The race for Artificial Intelligence is not being decided solely by GPUs. The new silent, expensive, and increasingly critical bottleneck is memory: how much can move per second, how close it can be to the processor, and how much energy is consumed to keep that steady data flow. In 2026, with data centers expanding at a pace that tests the electrical grid and supply chains, the focus shifts toward a component that for years seemed “commoditized”: DRAM.

The signs are clear. Companies like TrendForce have significantly raised their price hike forecasts for conventional memory, in a market strained by AI infrastructure demand and large manufacturers’ preference for more profitable products like HBM (High Bandwidth Memory). Simultaneously, this impact is beginning to infiltrate consumer electronics: several PC manufacturers have started evaluating alternative supply sources in China amid global shortages, according to recent reports.

Amid this context, a notable development has emerged: SoftBank, through its subsidiary SAIMEMORY, and Intel have signed a collaboration agreement to advance the commercialization of a technology called Z-Angle Memory (ZAM). This next-generation memory aims to combine high capacity, high bandwidth, and low power consumption, targeted at training and inference workloads for large-scale models.

A timeline agreement: prototypes in fiscal year 2027 and commercialization in 2029

The partnership was finalized on February 2, 2026, with official milestones charted: prototypes during the fiscal year ending March 31, 2028 (FY2027) and market launch goal in FY2029. SAIMEMORY, founded in December 2024, will lead development and market entry, while Intel will provide technological foundations and innovation support.

SoftBank frames this initiative as part of its strategy to strengthen infrastructure related to data centers and AI, emphasizing a shift from massive training to operational inference, where moving large volumes of data to accelerators becomes critical.

What is ZAM and why is the “Z axis” important?

