Intel has spent years trying to shift the industry perception from solely a CPU manufacturer to a serious player in foundry services. Suddenly, a series of leaks and analyst notes have pushed Intel Foundry back into the spotlight: not as an immediate substitute for TSMC, but as a selective partner for specific projects involving Apple, NVIDIA, AMD, Google, and Broadcom.

The nuance is important. This isn’t about a massive “changing of sides,” nor will the industry abandon TSMC tomorrow. What’s emerging is a more surgical approach to the supply chain, where Intel competes on two fronts that today are as significant as lithography nodes: capacity in the U.S. and advanced packaging (the “how chips are assembled”) for high-margin, strategically important products.

What the leaks suggest: clients, nodes, and a common thread

The scenario painted by these shared reports online is that of Intel as a provider for data center workloads, AI accelerators, and ASICs (custom chips), where capacity availability and packaging determine deployment speed.

- Apple appears linked to projects that, in the initial phase, would fit better on the back-end (packaging and assembly) and internal/infrastructure chips, rather than volume migration of their flagship consumer SoCs. The industrial logic is clear: diversify risk and gain leverage without suddenly breaking away from TSMC’s dominance.

- NVIDIA and AMD are seen as candidates to utilize Intel 14A for server SKUs in the second half of the decade. The conservative view: Intel as a secondary supplier for specific components, alleviating bottlenecks and reinforcing domestic production in a context where geopolitics is now part of product design considerations.

- Google is considered the most technical case (and thus more credible in terms of motivation): a specific TPU is mentioned, associated with a variant of EMIB (Intel’s interconnect technology for bonding chips/chiplets with high density). In other words: Google isn’t “buying a node,” but rather acquiring an integration method to scale their own accelerator.

- Broadcom fits the typical pattern for their network ASICs and silicon: long lifecycle, reliability demands, high margins, and supply chain sensitivity. In these cases, packaging and capacity matter as much (or more) than chasing the most advanced node.

