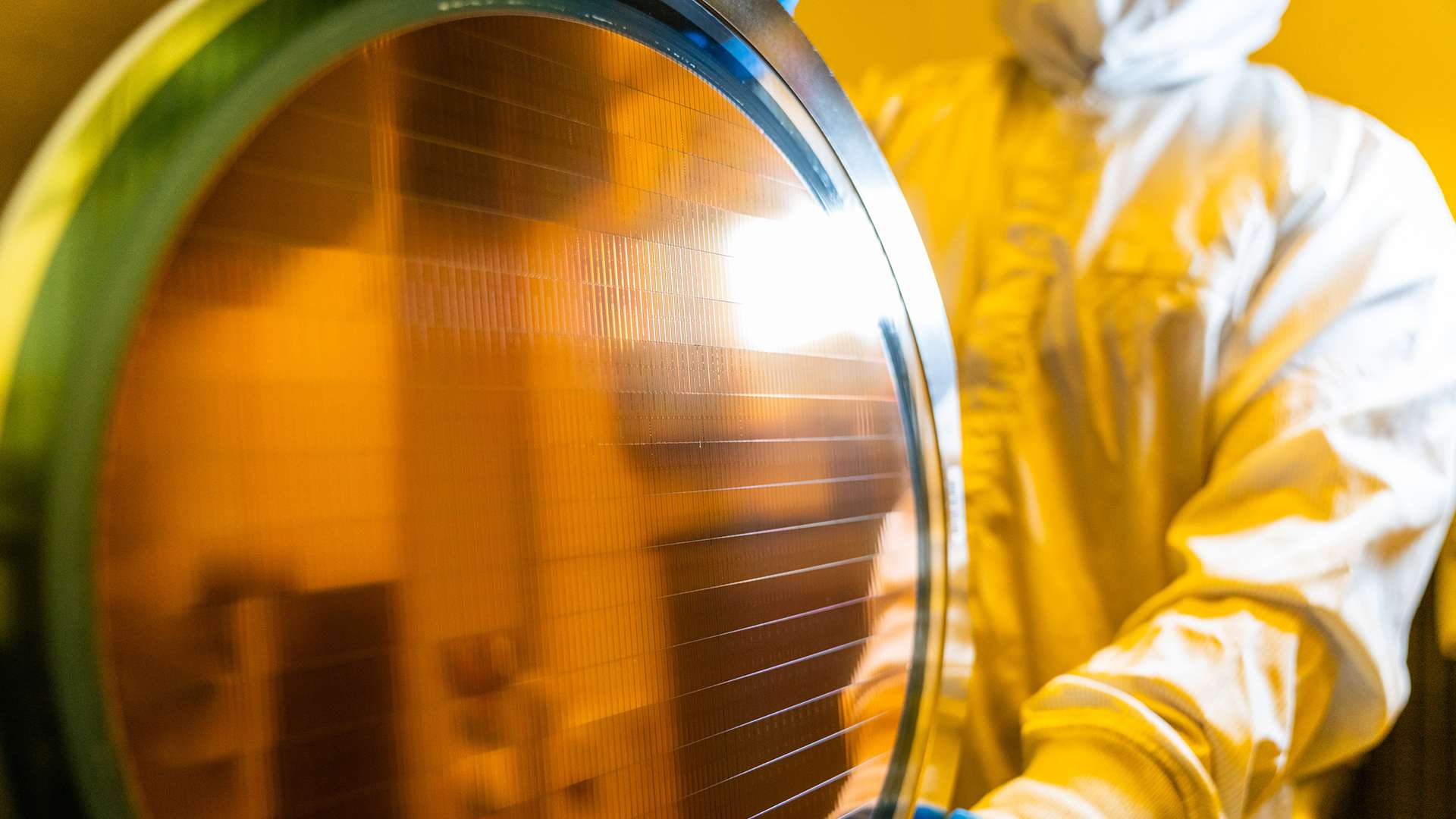

Intel is once again at the center of the board. The company is exploring ways to breathe new life into Intel Foundry Services (IFS), its wafer manufacturing business, and one of the most talked-about options involves selling up to 49% of the subsidiary to external investors. On the table, there is no immediate IPO or full spin-off, and the reasons are not solely financial: Washington insists that Intel maintains at least 51% control within five years or face penalty clauses. Amid capital needs, government oversight, and a much more cautious investor appetite than Santa Clara expected, IFS is moving forward on a tightrope.

What Intel has said and why it matters

At the Global TMT Conference 2025, CFO David Zinsner made it clear: “Intel must control at least 51% of its wafer manufacturing business within five years; otherwise, penalty clauses will be enforced.” This isn’t an idle statement. It serves as a reminder that the agreement with the U.S. government — which invested $8.9 billion in exchange for a 10% stake — includes safeguards to prevent a strategic asset from falling outside U.S. control.

Furthermore, this framework stipulates an additional 5% increase in public investment if Intel’s stake in its factories drops below 51%. In other words: The White House has a “trump card” to uphold industrial sovereignty over silicon. In this environment, any sale operation has a ceiling, and any potential buyer knows that the controlling partner is not negotiable.

Market reality: who would buy 49%… but not control?

Legally, proposing to sell up to 49% may satisfy regulatory requirements on paper, but it raises other practical questions. Who wants to invest billions in a business where they won’t have strategic control, won’t appoint management, and yet will share operational and reputational risk? There aren’t many candidates.

Zinsner hinted that, although a partial sale is theoretically feasible, the dilution risk for shareholders and the complex warrants structure linked to public funding make it unlikely that the extreme scenario (selling 49% in one go) will happen soon. Investor reception so far remains tepid: buying without governance doesn’t appeal to funds and complicates any future IPO by reducing the cash flow percentage attributable to the parent.

