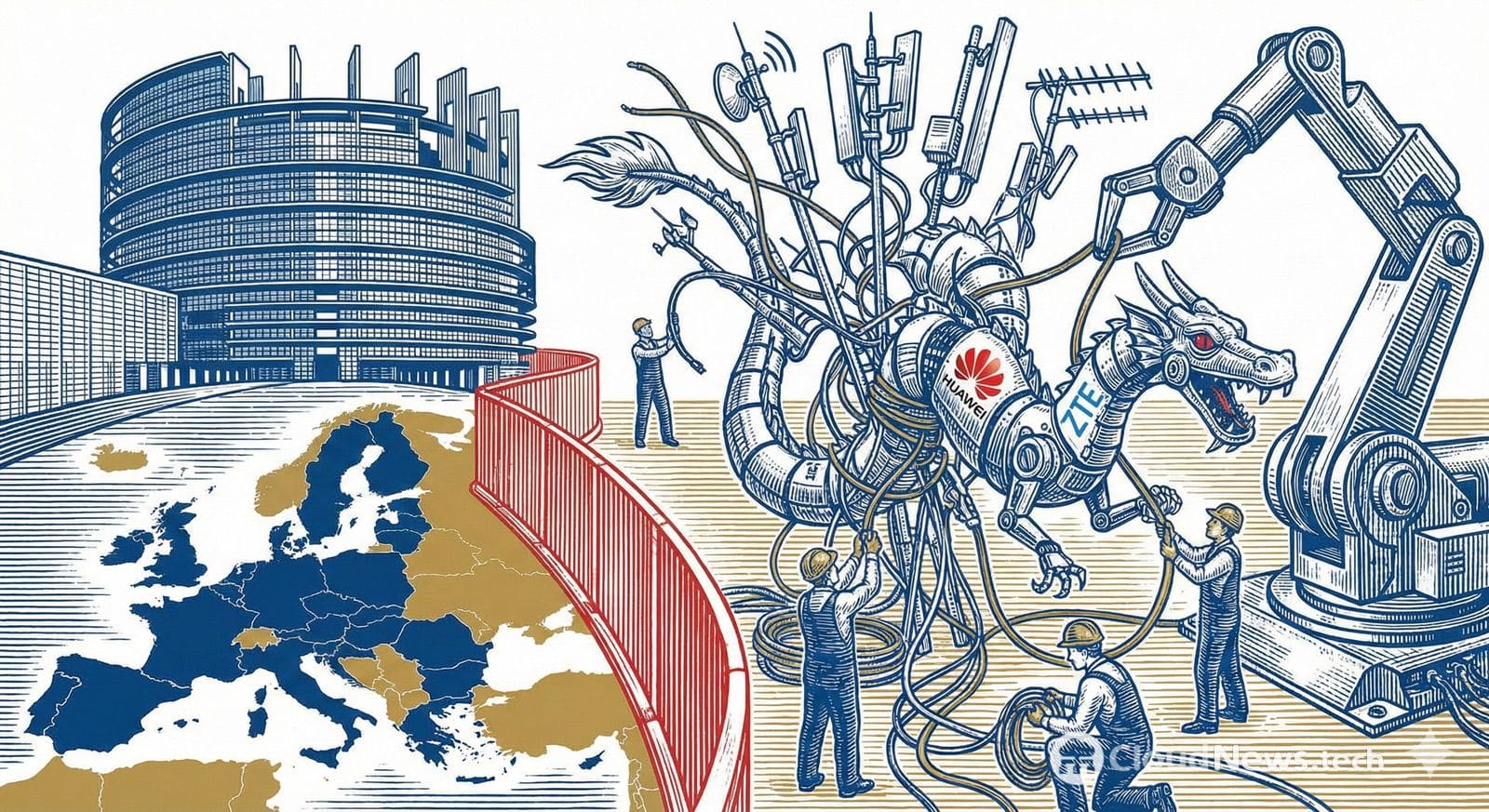

Brussels is about to take a step that, in practice, changes the rules of the game in a field where Europe has been advancing cautiously for years: the access of providers considered “high risk” to critical infrastructure. The European Commission is planning to present on Tuesday, January 20, 2026 a proposal to make mandatory—and not just voluntary—security measures that until now recommended to member states to limit or gradually eliminate equipment from companies such as Huawei and ZTE in sensitive sectors.

The initiative, according to recent information published, is not limited solely to telecommunications networks. The approach being considered in Brussels broadens the focus to other high-impact areas, such as systems related to the energy sector—including solar energy—in a context where the European Union is trying to reduce strategic technological dependencies under the “de-risking” approach.

From recommendations to obligations: the tipping point

Until now, the European framework for safeguarding 5G deployment and critical networks relied on an approach of guidance and coordination, allowing each country to modulate the pace and severity of restrictions. This flexibility has resulted in an uneven map within the EU: some states have hardened their stance against Chinese providers, while others have preferred to keep the door slightly open due to cost, deployment timelines, or diplomatic balance.

