The race for Artificial Intelligence is no longer limited to chatbots or language models. The next battlefield is taking shape in the physical world: humanoid robots capable of learning, moving, and working in real environments. According to industry analysts, China is expected to concentrate the vast majority of global humanoid robot installations by 2025, positioning itself advantageously just as the industry begins to set norms, platforms, and de facto standards.

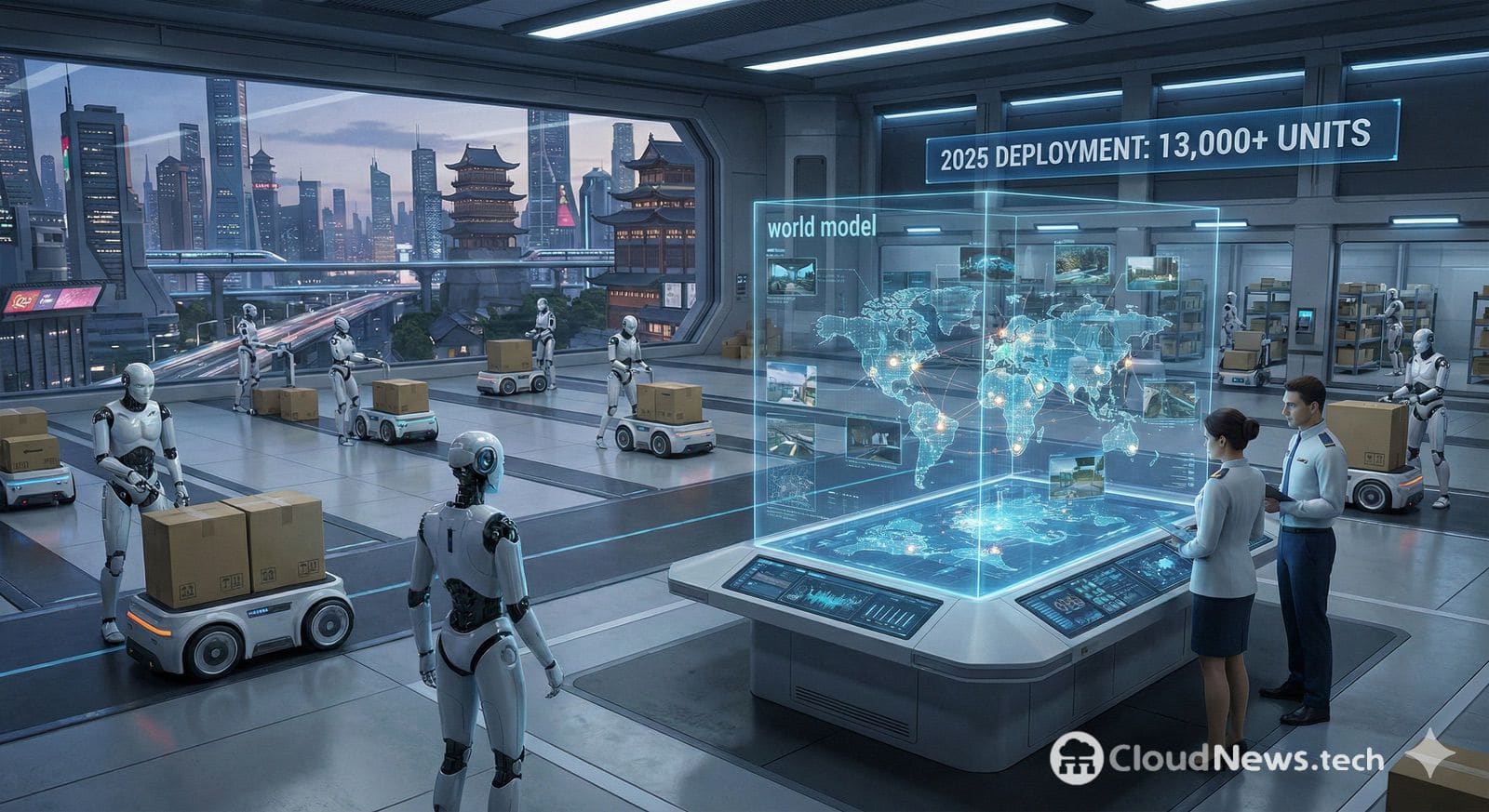

The most striking figure is the deployment distribution: around 16,000 humanoid robots installed worldwide in 2025, of which nearly 13,000 would be in China. In other words: the country is not only researching or prototyping but placing hardware into the field—in factories, laboratories, educational centers, and, at an early stage, commercial applications—in a phase where “the first to deploy” can influence the ecosystem for years.

From LLMs to “world models”: AI that understands physics

For robotics, language models (LLMs) are useful but insufficient. The major leap is associated with so-called “world models”: neural networks trained with video and images to simulate physical dynamics, object interaction, spatial continuity, and causality. In other words: systems that learn how “the world works,” not just how to describe it in text.

