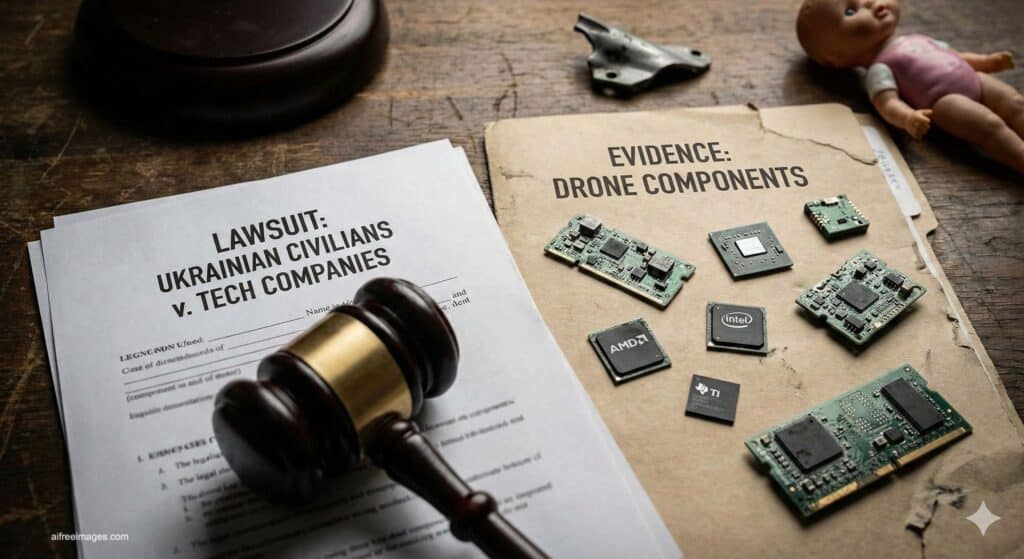

Five new civil lawsuits filed in Texas have once again brought up an uncomfortable reality of the Ukraine war: despite Western sanctions, technological components manufactured by major U.S. brands continue to appear in weapons used by Russia. The lawsuits, driven by Ukrainian civilian groups, accuse AMD, Intel, and Texas Instruments — as well as a distribution company owned by Berkshire Hathaway — of not doing enough to prevent their products from ending up in the hands of sanctions violators through reselling, intermediaries, and gray markets.

The phrase that has garnered the most headlines is from the lawyer representing the plaintiffs, who goes so far as to describe these companies as “merchants of death,” and also talks about “deliberate ignorance” or corporate negligence in curbing diversion.

What exactly are they acusying (and what not)

The core of these lawsuits is not accusing the companies of directly selling to Russia today — something that, in general, major American tech firms stopped after the February 2022 invasion — but arguing that their supply chain controls have been insufficient to prevent chips and components from being “reexported” by third parties and ending up in drones or missiles.

According to coverage by U.S. media, judicial documents cite incidents between 2023 and 2025 in which AMD and Intel parts have been found in weapon systems, including Iranian-made drones and cruise or ballistic missiles. The plaintiffs’ argument is that, if there is a repeated pattern, simply claiming “we comply with the law” isn’t enough: they say there should be evidence of reasonable measures taken to detect and cut off diversion attempts.

The “fourth actor”: the distributor connected to Berkshire Hathaway

Besides manufacturers, a significant focus is on the distribution channel. Recent reports mention Mouser Electronics as a company linked to Berkshire Hathaway through its corporate structure (Mouser is a subsidiary of TTI, which is part of the Berkshire ecosystem).

And here’s an important nuance for any “tech” reader: the component market doesn’t operate as a direct “manufacturer → military” sale. There is a global network of distributors, resellers, integrators, and brokers. Even when a manufacturer blocks a country, components can still circulate if someone purchases them in another region, resells, integrates into a product, and that product ends up where it shouldn’t be. That very gap (gray markets, re-exports) is what these lawsuits seek to turn into civil liability.

The corporate response: “We comply with sanctions,” but traceability isn’t perfect

The legal movement also raises a reputational issue. Coverage indicates that Intel has reiterated that it suspended shipments to Russia and Belarus at the start of the war and enforces similar standards for suppliers, clients, and distributors; while AMD and TI have previously defended their sanctions compliance (though, according to the published information, they had not provided new specific statements regarding these lawsuits at that time).

For the general public, the debate often seems binary: either the company “sold to Russia” or “did not sell.” But the legal narrative being constructed is more slippery: what level of diligence is required to prevent the diversion of general-purpose components (chips also found in PCs, routers, industrial systems, etc.) when opaque intermediaries, shell companies, and international resale chains are involved?

Implications for users, companies, and the sector (beyond the headlines)

- Increased regulatory and compliance pressure: if these lawsuits succeed, the practical standard could rise for “know-your-customer” (KYC) controls, red flag detection, and distributor audits. This would raise costs and potentially cause more friction in legitimate purchases—especially in B2B contexts.

- Reputational risk: the public doesn’t distinguish between “direct sales” and “diversion via third parties.” The public narrative punishes both equally. For mass brands like AMD, Intel, or TI, this erosion of trust matters—even if legally establishing liability is difficult.

- Indirect financial impact: lengthy lawsuits involve legal costs, uncertainty, and executive distraction. Plus, investors and insurers tend to scrutinize sanctions and export risks closely.

- Technological debate becomes politicized: the war turns “neutral” components (microcontrollers, FPGAs, SoCs, memories, etc.) into issues of business ethics and geostrategy. This ripples through the entire industry, from manufacturers to distributors.

In summary: these five lawsuits do not prove guilt on their own but reflect that the conflict is pushing the debate from “paper sanctions” to “real responsibility for diversion.” And in a world where a chip can travel farther than its end user, the clash between globalization and geopolitical control promises more developments ahead.

If you wish, I can prepare another version with a 100% financial focus (risks, comparable legal precedents, potential impact on margins/channels, and investor insights), or a more “cyber” version centered on gray markets, traceability, and supply chain.

via: tomshardware. Image generated with AI.