Fifty years later, the story feels like a movie: a California startup, still far from competing with giants, photos and “dismembers” a microprocessor of its future rival, rebuilds it using its own manufacturing process, and ends up Selling it to the military with astronomical margins. That bold move was the Am9080, AMD’s first CPU —a clone of the Intel 8080— which went into production in 1975 and, according to historical accounts, cost about $0.50 per unit and was sold for up to $700 to certain clients. This feat not only established AMD as a major player in the industry: it sowed the seed of a rivalry with Intel that would define the next five decades of personal computing.

A laboratory origin… and a photographic camera

The story begins in 1973, when Ashawna Hailey, Kim Hailey, and Jay Kumar — engineers who then worked at Xerox — decapsulated and microscopically photographed a preproduction Intel 8080. From about 400 micrographs, they created schematics and logic diagrams of the chip. With that functional “puzzle” in hand, they traversed Silicon Valley seeking someone willing to manufacture it.

AMD, founded in 1969 as a second-source semiconductor supplier and already familiar with nMOS technology, saw an opportunity. At that time, they had just developed their own n-channel process and needed a flagship product to demonstrate competitiveness. The Am9080 was perfect: pin-compatible and architecturally identical to the 8080, but with a smaller die design thanks to AMD’s process, enabling it to improve frequency and performance per area.

From “clone” to second source: the pact that avoided a legal war (and cemented the future x86)

The path of the Am9080 wasn’t without challenges. Cloning a leading microprocessor involved navigating a legal minefield. However, the context favored AMD: major institutional clients, especially in the military, demanded second sources to ensure supply continuity. These policies pushed Intel to sign a cross-licensing agreement in 1976 with AMD, in exchange for a payment that, according to historical records, totaled $325,000 ($25,000 at signing and $75,000 annually).

This agreement was crucial for two reasons. First, it regularized the status of the Am9080, which had begun its commercial existence in 1975 after a few shipments in 1974. Second, it laid the foundations of collaboration and competition that would later lead to the expanded agreement of 1982: the one that allowed AMD to manufacture x86 processors and launch its Am286 (a licensed version of the Intel 80286). Alongside these alliances, legal disputes would eventually arise; but the technical and commercial bridge was established.

Legendary margin: $0.50 cost, $700 price

If there was a “wildcard” that transformed AMD from an emerging supplier into a competitive contender with muscle, it was the margin of the Am9080. Manufacturing the chip in bulk, with smaller dies and good wafer yields (cited as ~100 units per wafer), kept the unit cost around $0.50. Selling each CPU for hundreds of dollars —up to $700 to military clients— gave AMD an unusual financial cushion for its growth phase: capitalizing on its process know-how and, simultaneously, funding its roadmap, equipment, and talent. This combination would be the launch platform to later compete in the PC market.

8080 architecture, DNA of the first great age of microprocessors

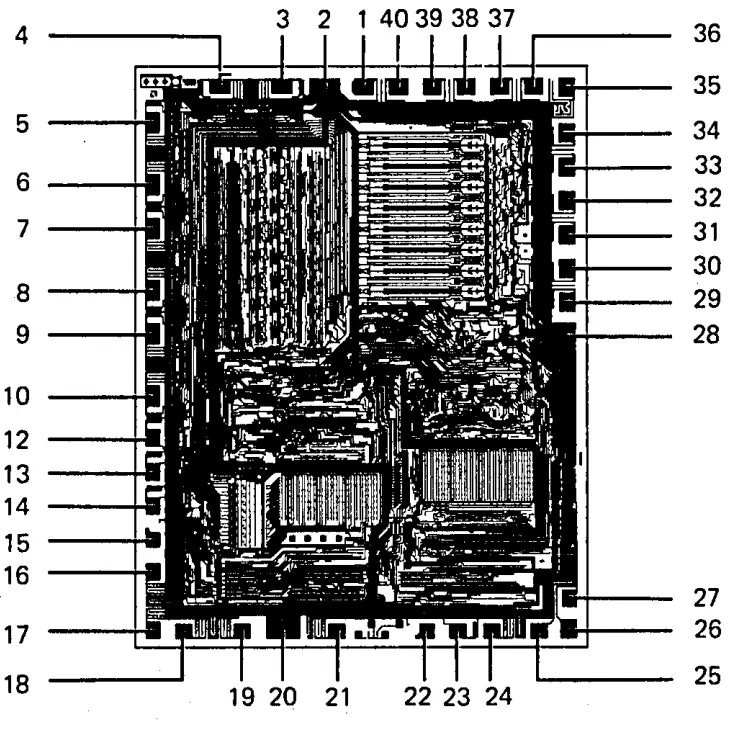

Technically, the Am9080 was an 8-bit microprocessor, ISA 8080, packaged in DIP-40 (also in ceramic variants CerDIP-40), fabricated in nMOS, with frequencies that, according to catalogs of the era, ranged from 2.083 MHz up to 4.0 MHz in the “-4” models. Although Intel did not usually exceed 3.125 MHz, AMD’s process allowed for higher clock margins in some versions.

