With sharp irony—“forcing Delaware into the EU,” “Eurocorps invades Japan,” “naming Red Hat Le Chapeau Rouge”…— Spanish professor and executive Alberto P. Martí (Chair of the Industry Facilitation Group at IPCEI Cloud and VP of Open Source Innovation at OpenNebula) shook the European cloud community this week. His jab targeted those still clinging to the belief that OpenStack should be the cornerstone of a supposed European sovereign stack. After the joke, his core message was clear: “OpenStack is a good open-source project for those who need it, but if we’re talking about European technological sovereignty, let’s bet on European open-source alternatives”. And, to leave no doubt, he recalled his 2022 warning: “No European organization will have the capacity to maintain a fork long-term if non-European providers controlling the project turn their back overnight”.

Beyond tone, the publication reopens a highly strategic and uncomfortable discussion: Europe’s cloud consumption is increasing, but its control over the technology and providers enabling it is decreasing. According to Martí and other experts, merely dressing platforms in “open source” with governance outside the EU will not suffice. If Europe wants a cloud (and especially an edge) with technological sovereignty, it cannot rely on projects dominated by Big Tech.

A picture that doesn’t lie: more cloud spending, less European market share

The data within Europe’s own ecosystem is stubborn. The European cloud market (IaaS, PaaS, and hosted private cloud) has grown fivefold since 2017, reaching €10.4 billion in Q2 2022. But, at the same time, the combined share of European providers has fallen from 27% to 13%. The global convergence toward three US-based hyperscalers—AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud—is rapid, with no European actor close to their leadership on European soil. Today, the strongest European players—SAP and Deutsche Telekom—capture barely 2% of the market, followed by OVHcloud, Telecom Italia, and Orange, in more modest positions.

The dependency isn’t abstract. 41% of European companies already use cloud services, and 73% of those are highly dependent on them. In plain terms: personal data, cybersecurity, and legislation compliance are increasingly dictated by non-European providers.

Edge as opportunity (and as urgency)

The European Data Strategy projects that by 2025, 80% of data will be processed at the edge, near users and IoT devices. The Digital Compass 2030 sets a clear goal: 10,000 secure and climate-neutral edge nodes in the EU. This decentralized shift—distributed cloud, multi-provider, multi-site— opens a window to break inertia: leading the deployment, operation, and commercialization of this new infrastructure layer can give European companies a real competitive edge.

However, the edge also puts pressure on a telco sector already touched by this transition. Operators are expected to lead the deployment of this edge cloud by leveraging their 5G networks and extensive presence at proximity sites. Yet, many still rely on non-European proprietary platforms (e.g., VMware) or collaborate with hyperscalers in programs like AWS Wavelength for initial edge deployments in Europe. For Martí and other analysts, this is a Trojan horse: it creates unsustainable dependencies, relegates telcos to co-location with a brand, and chains Europe’s future edge to foreign technologies and roadmaps.

Sovereignty: from data… to software control

In Brussels, the conversation already includes digital sovereignty and “geopolitical Europe.” President Ursula von der Leyen summarized bluntly: “We’re no longer on time to replicate hyperscalers, but we are to achieve technological sovereignty in critical areas”. The priority: mastery and ownership of key technologies in 5G/6G, semiconductors, quantum… and certainly cloud and edge.

The logical consequence of that approach is that sovereignty isn’t just about data and regulation: it requires control over the software managing the infrastructure—those orchestration and management platforms that coordinate on-premises, cloud, and edge resources in the continuum. If Europe doesn’t develop and sustain its own open platforms for this purpose, its data economy future will again depend on external providers.

