Any digital project starts simply: an application, a database, and a server that “holds up.” The problem arises when the product is functioning. Users increase, transactions grow, tables expand, and without warning, classic symptoms appear: pages that load slowly, queries that drag on, bottlenecks during peak hours, or outages that force hurriedly restarting services.

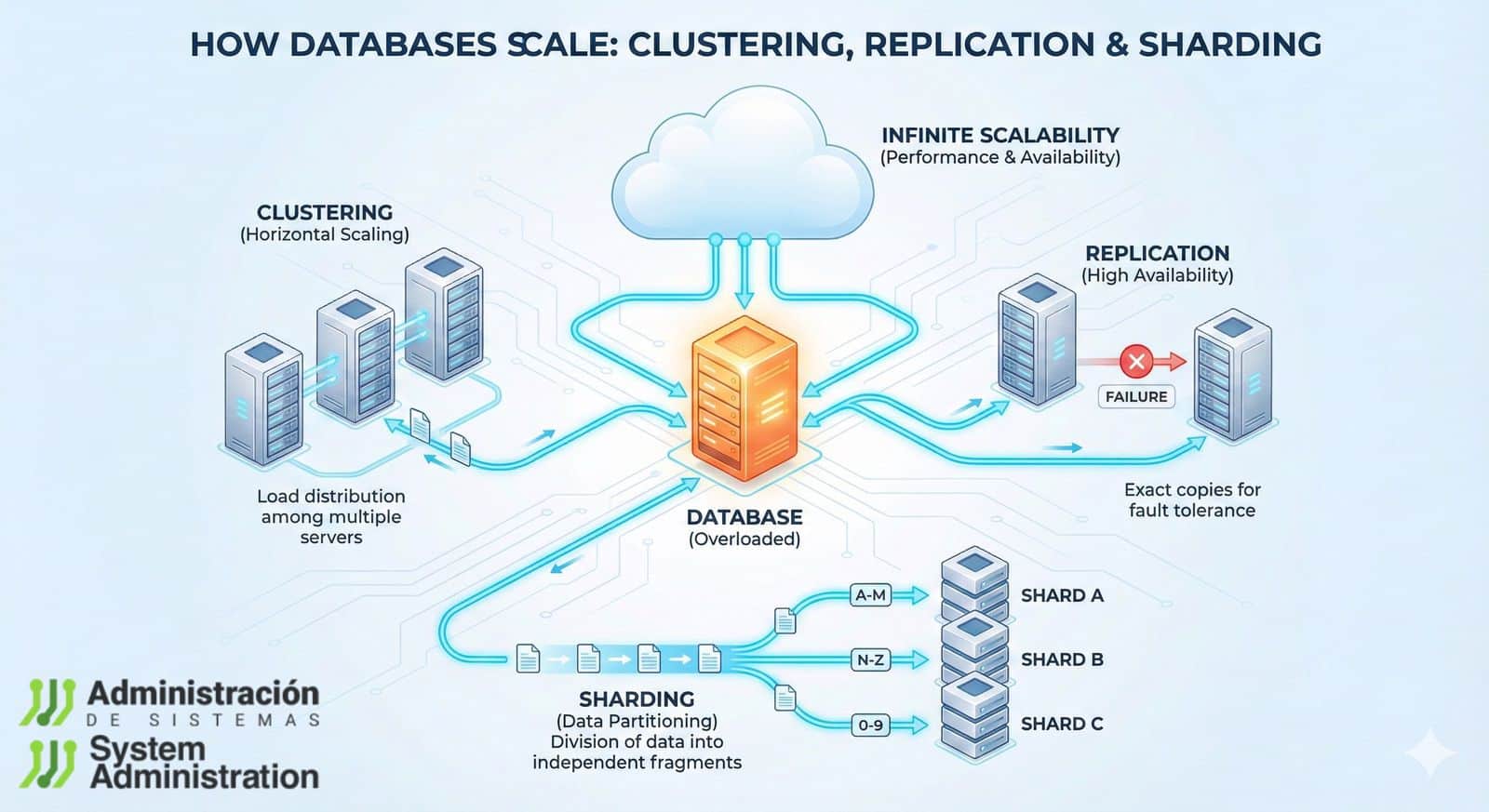

At this point, the question shifts from “What hardware should I buy?” to a more strategic one: How do you design a database that can grow without becoming a bottleneck? This is where three techniques that recur in nearly every modern architecture come into play: clustering, replication, and sharding. They are different approaches aiming for the same goal: distribute load, increase availability, and prevent a single server from bearing all the weight.