The Am9080 family eventually included dozens of variants — 28 listed — including industrial and military models (MIL-STD-883) capable of operating from -55°C to 125°C, ideal for aerospace and defense. Alongside the CPU, AMD offered support chips such as the Am8224 (clock and driver), Am8228/8238 (controller/system and bus driver), and the Am8212 (8-bit I/O port), creating a platform for building scaled systems.

How to clone and improve a 8080?

The engineering behind the 8080 was well documented post-factum, but not at first. The team behind the Am9080 achieved this through pure reverse engineering: decapping the package, photographing the die, reconstructing masks and logics from micrographs (about 400 images), and redesigning for AMD’s own nMOS process. There was no — and could not be — literal copying of layout, but there was functional equivalence at the ISA and timing levels.

The advantage of nMOS for AMD was not minor. A smaller die reduces production costs and often improves slightly the speed and dissipation. That differential enabled launching versions at higher MHz and with various thermal sieves (commercial, industrial, military), broadening markets and contracts.

Second source: the industry’s safety net in the 70s

Why would a client pay $700 for a chip that was essentially a clone? The answer is supply security. In the 70s, large contracts — especially in defense — demanded second sources to prevent production halts if the main supplier faced issues. For Intel, the AMD alliance opened those doors; for AMD, it shielded it from lawsuits and conferred legitimacy with the most demanding clients. The Am9080 was not merely a product: it was proof that AMD could meet specifications, manufacture at scale, and respond with quality.

From 8080 to x86: the bridge to the PC era

The expanded agreement of 1982 between Intel and AMD is perhaps the most pivotal episode of this saga. From that point forward, AMD acquired the right to produce x86 processors, leading to the Am286 —its licensed version of the 80286— and, over time, a trajectory culminating in families like Athlon, Opteron, and, decades later, the current Ryzen/Epyc. It’s a direct thread: without the Am9080 and the trust it built with major clients, the leap to x86 would have been much more difficult.

The context: 1975, the year that forever changed personal computing

The Am9080 entered production in 1975, a watershed year: the microcomputing ecosystem started to resonate, kits like the Altair 8800 (based on 8080) emerged, developer communities blossomed, and microprocessors evolved from lab curiosities to the heart of commercial machines. For AMD, timing, cost, and reliability were critical; for the sector, having alternatives to the original supplier was a catalyst for adoption.

Lessons still relevant half a century later

- “Second sourcing” as a competitive advantage: in a world of supply chains under tension, clients appreciate diversity. Back then, mainly for military compliance; today, for resilience and geopolitics.

- Process matters: a more efficient node can provide cost benefits and better performance even if the design is identical. AMD proved this with nMOS in 1975; today, it’s evident with N5, N3, or N2.

- Pragmatic agreements: the cross-licensing of 1976 avoided years of litigation and allowed both to access key markets. Coopetition is a pattern that reappears in the semiconductor industry.

- Margins that finance vision: selling a product at extraordinary margins seeded capabilities that later enabled AMD’s technological independence.

What happened after the Am9080?

The Am9080 family expanded to include variants for different thermal ranges and frequencies (2.083–4.0 MHz) and support for MCS-80 ecosystems. Over time, this led naturally to the 8086, and after the 1982 agreement, to the Am286 and the rise of x86 as the PC standard. For AMD, the journey from that “clone” to competing head-to-head with Intel in servers and desktops remains one of the industry’s most remarkable trajectories.

Fifty years on, the story of the Am9080 serves as a reminder: sometimes, innovation begins by recreating what already exists, but it succeeds when it can manufacture it better, sell it better, and capitalize on the momentum to create its own. The “copycat” of the 70s is today one of the companies leading the pace of high performance and efficiency in modern computing.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly was the AMD Am9080, and why is it considered a “clone” of the Intel 8080?

The Am9080 was an 8-bit microprocessor compatible with the ISA 8080. AMD developed it through reverse engineering Intel’s 8080 (decapsulation and die analysis), achieving an architecturally identical chip, but fabricated in its own nMOS process, with a smaller die and versions at higher frequencies.

How could AMD sell the Am9080 for $700 if each unit costs about $0.50 to manufacture?

The combination of high wafer performance, nMOS process, and demand for second sourcing — especially in military contracts — enabled AMD to set high prices. That margin financed its technological and commercial expansion in subsequent years.

What role did the 1976 agreement with Intel play?

In 1976, Intel and AMD signed a cross-licensing deal that authorized AMD as a second source for the 8080, preventing infringement lawsuits. This framework was expanded in 1982 to include the x86 family, enabling AMD to produce the Am286 and, eventually, develop its own x86 CPUs.

What variants and temperature/frequency ranges did the Am9080 have?

It included 28 variants, with speeds from 2.083 to 4.0 MHz and thermal ranges from 0–70°C (commercial) to -55–125°C (military, MIL-STD-883 compliant). The typical package was DIP-40, including ceramic versions.

via: wikichip