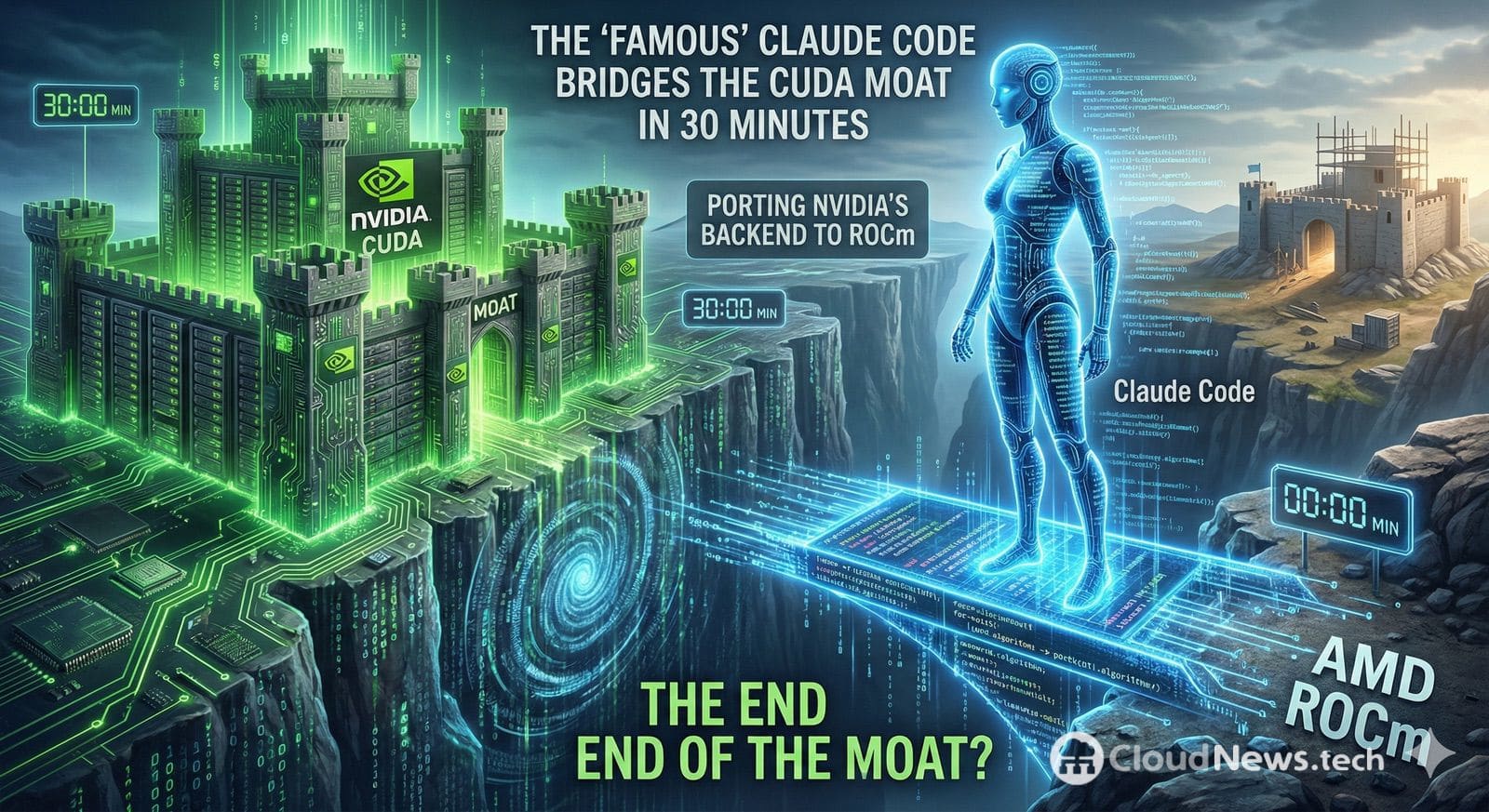

A thread on Reddit has sparked a discussion that’s been simmering in the GPU community for months: to what extent is the “CUDA wall”—the combination of APIs, libraries, tools, and accumulated expertise around NVIDIA—still a real barrier if agent-assisted programming tools begin to automate the hard work of porting?

The origin of the buzz is a statement as direct as it is controversial: a user claims to have ported a complete CUDA backend to ROCm in about 30 minutes using Claude Code, Anthropic’s agent-based coding environment, without resorting to “intermediate” wrapper layers, with only one significant hurdle: differences in data layout.

Why This Matters: ROCm Isn’t New, but the “Exit Cost” Could Change

AMD has been pushing ROCm as an GPU compute platform for years, relying on HIP, an approach designed to make parts of CUDA code portable with reasonable changes. AMD also offers official tools like HIPIFY to automatically convert CUDA source code to HIP C++.