This article explains these ideas in a practical and generic way, applicable to most database engines and environments (on-premise, public cloud or private cloud, VPS, dedicated servers, or hybrid infrastructure).

What does “scaling” a database mean

Scalability is a system’s ability to handle more work without losing performance. This “more” can be:

- more concurrent users,

- more stored data,

- more requests per second,

- more writes (high transactions, updates, changes),

- or more reads (queries, reports, browsing).

In databases, there are two main paths:

- Vertical scaling: enhancing the server (more CPU, more RAM, faster disks).

- Horizontal scaling: adding servers and distributing responsibilities.

Clustering, replication, and sharding are horizontal strategies: they don’t just make a single server “bigger,” but rather build a system capable of growing by adding parts.

Clustering: when uptime is the top priority

Clustering connects multiple nodes so that the database remains available even if one fails. The core idea is high availability: if a server fails due to hardware, network, or software issues, another takes over.

Simply put, a cluster aims to:

- Minimize downtime,

- Automate failover,

- and ensure operational continuity.

Common clustering models

- Active-passive: one primary node handles requests, while others remain on standby. If the primary fails, the secondary is promoted.

- Active-active: multiple nodes handle load, coordinating to avoid conflicts. Requires more design and consistency management.

- Shared-nothing (no shared resources): each node has its own compute and storage, reducing dependencies and facilitating growth.

What it provides (and what it doesn’t)

- Provides: resilience, continuity, fault tolerance.

- Does not always provide: automatic performance improvements. Often, a cluster improves availability more than speed.

Clustering is typical in systems where “downtime cannot happen”: payments, reservations, critical operations, regulated environments, or 24/7 services.

Replication: live copies for faster reads and peace of mind

Replication involves maintaining one or more copies of the database synchronized with a primary server. In the classic setup, the primary node handles writes, and replica nodes serve reads.

This enables:

- Distributing read load,

- Redundancy in case of failures,

- Easier incident recovery,

- And, in some cases, bringing data closer to different regions.

How it works practically

- Primary: receives writes (INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE).

- Replicas: receive changes from the primary and respond to queries (SELECT).

Types of replication (which change how the system behaves)

- Synchronous: write is confirmed only when it’s also in the replica. Enhances consistency but may increase latency.

- Asynchronous: replica updates with delay. Faster, but introduces “lag,” meaning reads may be slightly out of date.

- Single primary / multiple replicas: the most common pattern for web applications.

- Multi-primary: multiple nodes accept writes. Can be powerful but requires conflict management and careful design.

Replication is not the same as backup

- Backup: a point-in-time snapshot for restore.

- Replication: a continuous flow of changes, aiming for availability and performance (especially reads).

Replication is often the first realistic step when a project grows—it’s implemented before sharding because it’s usually easier to operate.

Sharding: splitting the database into “chunks” for real scaling

Sharding (fragmentation) divides data into multiple separate databases called shards. Each shard contains only a part of the total data. Instead of one server holding everything, several servers store different pieces.

The main advantage is that it can scale reads and writes because it distributes work among shards. It’s the technique most associated with “massive growth.”

What this entails in practice

- Data is distributed based on a shard key (e.g.,

user_id, region, date range). - Each shard functions as an independent database.

- The application (or an intermediate layer) must know which shard to query.

Common ways to distribute data

- Range-based: e.g., users 1–1,000,000 in one shard, 1,000,001–2,000,000 in another.

