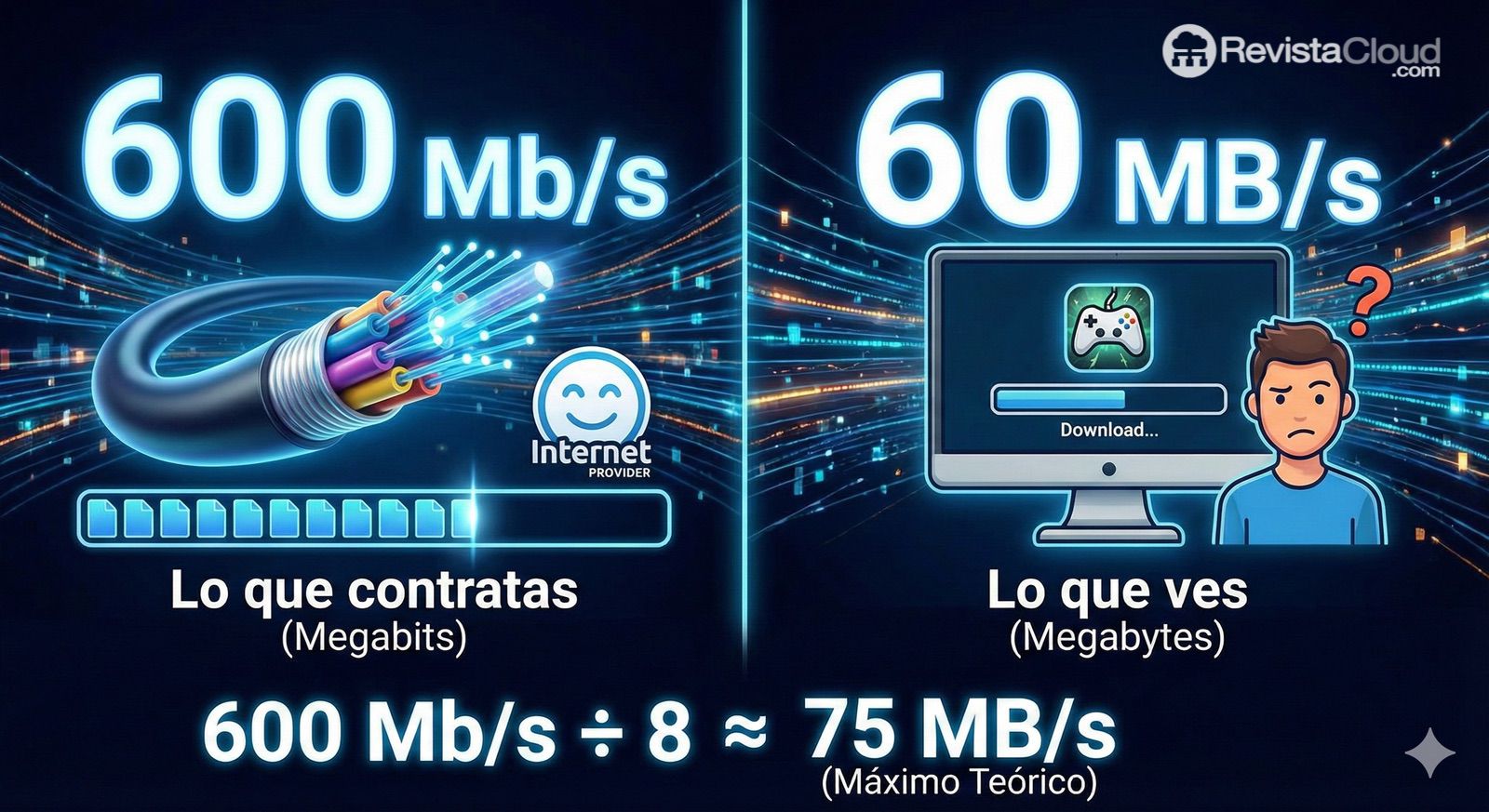

Sometimes, it’s not about the network going down, a faulty router, or your provider “throttling” anything—it’s simply the same phrase appearing in thousands of homes: “Internet is slower than what I was told”. This often happens at a very specific moment: when someone subscribes to a 300, 600, or 1,000 Mbps connection, starts a download, and sees numbers that seem too small. Frustration sets in quickly, but the explanation is usually much simpler than it appears: you are comparing different units.

In the telecommunications world, two measurements coexist that look very similar but mean very different things: megabits (Mb) and megabytes (MB). That visual similarity (a letter) is responsible for an widespread confusion—so much so that even many years of internet use won’t prevent people from mixing them up.

Mb and MB: two acronyms that look alike but aren’t the same

When a provider announces “600 megas,” they are actually referring to 600 megabits per second, or 600 Mbps. A bit is the smallest unit of information in computing and telecommunications, and traditionally (and by standard) the speed of a connection is expressed in bits per second: Kb/s, Mb/s, Gb/s.