Why packaging might be more decisive than the node

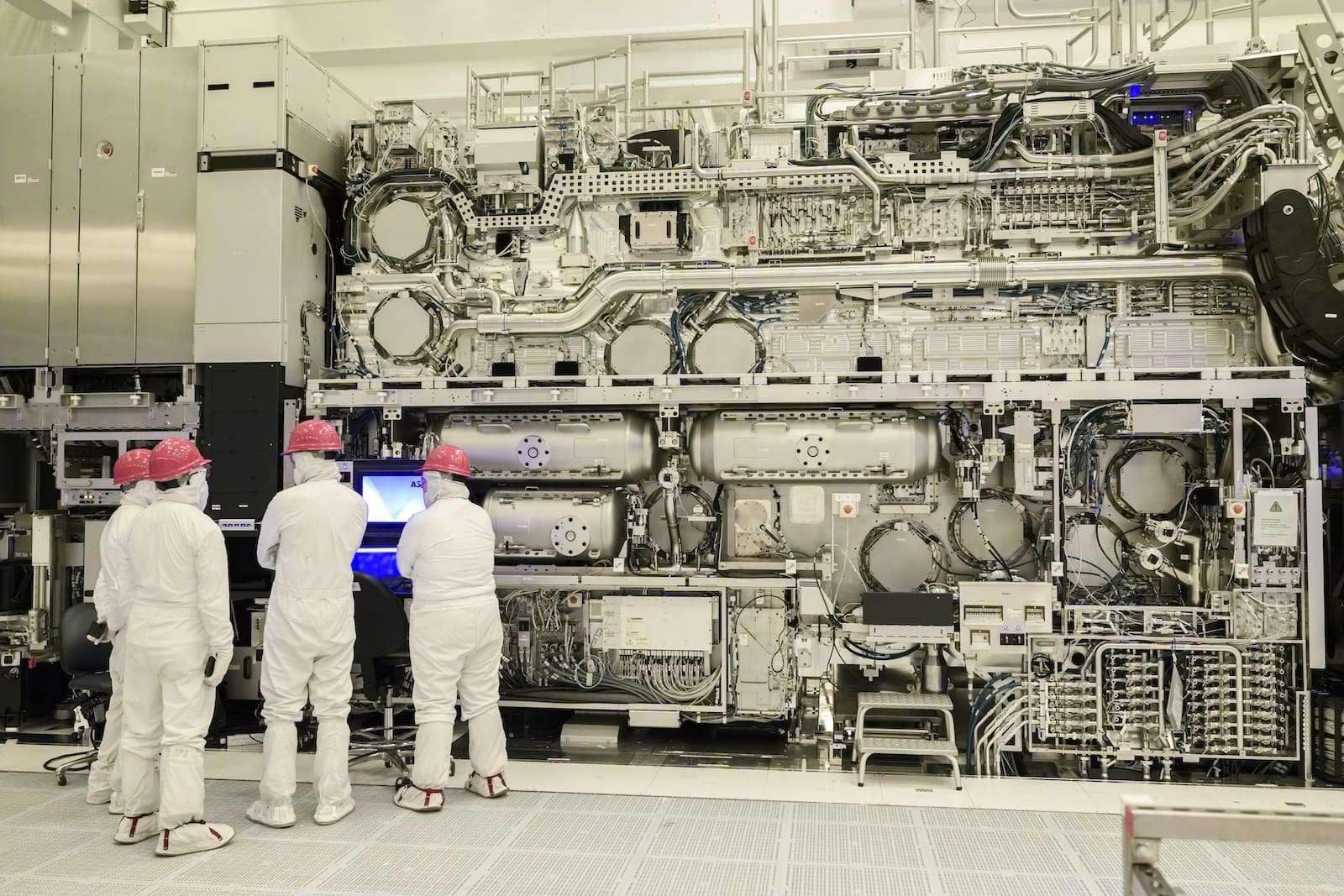

The public conversation about semiconductors usually revolves around “2 nm vs 3 nm,” but the reality of AI has shifted the focus: advanced packaging and heterogeneous integration are the performance multipliers for modern GPUs, TPUs, and ASICs.

In practice, many leading AI chips are not a single “monolith,” but sets of chiplets connected via high-speed interconnections and close memory (HBM). If this assembly becomes a bottleneck—due to capacity, manufacturing performance, or technology availability—the industry stalls even if the node itself is excellent.

That’s where Intel has an opportunity: it doesn’t need to “beat” TSMC across everything; it just needs to be indispensable in specific layers (packaging, assembly, integration, localized production) to capture strategic projects.

The weak point: execution, yields, and realistic timelines

The same notes fueling optimism often include the most critical caveat for investors: execution. These leaks talk about yields and milestones for high-volume manufacturing (HVM) for specific product families and highlight Panther Lake as a key indicator of process maturity.

In other words, Intel may have a compelling narrative, potential clients, and an attractive portfolio… but the ongoing question remains: Can it deliver reliably, at scale, and at competitive costs?

Implications for the market: less faith, more strategy

If this pattern holds, the most significant shift won’t be “Intel takes the throne from TSMC,” but something more subtle:

- Real diversification: big tech companies want credible contingency plans.

- Layered supply chain: one provider for leading-edge nodes, another for assembly, yet another for local capacity.

- Sovereignty and supply security: “Made in USA” (or “Made in EU”) moves from marketing to an integral part of product roadmaps.

- Packaging as a key player: the AI race is decided as much by “how you manufacture” as by “how you assemble.”

Comparison table: manufacturing and integration options used by big tech

| Approach / Provider | Typical Strengths | Typical Limitations | Best Fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSMC (foundry + advanced packaging) | Leadership in high-volume production and mature ecosystem | Geographic dependence and capacity pressure for AI projects | High volume, cutting-edge nodes, roadmap continuity |

| Intel Foundry (node + EMIB/Foveros/packaging) | Vertical integration, focus on capacity in the U.S., proprietary packaging portfolio | Perceived risks in execution and ramp-up | ASICs/server/AI where packaging and localization matter |

| Samsung Foundry | Industrial capacity, options in advanced nodes, proprietary packaging | Variable competitiveness depending on generation and client type | Sourcing diversification, specific SoCs, and projects |

| Multi-sourcing strategy (mix of providers) | Resilience and negotiation leverage, dependency reduction | Operational complexity, validation, and compatibility issues | Hyperscalers and strategic chips with high margins |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Intel 14A and why is it interesting to NVIDIA or AMD?

It’s a future Intel node within its roadmap of advanced processes. If it proves competitive, it can be used to manufacture specific chips (especially servers) and, importantly, diversify capacity and production locations.

Why would Apple want Intel if it already works with TSMC?

Because the risk isn’t just technical – it also involves capacity, geopolitics, and dependence. For certain internal chips (infrastructure, ASICs, data center components), having an industrial alternative can be strategic even if TSMC remains the main supplier.

Which weighs more today in AI: the lithography node or advanced packaging?

In many modern AI systems, advanced packaging (how chiplets and HBM memory are connected) is just as critical as the node itself. It can limit performance, power consumption, cost… and, most importantly, the availability of the final product.

Does this mean Intel has already “won” over TSMC?

Not exactly. It means Intel might be regaining relevance as a partner in specific projects. The market isn’t won by headlines, but by execution: yields, timelines, costs, and delivery capacity.