In 2023, the Commission had already raised its tone by deeming justified—and aligned with the European 5G cybersecurity toolkit—the decisions of certain countries to restrict or exclude Huawei and ZTE, highlighting concerns over the associated risks of certain suppliers in critical networks. The current novelty is the move from political pressure and technical recommendation to a more binding framework, with potentially uniform effects across the internal market.

Huawei: from market boom to network anchoring

The scope of the debate cannot be separated from Huawei’s accumulated industrial presence in Europe. The brand, which for years competed strongly in smartphones—until U.S. restrictions and sanctions affected its access to key technologies and services in the mobile ecosystem—also built up its network infrastructure business, where its equipment has remained an attractive option in terms of performance and price across various markets.

This legacy explains the delicate front opened by the European plan: removing or replacing already deployed technology is not a cosmetic operation. It involves redesigns, supplier switches, technical validations, stock availability, logistical planning, and ultimately impacts investments that operators amortize over several years.

Spain and Germany: the political tussle and the costs of “rip and replace”

The Brussels move comes with recent experience from countries where the debate has been particularly tense. Germany, for example, agreed in 2024 on a phased process to remove Huawei and ZTE components: first from the core of 5G with a deadline by the end of 2026, and later in peripheral layers with a longer timeline. This model illustrates the balance sought by governments: security and resilience, but without causing an abrupt cut that jeopardizes service continuity.

Meanwhile, pan-European operators have been adjusting their strategies as regulatory demands have tightened. Telefónica announced in 2025 that it was removing Huawei 5G equipment in Spain and Germany to comply with the regulatory frameworks of both countries, while maintaining use of the provider in markets without comparable restrictions. The industry’s clear message: when rules change, the supply chain reconfigures, even if at different paces depending on the geography.

Security, sovereignty, and a “dual” dependency

The proposal also comes at a time when the EU is trying to strengthen a political idea gaining weight in Brussels: it’s not just about reducing dependency on China, but about avoiding excessive reliance on any external actor, including major U.S. companies. This approach connects with the European agenda of technological sovereignty—and with market movements like the creation of “sovereign” cloud offerings for European clients—responding to increasing sensitivity around where data is stored, who manages the infrastructure, and under which jurisdiction services operate.

For the EU, the discussion around “high risk” providers is part of a broader strategy: enhancing supply chain security, limiting attack surfaces in critical sectors, and gaining more autonomy amid persistent geopolitical tensions.

China’s reaction: investment and accusations of protectionism

As expected, Beijing has responded publicly. On January 19, 2026, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs urged the EU to not damage Chinese companies’ confidence to invest in Europe, criticizing the move as a form of “protectionism” and calling for a “non-discriminatory” environment. This verbal clash signals that the discussion will not be purely technical: the measure may become a new point of friction in the Brussels-Beijing trade relationship.

What short-term changes might occur in the European market

If the proposal materializes into binding rules, impacts could be seen across several fronts:

- Operators and utilities: will need to adapt procurement and replacement plans, with timelines that could vary depending on the segment’s risk level (core, transport, access; or energy components).

- Provider competition: the role of “trusted” manufacturers in Europe will be reinforced, with the risk of greater market concentration if alternatives diminish.

- Costs and timelines: replacing critical equipment requires operational windows, testing, and compatibility checks. The sector fears that an overly aggressive schedule could strain budgets and deployment schedules.

- Systemic effects: critical infrastructure does not operate in “silos”; telecom, energy, and digital services are interconnected. Decisions in one sector can influence others.

For now, the key step is political: formal presentation, negotiation, and national implementation. But the underlying message is clear: Europe wants its critical infrastructure to become less dependent on external technological decisions and increasingly governed from within.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does it mean that Huawei and ZTE are “high risk” providers in the EU?

It implies that, based on security and risk management assessments in critical networks, their involvement may be considered particularly sensitive due to the level of exposure a failure, intrusion, or prolonged dependence on essential infrastructure could pose.

Will this measure affect 5G coverage or service quality in Spain?

The regulatory goal is typically to ensure a planned transition, avoiding disruptions. The most likely effect for end users is not an immediate service drop but changes in investment and modernization timelines, depending on how deadlines are set.

What alternatives are there to Huawei and ZTE in telecommunications infrastructure?

In Europe, the most common providers in mobile and backbone networks have been groups like Nokia and Ericsson, among others present in various segments. The strategic concern is to prevent the exit of one actor from leading to excessive dependence on a few suppliers.

Why is the EU including sectors like solar energy in the security conversation?

Because energy infrastructure increasingly incorporates connected electronics, telemetry, and control systems. In an environment of hybrid threats and cyberattacks, supply chain security and connected component safety are considered part of national and European resilience.