A decade of ambition… constrained by the calendar

IFS was created to compete head-to-head with leading foundries. Intel’s leadership has reiterated the need for capital-intensive investments, anchor clients, and time to demonstrate consistent manufacturing yields. Market pressure — and now also political timing — accelerates decision-making.

In 2022, the company launched SCIP (Semiconductor Co-Investment Program) with a clear goal: raise $26 billion under the CHIPS Act framework, attracting private capital without losing control. The strategy was only partly successful. Intel secured co-financing for certain assets, but the core approach remained unchanged: it will continue sharing ownership of some factories even while maintaining management control and technological direction.

The government’s direct involvement as a stakeholder bolsters this architecture: public money in exchange for control conditions. Investors interpret this pragmatically: participation is possible, but imposing changes isn’t straightforward.

The political equation: White House steering the wheel

There’s also a political factor influencing these moves. Market analysis suggests that The White House intervened to prevent IFS from being completely spun off or sold. In the midst of a geopolitical reconfiguration, Washington views IFS as a sovereignty asset. And the current administration — with Donald Trump setting the tone — closely monitors that the project doesn’t change hands or cede maneuvering room to foreign partners.

This oversight explains why an independent IPO or a full spin-off followed by a sale are unlikely scenarios. Such options could clash with control clauses and trigger a regulatory Pandora’s box. For now, financial engineering remains within the 49% boundary.

What if Intel manages to sell that 49%? Pros and cons

Potential advantages:

- Capital infusion without losing majority control: funding capex for new fabs and nodes, reducing debt, or accelerating the roadmap.

- Market signal: a flagship investor can serve as a “trust seal” for IFS’s viability.

- Strategic flexibility: financial partners can open doors to commercial alliances.

Obvious risks:

- Reduced cash flow share from IFS, which pressures Intel’s future valuation during additional partial sales or IPOs.

- Governance complexity: with the state as a “referee”, private investors will have limited leverage to demand change, discouraging activist stakeholders.

- Execution risks: if technological or cost milestones are delayed, the new partner may demand protective clauses that increase capital costs.

Who might be interested?

The question hangs in the air: TSMC, Samsung, China? Given the high political stakes, it seems unlikely that sensitive foreign actors — especially Chinese — could approach a stake that, by volume, would almost occupy negative control. A more realistic scenario involves aligned sovereign funds, major U.S. asset managers, or industrial consortia with exposure to defense and critical infrastructure. All of them will, of course, seek discounts or preferential terms to safeguard their investment.

What the market seeks: margin visibility and anchor clients

Investors aren’t just after structure; they want traction. The missing piece in this puzzle isn’t legal but operational: firm orders and margins. For a 49% stake to be investment-worthy, Intel needs to demonstrate:

- Material and diversified third-party client portfolio, beyond internal demand.

- Clear process milestones (performance, wafer costs) relative to public targets.

- Discipline with capex and a credible schedule aligned with public support thresholds.

If these elements align, the conversation shifts: the 49% stake ceases to be a costly rescue and becomes leverage to accelerate the industrial plan.

What this debate reveals about the future of silicon in the U.S.

Beyond Intel, this episode illustrates the new model with which the U.S. aims to rebuild its advanced manufacturing capacity: public-private co-investment with public control over critical sectors. It’s guided capitalism: markets fund, the government governs.

For Intel, the message is twofold. Support exists — proven by the $8.9 billion check — but so do conditions: majority control, penalty clauses, and a political scenario where total sale isn’t an option. The company must navigate this tension while convincing investors that IFS can be profitable in the world’s most demanding league.

And now what?

In the short term, expect selective operations: co-investment vehicles for assets per plant or node, minority stakes with preferential terms, and commercial agreements that secure volumes. A 49% “in one block” isn’t out of the question, but it’s not the favored option for either markets or regulators.

Meanwhile, IFS will continue searching for clients, securing financing under SCIP, and meeting milestones to keep the public faucet open. Selling a significant part of the business without losing control could be a tool. Not the only one, and certainly not the simplest.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) — focusing on long-tail searches

What does it mean that Intel could sell up to 49% of IFS and still control the foundry?

This means Intel could sell stakes in its manufacturing business without losing a majority. The U.S. deal requires that 51% be maintained within five years, or face penalties. For investors, buying 49% entails financial exposure with limited decision-making power.

Why is a full IPO or a complete spin-off of Intel Foundry Services unlikely now?

Because the public aid framework — $8.9 billion for 10% — includes control clauses and options for additional investment if the 51% stake is endangered. A full divestiture or an independent IPO could clash with these conditions and Washington’s strategic priorities.

What impact would selling 49% of IFS have on Intel shareholders?

It would bring capital inflow to fund capex, but also reduce cash flow share from the foundry business. This could pressure future valuation in an IPO or additional sales, complicating governance with more stakeholders.

Useful long-tail SEO keywords

- Is investing in the 49% of Intel Foundry Services under the CHIPS Act a good idea?

- US government conditions to maintain 51% stake in Intel IFS

- Risks for investors in partial sale of semiconductor foundries

- Differences between Intel’s SCIP co-investment and selling 49% of IFS

In summary, Intel is considering selling up to 49% of its foundry, without relinquishing control, as mandated by public money regulations. It’s a feasible, complex, and politically sensitive operation. As with most things in silicon, its success will depend not only on finances but also on something more pragmatic and decisive: timely manufacturing, cost control, and willing clients.

via: tomshardware