By 2026, it will have been ten years since DE-CIX launched its neutral exchange point in Madrid, an infrastructure that, along with ESPANIX, has become a key piece of network interconnection in Spain. However, traffic patterns from recent years tell a striking story: the explosive growth after the pandemic seems to have plateaued, with occasional high peaks, but no clear upward trend.

Far from being a mere anomaly, this behavior sparks a technical and market debate affecting operators, content providers, CDNs, and companies relying on connectivity to operate: are neutral exchange points losing influence, or is the way internet traffic flows simply changing?

A repeated peak, but an average that remains steady

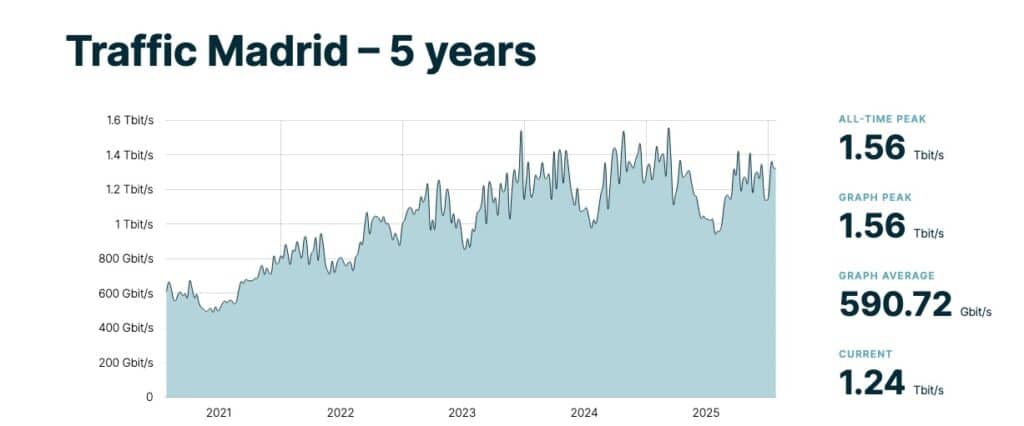

DE-CIX Madrid’s graphs over five-year and one-year windows reveal two simultaneous realities. On one hand, the exchange reaches top-tier figures: the “all-time peak” hits 1.56 Tbit/s, and the “current” traffic hovers around 1.24 Tbit/s at the time captured by the statistics. On the other hand, looking at the bigger picture, the dominant signal is stabilization: the five-year average is 590.72 Gbit/s, while the last year’s average rises to 727.51 Gbit/s, but with fluctuations that do not establish a sustained growth trend.

Practically speaking, this aligns with early market signals: Madrid has grown as a hub for interconnection and data centers, but traffic doesn’t necessarily have to “pass through” the neutral exchange point for the country’s connectivity to improve. It could actually be the opposite — that connectivity enhances precisely because traffic is taking more direct routes.

Explaining the traffic “ceiling”: less public transit, more private routes

There is a structural reason why a neutral exchange point might stop growing even as data consumption increases: an increasing share of traffic is resolved outside the public exchange.

In practice, a significant part of video, social media, and bulk downloads no longer depends heavily on traditional public peering but instead relies on a combination of:

- Private interconnections (PNI) between major networks (operators, hyperscalers, content platforms).

- Embedded caches within networks (CDN servers deployed in central sites and metropolitan nodes), which prevent traffic from “exiting and re-entering” through a neutral exchange.

- Multi-CDN and edge strategies that bring content closer to end users and reduce the need for single-location exchanges.

The result is counterintuitive: neutral exchange points remain critical for resilience, route efficiency, and ecosystem openness, but their most visible metric (total throughput) doesn’t always grow at the same pace as consumption.

