that may limit products or services.

The balance always hinges on what is offered, how its use is controlled, and with what safeguards for compliance.

Talent and internal competition: the two Chinese “levers” Huang cites

The executive highlights two key factors unique to China:

- Talent: the country graduates thousands of engineers every year and attracts professionals trained abroad.

- Internal competition: the pressure among domestic companies accelerates R&D and commercialization cycles.

Together, these levers facilitate turning prototypes into products and advancing technologies rapidly. For anyone competing, this presents an additional challenge: not only is leadership necessary, but speed must match an extraordinarily dynamic market.

How the landscape might evolve

- Dual paths: coexistence of global products with adapted versions tailored to regulatory frameworks.

- Focus on software: even when hardware limits exist, software layers (compilers, libraries, runtimes) impact performance and usability.

- Parallel ecosystems: incentives to develop full domestic stacks (chips, tools, frameworks) with partial interoperability.

- Memory and packaging battles: competition for HBM and advanced packaging (CoWoS, SoIC, etc.) will be critical for next-generation AI performance.

- Increased investment in talent: both in China and the U.S., training and access to experts will determine pace of progress.

Interpreting NVIDIA’s statement as a user or industry player

- It’s not a medical report: the metaphor of “nanoseconds” doesn’t replace technical reports or production data.

- It’s a thermometer: a central market player suggests that advantage is narrowing and that competition in AI will mainly be won on margins: overall costs, software ecosystem, access to markets, and talent.

- Implication: those planning infrastructure or products should consider openness scenarios with China, as well as scenarios of separation, with alternative providers and portable architectures.

A message to two audiences

Huang speaks to Washington, asking for room to compete in China, and speaks to Beijing, recognizing potential and openness to investment, with the expectation of healthy competition that benefits both sides. In between are clients — from hyperscalers to startups — who need predictable supply, mature software, and manageable costs.

The CEO presents an uncomfortable truth to advocates of total decoupling: Closing doors does not stop engineering effort or entrepreneurial initiative on the other side; it may reduce the ability to influence standards and markets.

Conclusion: competition as industrial policy

The statement that China is “a few nanoseconds” from the U.S. should not be read as a technical judgment but as a call for open competition. Ultimately, it’s about a stance: influence is built through competition, not self-suspension from the world’s largest markets.

It remains to be seen whether the message resonates in policy circles. But in industry — where every manufacturing node, software interface, and month of advantage count — effective competition continues to be the variable that, again and again, closes the gaps faster than any slogan.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Jensen Huang say China has already surpassed the U.S. in chips?

No. Reports indicate he used a metaphor — saying China is “a few nanoseconds behind” the U.S., emphasizing the reduction of the gap, not asserting technical superiority.

What concrete proposal does NVIDIA’s CEO make?

He suggests that the U.S. should allow its tech companies to compete in China to expand influence and disseminate technology, instead of just limiting access.

Why mention “talent” and “internal competition” in China?

Because these are key levers explaining the rapid progress in Chinese R&D and manufacturing: many engineers and a market that pushes companies to iterate quickly.

What are the implications for companies and users?

The landscape is dynamic: global products and customized versions can coexist; software and the ecosystem will weigh as heavily as silicon; and planning should be resilient (alternative suppliers, portability) amidst regulatory changes.

via: MyDrivers