The practical issue is that “porting” is rarely just about compiling: it involves maintaining correctness (getting identical results), recovering performance (or minimizing losses), and replacing dependencies (such as specific CUDA libraries). That’s where organizations encounter reality: the cost isn’t just technical—it includes testing, performance profiling, regressions, and ongoing maintenance.

If an agent-based tool drastically reduces the initial translation time, the debate shifts from “is it possible to port” to “how much effort is needed to validate and optimize the port” and “how many cases remain outside automatable solutions.”

What We Know About the Case: Viral Claim and Real PR

On Reddit, the user links their experience to a concrete work: a pull request in the Leela Chess Zero (lc0) repository titled “full ROCm backend.”

This detail is significant because it separates two levels:

- Verifiable Level: A public PR introduces a ROCm backend in a real project.

- Debatable Level: The claim “I did it in 30 minutes with Claude Code” depends on the author’s testimony and the exact context (size of code, kernel complexity, functional coverage, tests, etc.).

In other words: there’s a tangible piece of technology, but the conclusion that the “CUDA wall is down” is currently more an emotional headline than a universal demonstration.

Why an Agent Can “Port Quickly”… and Why That Doesn’t Kill CUDA

Agent tools are especially well-suited for mechanical transformation tasks:

- Mapping common CUDA calls to their HIP/ROCm equivalents where possible.

- Renaming types, macros, and utility functions.

- Restructuring files, CMake configurations, and build flags.

- Systematic refactoring that previously required hours of repetitive work.

This aligns with what AMD accomplishes with HIP/HIPIFY: automating the most “editorial” part of porting.

And Claude Code, designed to work with repositories and development tasks, emerges as a tool capable of executing extensive changes with the help of an agent.

However, the “CUDA moat” isn’t just about function names. The failure of the “port in minutes” promise occurs in work that is not purely syntactic:

- Hardware-specific optimization

High-performance kernels are tightly linked to cache hierarchies, access patterns, occupancy, synchronization, and micro-decisions that don’t always translate easily across architectures. - Semantic and execution differences

Even when platforms look similar, small behavioral differences or assumptions can produce subtle bugs that only surface under load, with specific input sizes, or in concurrent scenarios. - ecosystem dependencies

CUDA isn’t just the runtime—it includes libraries, profiling tools, documentation, examples, and a huge installed base. Porting a serious project often involves replacing or revalidating auxiliary components. - Validation and maintenance

The real costs appear afterwards: CI, performance testing, numerical tolerances, regressions, and the business question: “who maintains this portable branch when upstream evolves?”

The Real Impact: Lower Entry Barriers But Not “End of Lock-in”

What would change—if these cases multiply—is the psychology of the market:

- For teams considering multi-vendor GPUs, lowering initial porting costs reduces the fear of vendor lock-in.

- For AMD and its ecosystem, each story of “quick migration” becomes organic marketing and competitive pressure.

- For NVIDIA, the risk isn’t CUDA disappearing but part of the market starting to treat CUDA as just another target rather than “the only reasonable path”.

Nevertheless, calling it the “end of the wall” is premature. The barrier isn’t just technical; it also involves training, mature tooling, dominant libraries, support, and talent pool.

Broader Industry Context: Cracks in the Wall for Months

This episode comes amid growing initiatives (with different approaches) to reduce dependency: from compatibility layers to community projects aimed at executing or adapting CUDA workloads outside NVIDIA. A recurring example in the debate is ZLUDA, a project targeting CUDA compatibility on non-NVIDIA environments.

The key difference now is the “agent factor”: if a model can handle the repetitive work, while humans focus on validation and tuning, the cost equation shifts.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is ROCm and how does it differ from CUDA?

ROCm is AMD’s platform for GPU computing, with its own compilation stack and runtime. CUDA is NVIDIA’s proprietary platform. AMD promotes HIP as a way to write more portable code across GPUs, while CUDA is optimized for NVIDIA’s ecosystem.

Does HIPIFY allow “automatic” CUDA porting?

HIPIFY automatically translates parts of CUDA source code into HIP C++, helping accelerate migration. However, it doesn’t guarantee full functional equivalence or identical performance; those steps require testing and fine-tuning.

Can Claude Code replace HIPIFY or a development team?

It can speed up repetitive tasks (mass refactors, API changes, build adjustments), but complex projects still rely on validation, debugging, and performance tuning. Result quality also depends on context, available tests, and human review.

What should a company do to reduce dependence on CUDA?

Typically: identify “portable” components (custom kernels), separate dependencies, build a suite of tests and benchmarks, and treat porting as an engineering project with KPIs (correctness and performance). Automated tools can cut time but don’t replace robust technical governance.