- Hash-based: a function distributes users more evenly to avoid “hotspots.”

- Directory-based: a routing table indicates where each dataset resides (more flexible but adds operational complexity).

Why the shard key matters so much

Choosing a poor shard key leads to the worst case: one shard becomes saturated while others remain empty. Picking wisely means:

- Balanced distribution,

- Predictable queries,

- Easier growth by adding shards.

Sharding has the greatest potential—yet also the highest demands: careful design, testing, observability, and operational procedures.

Clustering vs. replication vs. sharding: what each is for

Though sometimes mentioned as “alternatives,” they solve different problems in practice:

- Clustering: prioritizes availability and failover.

- Replication: emphasizes redundancy and read scalability.

- Sharding: enables true horizontal scaling of data and load (including writes).

They are not mutually exclusive; rather, they complement each other.

Why modern applications need these techniques

As an app grows, the database is often the first major bottleneck. The reason is simple: it concentrates state, consistency, and transactions. Falling behind means the whole system slows down.

These techniques help achieve four common objectives:

- High availability: continue running despite failures.

- Low latency: quick responses under real demand.

- Reliability: consistent, protected data.

- Growth without downtime: scale without re-engineering the system every six months.

Costs and challenges not to overlook

Scaling a database isn’t just “adding nodes and going.” It introduces complexity:

- Consistency: especially with asynchronous or multi-primary replication.

- Operation and maintenance: upgrades, schema changes, backups, recovery testing.

- Observability: detecting which shard or replica is experiencing issues requires solid metrics and traces.

- Sharding adds extra logic: cross-shard queries, global aggregations, distributed transactions, data migrations become more difficult.

The usual recommendation in real environments is to proceed gradually and avoid sharding until truly necessary.

When to use each approach

- Clustering: when downtime is unacceptable and automatic failover is needed.

- Replication: when read load increases, redundancy is required, or analytical/BI workloads need isolation from main traffic.

- Sharding: when data size or write load exceeds what a single server can handle, even with good hardware and optimization.

Many systems start with replication, add clustering for availability, and only introduce sharding if growth demands it.

Combining techniques: the pattern of large systems

High-traffic architectures often feature layers:

- Sharded data by user or region,

- each shard with replicas for reads,

- and configurations with high availability to tolerate failures.

This combination provides performance and resilience at the cost of more sophisticated operation.

Best practices to start safely

- Optimize the essentials first: indexes, queries, connection pools, caches, engine and storage configurations.

- Introduce replication before sharding: often yields quick results with less complexity.

- Test failover and recovery: it’s not enough to “have a replica”; you must rehearse the day the primary fails.

- Plan schema changes: in replicated or sharded systems, deploys must be backward-compatible.

- Monitor lag, locks, and query times: performance is decided in small details that add up.

Conclusion

Clustering, replication, and sharding are three responses to an unavoidable reality: as data grows, a single database on one server hits a limit. Clustering protects availability, replication distributes reads and adds redundancy, and sharding opens the door to scaling without relying on increasingly larger machines.

The key is applying each technique when appropriate, gradually, measuring impact, and understanding operational costs. Scaling well means designing an architecture that enables growth with stability—not necessarily the most complex setup.

FAQs

What’s the practical difference between replication and clustering in a database?

Replication creates data copies (usually for reads and redundancy). Clustering prioritizes high availability with failover and node coordination, though it can leverage replication depending on the engine and design.

When does replication truly benefit a website or app?

When the system becomes read-heavy: many queries per user, listings, searches, catalogs, or content with constant traffic. Replicas lighten the load on the primary.

What signs indicate a database needs sharding?

Sustained growth in size, I/O saturation, increasing write times, frequent locks, and limitations that persist even after optimizing queries, indexes, and hardware.

Can sharding be implemented without changing the application?

In many cases, not entirely. Sharding usually requires routing logic (knowing which shard to query) or an intermediary layer that manages it. The more complex queries are, the more important it is to plan that part carefully.