However, when a user downloads a game on Steam, a file from a browser, or a system update, the device usually displays the speed in megabytes per second, or MB/s. A byte (B) is a larger unit, used for file sizes and memory: KB, MB, GB, TB.

The result is that two different measures are being compared as if they were the same, which causes the confusion.

- Megabit (Mb): a unit of transfer speed (what you contract for).

- Megabyte (MB): a unit of data size (what files occupy and what many downloads display).

The key rule: 8 bits = 1 byte

The core is a basic relationship in computing:

1 byte = 8 bits

Therefore:

8 Mb = 1 MB

This helps clarify many “mysterious speed losses.” Here’s a simple example:

- Contracted connection: 100 Mbps

- Theoretical maximum speed in MB/s: 100 ÷ 8 = 12.5 MB/s

That 12.5 figure is what users typically see during an ideal download (or something close to it). That’s why the feeling of being “lied to” happens so often:

- The provider advertises 100 Mbps

- The computer shows ~12 MB/s

It’s not that there’s a speed deficit: you’re viewing bytes, not bits.

Quick conversion: what it usually means in practice

To make the difference clearer, these conversions help set expectations. They are maximum theoretical values, before considering other factors:

- 100 Mbps → 12.5 MB/s

- 300 Mbps → 37.5 MB/s

- 600 Mbps → 75 MB/s

- 1,000 Mbps (1 Gbps) → 125 MB/s

This explains why someone with a “600 Mbps” plan might see downloads around 60–70 MB/s and think something is wrong, when in reality, it’s within the expected range.

Why maximum theoretical speeds are rarely reached

Even with a clear understanding of the units, another frustration appears: “Okay, I get Mb vs MB, but why can’t I reach 75 MB/s on a 600 Mbps line?”.

Because the contracted number represents the link limit, but part of that capacity is consumed by the network’s own operation. Data transfer involves unavoidable “overheads”:

- Headers and encapsulation: each packet carries control information (not just useful content).

- Transport protocols: TCP, for example, confirms receipt and manages flow to avoid losses.

- Retransmissions: if interference or packet loss occurs, data is resent.

- Congestion: if a segment is overloaded (Wi-Fi interference, limited router, congestion at the server or peering point), performance drops.

- Equipment limitations: an old PC, slow disk, or faulty cable can bottleneck performance, not the fiber.

That’s why, under normal conditions, a connection theoretically capable of 12.5 MB/s (at 100 Mbps) often achieves around 10–12 MB/s in practice—depending on circumstances. With 600 Mbps, seeing 65–75 MB/s during downloads is completely normal, especially with Wi-Fi involved.

Speedtest vs. actual download: two tests that tell different stories

Another common source of confusion is comparing a speed test with a particular download.

A speedtest is designed to measure your connection under optimal conditions: it often uses nearby servers, optimized routes, and multiple simultaneous connections to push the line to its maximum.

A real download, on the other hand, depends on many factors outside your control:

- The capacity of the server hosting the file (and whether it’s overloaded).

- The platform’s limits (e.g., download caps to distribute load).

- The network route to that server (sometimes with international hops).

- The number of concurrent connections and how the client manages the download.

- Wi-Fi stability or cable quality in the home.

It’s why you might see an excellent speed test result and, nonetheless, experience slower downloads from certain sites—no operator “throttling” involved.

How to tell if your connection is actually poor

Understanding Mb and MB helps avoid false alarms, but problems can still occur. If someone suspects their line isn’t performing as it should, there are simple signs and checks:

- Test via Ethernet cable (Wi-Fi is often the main culprit).

- Ensure the network card negotiates at 1 Gbps or higher.

- Repeat tests at different times—congestion varies.

- Download from reliable, fast sources (large repositories, platforms with good CDNs).

- Compare results across multiple testing services (not just one).

Often, the issue isn’t “Internet” itself but the domestic segment: outdated routers, Wi-Fi saturation, or devices incapable of sustained high speeds.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many MB/s is “600 megas” in real terms?

If “600 megas” means 600 Mbps, the theoretical conversion is 75 MB/s (600 ÷ 8). In real-world use, actual speeds may be slightly below depending on Wi-Fi signal, server load, and network overhead.

Why does my provider advertise Mbps and my PC shows MB/s?

Because providers measure transmission speed in bits per second (the network standard), whereas operating systems typically display transferred size in bytes per second, which is more intuitive for files.

What’s better for checking speed: speedtest or a download?

A speedtest estimates your line’s maximum capacity; a download reflects real usage, but depends on server and route. It’s best to combine both tests and use a wired connection when possible.

If my wired connection is fast, but Wi-Fi is slow, am I being cheated out of fiber?

Not necessarily. Wi-Fi can be the bottleneck due to interference, distance, walls, channel saturation, or router limitations. The fiber line might be perfect; Wi-Fi performance is another matter.