The trap of controlled open source outside the EU

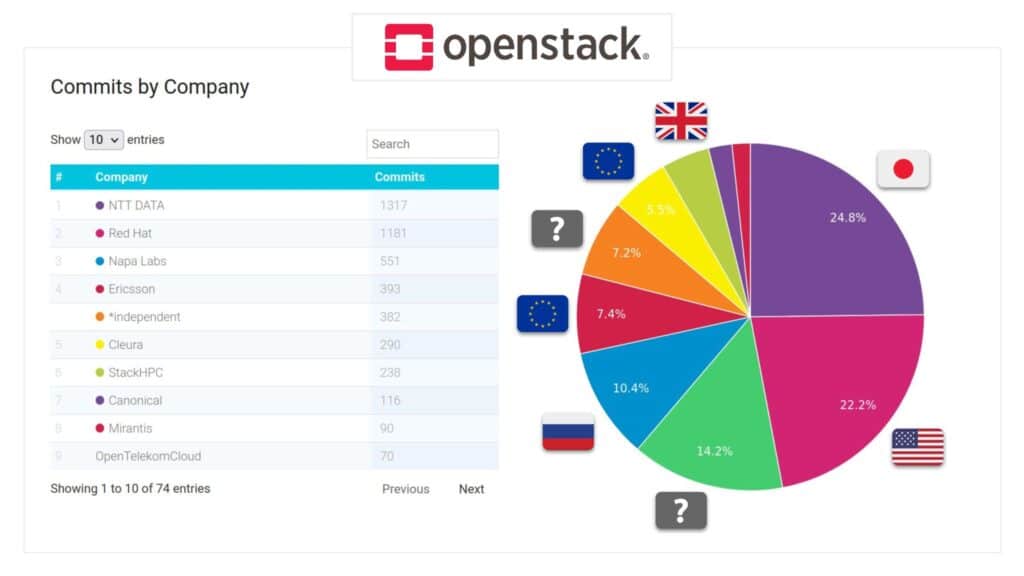

The Commission rightly promotes open source as a driver of competition, reducing lock-in, and digital independence. But “open source” doesn’t automatically mean “sovereign.” In reality, most of the open-source technologies used today to build cloud platforms are controlled by non-European entities. Martí points to OpenStack: a free project, valuable for many deployments; but governed by a Texas-based foundation (OpenInfra Foundation), with contributions dominated by Red Hat/IBM and other non-UE vendors, and a Board where only 5 of 27 members represent European organizations. The practical outcome: a complex platform whose steering responds to global roadmaps outside European strategy.

Making OpenStack the core of a “EuroStack” would create new dependencies: if tomorrow the biggest non-European contributors withdraw support, no EU entity could maintain a fork of that scale in the long run. This is the structural risk highlighted by advocates of a European stack: free licenses alone are not enough; governance, community, and industrial capacity are essential behind the code.

What is Europe doing (and what’s still missing)

On the policy front, initiatives are piling up:

- European Alliance for Industrial Data, Edge and Cloud: companies, member states, and experts craft an investment plan for next-generation cloud/edge technologies.

- IPCEI on Next Generation Cloud Infrastructure and Services (IPCEI-CEI/CIS): aims to build shared capabilities and European edge infrastructure, along with advanced data processing services over the datacenter-edge-cloud continuum.

- European Sovereignty Fund (announced): intended to strengthen industrial capacity and reduce technological dependencies.

All these efforts outline an ambition. What’s missing—sector voices emphasize—is an active role for European industry in developing and maintaining the open platforms that a sovereign edge requires; projects with EU governance, financed contributions, and aligned roadmaps in line with European strategy.

How to truly build a sovereign stack

There’s no shortcut, but there is a plausible roadmap:

- European governance of the code

Foundations or consortia with headquarters and jurisdiction in the EU; boards of directors with majority European representation; transparency in licenses, brands, and IP. - Funding and roadmap

Stable programs (beyond project-specifics) for core developers, QA, security response, and release engineering. Sovereignty demands the capacity to sustain these long-term. - Public procurement that drives the market

Include criteria for technological sovereignty in tenders (project governance, data compliance, roadmap, and support within the EU). No veto based on passport, but reward what promotes autonomy and resilience. - Telcos: from “proprietary first colocation” to edge operator

Replace proprietary dependencies with European open platforms; prioritize co-development and OSS community participation. - Skills and testbeds

Academies and labs with edge pilots—healthcare, mobility, energy—to train operators, SREs, and developers in the upcoming distributed model. - Certification and badges

Compliance schemes for providers demonstrating technological sovereignty (project governance, software supply chain, security, and auditing).

Risks to watch out for

- Fragmentation and “reinventing the wheel” via a thousand incompatible micro-projects.

- Sovereignty branding: dressing “EU-friendly” platforms governed outside the EU.

- Late arrival to edge: the 2025–2030 window won’t wait; hyperscalers are already moving pieces.

A debate that is now political… and operational

Martí’s post viralizes the issue with humor, but the thesis is serious: the EU must regain control of the software orchestrating its data economy. And this won’t be achieved by outsourcing that control to external foundations and steerings (even if the code is open); nor by trusting that a hyperscaler will voluntarily become “sovereign by delegation.”

If Europe strategically bets on the edge—decentralized, multi-provider, and legally compliant in Europe—the stack that governs it must also be open and European in its governance and sustainability. Here and now, not in five years.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the EU define “technological sovereignty” in cloud and edge?

It’s not just about where data resides. It’s the ability to decide and maintain control over key technologies (infrastructure and management software) under European standards, governance, and industrial capacity, reducing dependencies on outside providers.

Why isn’t OpenStack suitable as a pillar of a sovereign “EuroStack”?

Because, while it is open source, its governance and contributions are dominated by non-European entities; if support were cut tomorrow, Europe would lack the muscle to sustain a long-term fork. Dependence risks remain.

What European initiatives are underway to strengthen sovereign edge?

The European Alliance for Industrial Data, Edge and Cloud (investment plan) and the IPCEI Cloud (shared capabilities and edge infrastructure in the EU). Key targets: 80% of data processed at the edge (2025) and 10,000 secure and carbon-neutral edge nodes (2030).

What can telcos and administrations do now to promote open European alternatives?

Adopt sovereignty criteria in procurement, co-finance core devs for European OSS projects, migrate from proprietary platforms to open stack, and launch multisector edge pilots to build traction and skills across Europe.

Sources

- Dr. Alberto P. Martí, LinkedIn (post of the Chair of the Industry Facilitation Group at IPCEI Cloud and VP of Open Source Innovation at OpenNebula Systems, 4 days ago)—a satirical/serious reflection on OpenStack and European technological sovereignty. via: LinkedIn

- sovereignedge.eu — The birth of a geopolitical EU cloud industry – Reclaiming open source as a tool for Europe’s technological sovereignty— analysis of the European cloud market, hyperscaler dependency, edge role, telcos, and OSS governance (with references to Synergy Research, Eurostat, EU Cloud Alliance initiatives, and IPCEI).