In the major international automotive halls, the script is changing. Where previously the spotlight was on supercars, futuristic prototypes, or record-autonomy electric vehicles, now a different spectacle is gaining ground: humanoid robots walking the halls, demonstrations of “physical AI,” and wearable devices connected in real-time with driving, health, and safety data. The automotive industry, driven by electrification, software pressure, and fierce competition — especially from Asia — is expanding its ambitions: it no longer wants to just sell cars; it aims to operate platforms for mobility, automation, and applied intelligence.

The approach is industrial but also strategic. Manufacturers have been integrating sensors, connectivity, and assisted driving capabilities for years. The next logical step is to transfer that technological stack — cameras, lidars, edge computing, AI models, low-latency networks — to an adjacent domain: robotics. Fundamentally, a humanoid robot and a modern vehicle share part of their technological DNA: environmental perception, planning, control, and action in real environments with safety constraints. Just as vehicles have become “computers on wheels,” robots are beginning to present themselves as “autonomous machines with legs.”

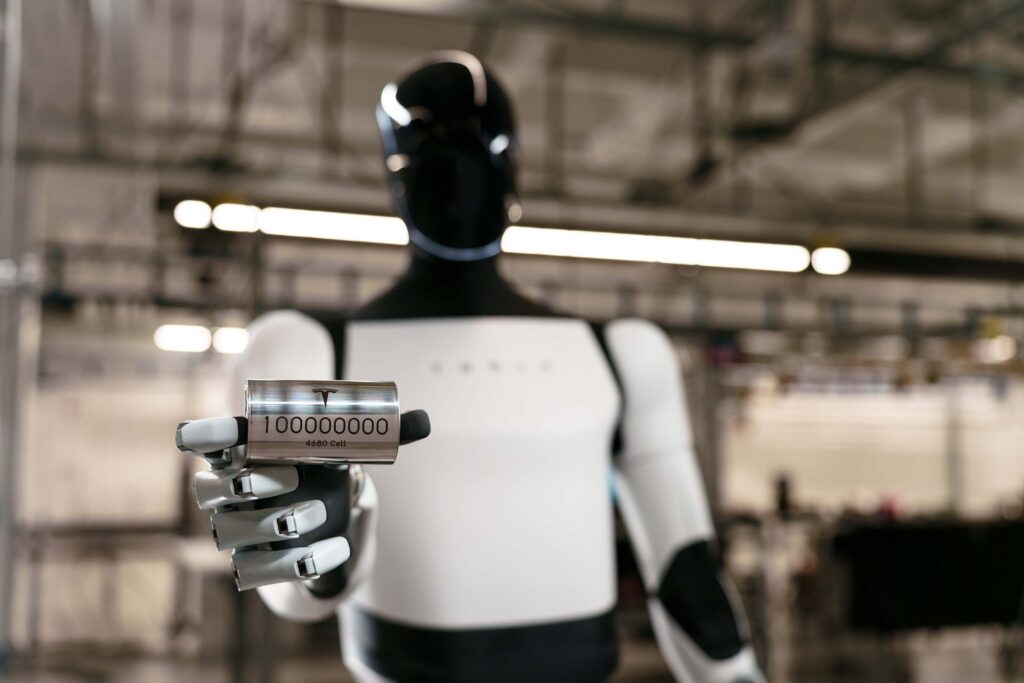

Humanoid robotics enters the assembly line

The most illustrative example of this convergence is Hyundai, which is using its subsidiary Boston Dynamics as a spearhead to bring humanoid robotics into industrial environments. At CES 2026, the company reinforced its “human-centered robotics” narrative and showcased progress with Atlas, a humanoid designed for factory tasks. The public plan aims to deploy Atlas in production facilities starting in 2028, with a roadmap to scale its use as safety and process stability impacts are validated.

The discussion is no longer whether robots will be in factories but what type of robot and for which tasks. In automotive manufacturing, where thousands of repetitive operations exist with a long history of automation, the humanoid offers an enticing idea: adapt to environments designed for humans (corridors, shelves, workstations) without completely redesigning the plant. In other words: introduce “robotic labor” into existing factories without reconfiguring them from scratch.

However, this leap also raises tensions. In South Korea, the debate over the labor impact of humanoids has already reached collective bargaining, precisely because large-scale deployment risks partial replacement in physical and internal logistics tasks.

Wearables: from gadgets to industrial devices

The other side of this expansion is the rise of wearables linked to industrial work and well-being. In 2026 tech events, manufacturers didn’t just talk about screens or voice assistants. They showcased worn devices that combine sensors, ergonomics, and data to reduce injuries and improve productivity.

Hyundai, for example, displayed the X-ble Shoulder, a wearable aimed at industrial environments to lighten shoulder load during repetitive tasks. The message is clear: automotive manufacturers don’t just want to automate; they also want to enhance human capabilities with lightweight exoskeletons and smart assistance. This ties into a specific business goal: reduce absences, improve safety, and sustain production amid aging workforces in several advanced economies.

Beyond factory environments, the connection between vehicle and wearable points to another direction: health, insurance, and digital services. Vehicles already measure braking, acceleration, and driver attention; wearables add biometric data (heart rate, stress, sleep) and physiological context. The potential result is an ecosystem where the car becomes an extension of the user’s “digital profile”: adaptive comfort, finer fatigue alerts, and — at the extreme — new product models and subscription services.

Car shows are no longer just about the vehicle

This shift has been especially prominent in Asia. The 2025 Shanghai Motor Show was interpreted by several analysts as a sign that competition is moving from mechanics and design toward embedded AI, connectivity, and automation. At the same time, CES 2026 reinforced the idea that the vehicle is just another node in a network of smart devices: robots, wearables, home, health, and factory.

This context also explains why semiconductor and architecture players like Arm are pushing the concept of “Physical AI”: AI that exits the cloud and operates directly on machines acting in the real world. For automakers, this narrative fits perfectly: it justifies investments in computing, sensors, and networks and opens new business avenues beyond just the sale of vehicles.

The bet: less dependence on the car cycle, more control over the “stack”

Behind the trend of robots and wearables lies a cold motivation: diversify revenues and reduce reliance on a cyclical and increasingly competitive automotive market. Electric cars have lowered entry barriers in some segments, and software has increased the value of the digital experience. In this landscape, those who control the “stack” — chips, networks, data, AI, and automation — will enjoy more defensible advantages than those competing solely on catalog and price.

The big unknown is the timing. Humanoid robots still need to prove scalability, overall cost, and operational safety, especially outside demos. Industrial wearables will need to demonstrate that their promises translate into measurable outcomes: injury reduction, real efficiency, and return on investment. Yet, the overall direction seems clear: automotive is shifting from just “motors industry” to industry of applied intelligence.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does “physical AI” mean in automotive and robotics?

It refers to AI systems that not only analyze data but also perceive their environment and act in the real world: advanced driver assistance vehicles, industrial robots, autonomous logistics, and connected sensors.

When will humanoid robots begin working routinely in car factories?

Some public roadmaps project initial industrial deployments starting around 2028, beginning with limited tasks (e.g., parts sequencing) and expanding as safety and stability are validated.

What is the purpose of industrial wearables in automotive?

Primarily to reduce fatigue and injuries in repetitive tasks, improve ergonomics, and increase task consistency. In some cases, they function as lightweight exoskeletons or smart mechanical assistance.

How do consumer wearables relate to connected cars?

They can complement vehicle data with biometric and physiological information for functions like fatigue detection, personalized alerts, adaptive comfort, and eventually health or insurance services.