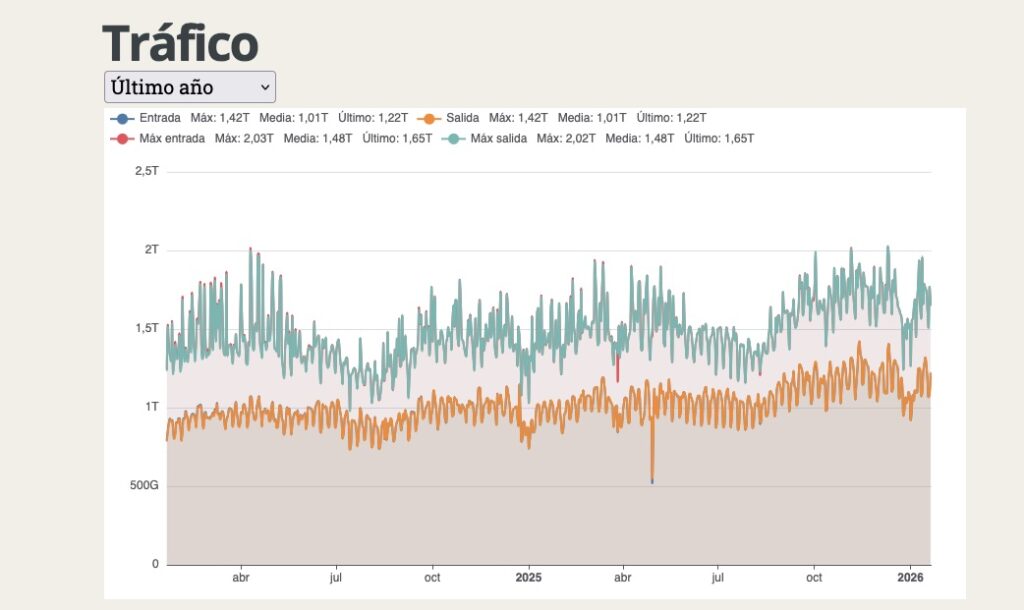

Contrast with ESPANIX: higher peaks, but a similar maturity trend

The ESPANIX graphs show an even greater exchange volume, with peaks of around 2.03 Tbit/s and high average values, reaffirming its role as a leading infrastructure in the country. Yet, the underlying message remains similar: Spain now has a mature interconnection ecosystem where growth is distributed among neutral exchange points, private links, and caching deployments.

In fact, the market has long observed that ESPANIX’s “switched traffic” exceeds 2 Tbit/s during peak demand moments, underscoring the true scale of national exchange, even though internet topology no longer relies solely on public peering.

The blackout as a stress test: when traffic drops due to non-digital events

A recent event helps interpret some anomalous drops: the major blackout on April 28, 2025, which affected Spain and Portugal, cascaded to access networks, powering equipment, and connectivity services. During such events, not only is the electrical grid affected, but also mobile base stations, fiber gear, and distribution nodes, leading to a visible decline in total traffic.

These episodes are relevant because, paradoxically, they highlight the importance of neutral exchange points and data centers with robust contingency plans (energy, redundancy, 24/7 operations). It’s not just about “moving many gigabits,” but about maintaining routes, sessions, and critical services when physical infrastructure is compromised.

What this means for Madrid: less “flow growth,” more ecosystem competition

Celebrating ten years of stabilized traffic doesn’t mean technological stagnation. Instead, it signifies that DE-CIX Madrid has entered a mature market phase, where competition is driven by other factors such as:

- Network density and ease of peering agreements

- Added capacity and operational quality (redundancy, maintenance, provisioning times, support)

- Hub effect: proximity to major data center campuses, availability of metropolitan fiber, and presence of global providers

In this context, the “success” of a neutral exchange point is no longer measured solely by cumulative traffic growth, but also by how much it helps make local internet cheaper, faster, more resilient, and offers more interconnection options for small and medium networks.

Comparison table with key metrics from the graphs

| Indicator (from provided captures) | DE-CIX Madrid | ESPANIX (last year, capture) |

|---|---|---|

| Historical peak / maximum observed | 1.56 Tbit/s | 2.03 Tbit/s (peak entry) |

| Five-year average (long window) | 590.72 Gbit/s | — |

| One-year average (short window) | 727.51 Gbit/s | 1.48 Tbit/s (max “average” in capture) |

| Current value in panel | 1.24 Tbit/s | 1.65 Tbit/s (latest “max”) |

| Recent trend signal | Stabilization with peaks | Higher volume with seasonal oscillations |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an Internet exchange point (IXP), and why does it remain relevant despite the growth of private peering?

An IXP is an infrastructure where multiple networks efficiently exchange traffic. While private peering and caches have grown, IXPs are still essential for improving routing, reducing transit costs, and enabling interconnection with many networks without negotiating dozens of individual links.

Why might an IXP’s traffic “stop growing” even as internet usage increases yearly?

Because an increasing share of traffic is delivered via caches within operators or direct private links between large networks. In other words, traffic exists but doesn’t necessarily pass through the public exchange point.

What are the implications for companies and operators when DE-CIX Madrid reaches a plateau?

This indicates that the value shifts toward the quality of the ecosystem: number of connected networks, ease of peering, operational resilience, and proximity to data centers. For companies, this often translates into more options to optimize latency and costs, even if the total throughput doesn’t grow linearly.

How do major events (sports, premieres, live streams) impact traffic spikes at neutral exchange points?

Peaks typically correlate with mass consumption of OTT video and simultaneous broadcasts. During these times, local and regional interconnection capacity becomes critical to avoid congestion and longer routing paths.

References: bandaancha, De-cix, and Espanix