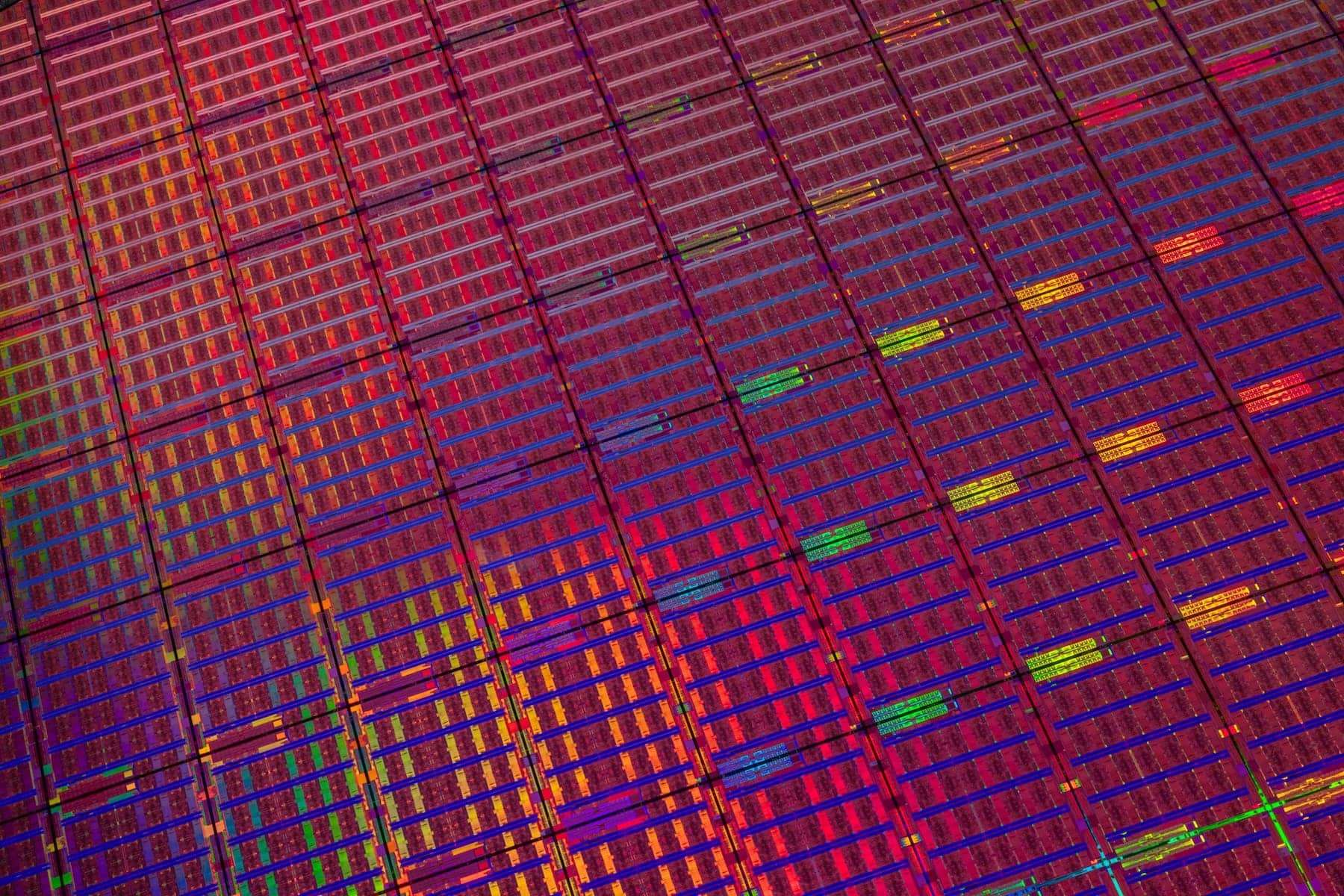

ZAM introduces a memory architecture that looks upward: the name references the Z axis, meaning vertical stacking of structures to increase capacity and performance without increasing physical size. The goal, in simple terms, is to bring more “fast” memory closer to the compute chips, reducing typical frictions—latency, power consumption, and packaging limitations.

Although still in early stages, sector analyses view this as an attempt to overcome the current limitations of HBM, which has been key to AI due to its enormous bandwidth but also imposes compromises on capacity and costs. Essentially, the industry needs memories that don’t force a choice between “more bandwidth” or “more capacity.”

The technical component Intel brings: Next Generation DRAM Bonding (NGDB)

The core technological work behind the agreement lies in Intel’s ongoing project Next Generation DRAM Bonding (NGDB), developed within the Advanced Memory Technology (AMT) program managed by the US Department of Energy and the National Nuclear Security Administration, with support from national labs such as Sandia.

Sandia has publicly shared significant advancements: its description indicates that, in high-bandwidth memory, bandwidth is often improved at the expense of other factors like capacity. NGDB aims to reduce that trade-off, “bringing” performance closer between HBM and conventional DRAM through energy efficiency enhancements. In one update, the lab showcased test assemblies with a base layer and eight vertically stacked DRAM layers, emphasizing that recent prototypes already demonstrated functional DRAM via this stacking approach.

Sandia summarizes its ambition with a concise statement that underscores why this matters: creating high-performance memory suitable for mass production.

Money, industry, and the battle for supply

While the official announcement focuses on the roadmap, specialized media indicate that SoftBank plans to invest around 3 billion yen to reach the FY2027 prototype milestone, according to industry sources cited in coverage.

This move is also viewed as a strategic gamble: Japan played a significant role in memory development in previous decades and now seeks positions in critical areas of the AI supply chain. If successful, ZAM would not only be a component but a lever to reduce technological dependency in a market where demand has become political, industrial, and geopolitical simultaneously.

The global landscape remains tense: shortages of memory and reallocations toward AI products are disrupting prices, launch schedules, and sourcing decisions—from data centers to consumer laptops.

What remains to be proven

Currently, ZAM is a promise with a timeline, not a product on the shelves. Between the announcement and large-scale manufacturing lie well-known semiconductor challenges: yield performance, thermal dissipation in dense stacking, packaging complexity, standardization for server platforms, and, most importantly, real costs compared to established alternatives.

However, the market message is clear: if AI is a race for infrastructure, memory is becoming the segment where missteps are easiest. When the industry stumbles, opportunities for new architectures, unlikely alliances, and historic reentries are born.

Frequently Asked Questions

What differentiates HBM memory from “standard” DRAM (DDR4/DDR5) in AI servers?

HBM prioritizes extremely high bandwidth thanks to advanced packaging and proximity to computing chips, which is crucial for powering GPUs/accelerators; DDR is used as general main memory, typically offering more flexibility and lower cost per capacity but with less bandwidth per package.

When might the first commercial systems with Z-Angle Memory (ZAM) appear?

The announced plan targets prototypes in FY2027 and commercialization in FY2029, so their arrival in final products depends on industrial development and manufacturer agreements.

Why has memory become a bottleneck for Artificial Intelligence?

Large models and scaled inference require continuous data movement to accelerators. If bandwidth or nearby capacity is lacking, GPUs may idle, increasing training and service costs.

How does DRAM and NAND scarcity affect PC users and businesses?

When prices rise or supply is restricted, manufacturers adjust configurations, delay launches, or seek alternative suppliers; for companies, this can translate into higher server and upgrade costs.

via: trendforce