This approach is especially relevant because, in robotics, the bottleneck is not only abstract “intelligence,” but also the ability to perceive, plan, and execute under variable conditions: different lighting, surfaces, obstacles, tools, and surrounding people. Training for this is costly and complex: it requires data, simulation, annotation, validation, and tight integration with sensors and actuators.

Within this context, the moves by companies like NVIDIA make sense, as they push a comprehensive “platform approach” for robotics and physical AI, leveraging tools and models to accelerate training and simulation. The clear thesis: whoever controls the stack (foundation models + data + simulation + hardware) can become the reference provider.

China: manufacturing advantage, iteration speed, and “good” standards through adoption

The Chinese advantage is not necessarily “having the best robot in the world” today, but deploying many sufficiently good robots at scale. The logic resembles other tech wars: standards often emerge through mass adoption, compatibility, and integration costs, not only technical brilliance.

Contributing to this momentum is the industrial backbone: if China can leverage its manufacturing base to produce, iterate, and reduce costs, it can create a virtuous cycle: more robots deployed → more real-world data → better models → improved robots → further deployment.

Some estimates attribute a substantial share of shipments to specific Chinese companies (a distribution that leaves Western players far behind for now). And while Western projects feature impressive demos and corporate backing, the uncomfortable question is becoming louder: are spectacular prototypes enough if most hardware is installed elsewhere?

Open source, datasets, and the quiet battle over the “language” of robots

Another strategic lever is openness. In software, standards tend to consolidate when thousands of developers build on a common foundation. In robotics, this could mean datasets, models, and tools that make it easier for universities, startups, and integrators to adopt specific training and deployment methods.

In this vein, the debate over “who opens what” is not ideological: it’s economic and geopolitical. An accessible model or dataset can become a starting point for an entire community, which eventually establishes conventions: formats, APIs, training pipelines, benchmarks, and safety practices.

Meanwhile, companies like NVIDIA promote foundational models for robotics, though often under licenses that don’t fully align with strict open-source definitions. The result is a market with tensions: on one side, the power of an industrial stack; on the other, the “stickiness” of open principles to foster a lasting ecosystem.

Consolidation risk: too many players but a common goal

Ironically, China’s own dynamism poses a risk: excessive competition among many companies, duplicating efforts and stressing profitability. Authorities involved in the country’s economic planning have publicly warned against bubbles and unnecessary repetition, suggesting a plausible path toward sector consolidation: concentrating capital, talent, and product lines.

However, even in a scenario of consolidation, one factor may remain: the infrastructure, deployed robots, and emerging standards. This is precisely what concerns Western analysts: even if some companies disappear, the technological “ground” would persist.

The West: alliances, advanced engineering… and the execution challenge

The Western side is not starting from zero. Japan has decades of industrial experience in robotics. Europe maintains critical advantages in machinery and advanced value chains. The US remains a leader in software, high-performance semiconductors, and platforms. Many analysts emphasize the question: can the Western bloc turn these capabilities into rapid, scalable deployment?

Because in humanoid robotics, more than in other fields, “time-to-deploy” is crucial: when technology becomes tangible, the market learns from implementation, not just demos. And in this respect, China is trying to set the rhythm.

Comparison table: why deployment could determine the standard

| Aspect of Competition | China (2025 Trend) | West (2025 Trend) | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deployment of humanoid robots | Very high (majority of estimated global total) | Lower in comparison | The standard tends to emerge where more hardware is operational |

| Industrial advantage | Mass manufacturing and rapid iteration | Advanced but more fragmented supply chain | Cost/volume advantages favor faster adoption and improvement cycles |

| Data/models ecosystem | Promotion of datasets and models for adoption | Strength in models and platforms, various licenses | Open approaches can accelerate community; proprietary ones may boost performance |

| Market risk | Too many players → potential consolidation | Fewer players but slower investment and execution | China may streamline the market without losing deployed ground |

| Strategic objective | Lead in hardware + standards | Lead in software + platforms + alliances | Who connects software and real robots at scale will win |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a “world model” in robotics, and why is it important?

It is a type of AI model trained with visual data (videos and images) to represent physical dynamics and spatial relationships. It is crucial for enabling robots to act effectively in real environments, beyond just “talking” or classifying text.

Why does the number of deployed robots matter more than just demo quality?

Because deployment generates real-world data, integrates with industrial processes, and establishes technical conventions. Often, standards arise through adoption and compatibility rather than only through excellent laboratory demos.

What role do platforms like NVIDIA’s Isaac or foundational robotic models play?

They aim to accelerate training, simulation, and development of physical capabilities (vision, planning, control). Their goal is to become the “stack” basis on which third parties build robots and applications.

Can the West regain ground in humanoid robots?

Yes, but it requires execution: sustained investment, industrialization, alliances, and rapid deployment. The Western advantage often lies in advanced engineering and a global ecosystem; the challenge is translating that into volume and real-world adoption.

Sources:

- Tom’s Hardware, “Robotics and world models are AI’s next frontier, and China is already ahead of the West…”

- Tech in Asia (via Counterpoint/SCMP), data on global installations and China’s market share in 2025

- NVIDIA Newsroom, announcement and context about Cosmos for robotic/physical AI