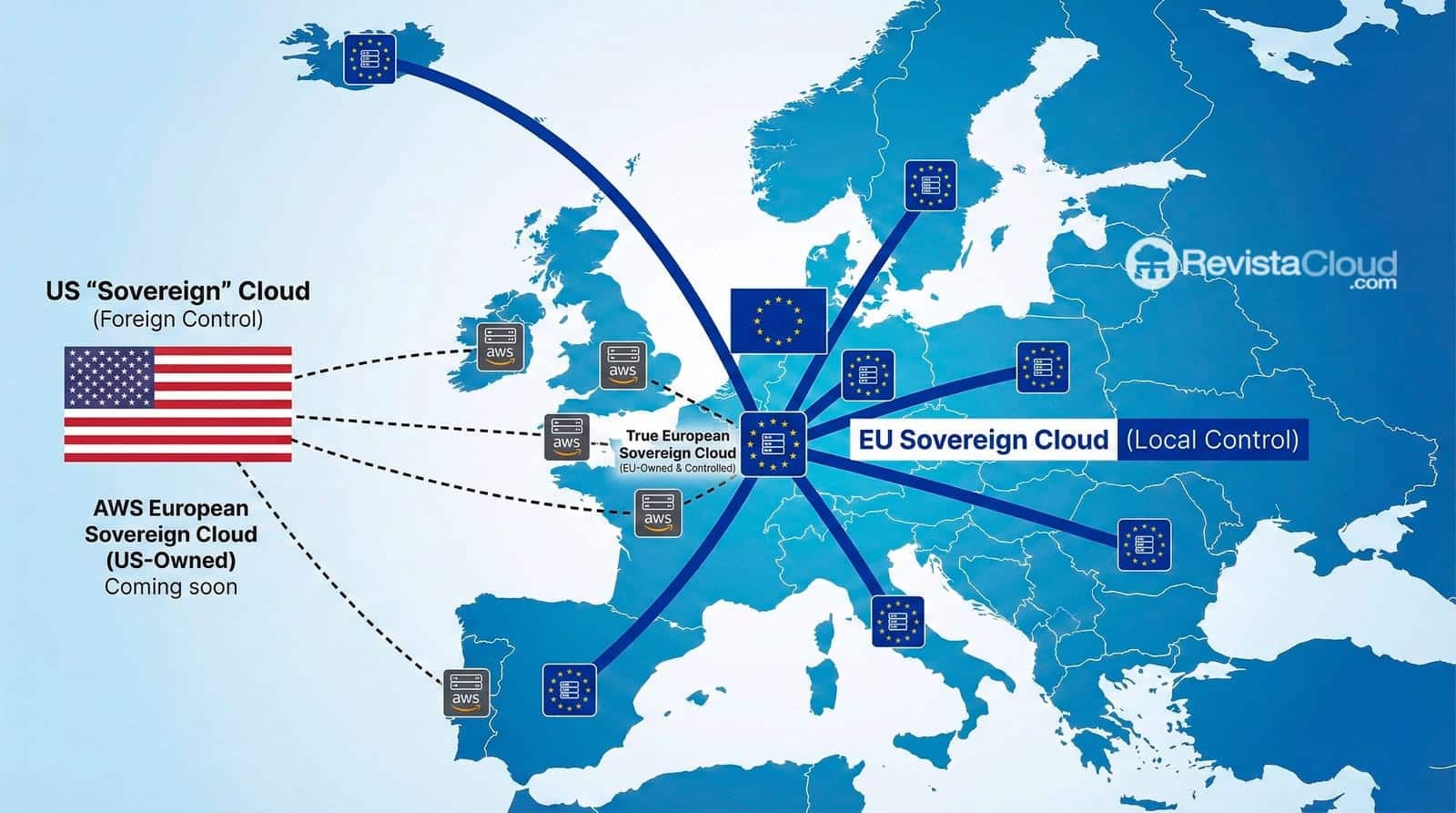

In Amazon Web Services (AWS)’s new data center map, there’s a prominent label over Germany: “AWS European Sovereign Cloud – Coming soon”. The promise is enticing for governments and regulated businesses: a “sovereign” cloud for Europe, managed by European personnel, with data residing within the Union and designed to comply with GDPR, NIS2, and the rest of the EU regulatory framework.

However, behind the slogan, an uncomfortable question arises:

Can infrastructure controlled by a U.S.-based company truly be sovereign for Europe?

The answer, given the current legal and geopolitical landscape, is simple: no. Or at least, not in the strong sense of sovereignty that many public officials and regulators claim to pursue.

What AWS Promises: Physical Separation, European Personnel, Major Investment

AWS details that its European Sovereign Cloud will be an “independent” cloud for Europe: physically and logically separated regions from its global network, with no critical dependencies on infrastructure outside the EU, operated and managed exclusively by resident and EU citizens, with an initial region in Brandenburg (Germany) backed by an investment of €7.8 billion until 2040.

On paper, the proposal addresses several concerns:

- Data Residency: everything is stored within Europe.

- Operational Control: only European personnel can access and manage the platform.

- Technical Autonomy: the region is isolated from other AWS regions.

Adding to this is the commercial argument: customers will continue to use the same APIs, services, and tools as in AWS’s global cloud, avoiding application rewrites or switching providers.

The Problem Isn’t in the Bits, but in the Laws

The friction point emerges when we stop looking at the physical map and instead analyze the legal framework. U.S. laws, especially the CLOUD Act and earlier statutes like the Patriot Act, give U.S. authorities the power to demand data from companies under U.S. jurisdiction, regardless of where the data is physically stored, as long as the company has “possession, custody, or control” over it.

In other words: if the parent company remains a U.S. corporation with ultimate control over infrastructure, software, or encryption keys, the promise of “sovereignty” clashes with an extraterritorial legal reality.

This is not an academic debate. Swiss data protection authorities, for example, have advised against the use of SaaS services from major U.S. providers (Microsoft 365, AWS, Google Cloud), precisely because of the risk of access under the CLOUD Act—even when data is stored in Europe and standard encryption measures are in place.

The contradiction is clear: GDPR and NIS2 build an architecture of European protection and control, yet the CLOUD Act creates a backdoor that, in certain cases, can compel data disclosure to a third country.

The Illusion of “Configuration-Based” Sovereignty

In response to these criticisms, hyperscalers have deployed a clear strategy: layering technical and corporate measures to insulate themselves… without changing the fundamental nature of the operator.

AWS talks about “sovereign-by-design”; Microsoft promotes Bleu alongside Orange and Capgemini in France; Google collaborates with Thales on S3NS. All these initiatives bolster local control (European subsidiaries, European personnel, data centers within the EU, advanced encryption, local key management), and some aim for certifications like SecNumCloud by the French ANSSI, which sets strict immunity criteria against extraterritorial laws.

These are steps in the right direction for certain uses. But even in these “trusted” models, the legal debate remains open:

Is it enough to rely on European majorities and local governance to fully neutralize legal obligations in the U.S.? Or is there an inherent structural tension that cannot be resolved as long as the core technology provider remains American?

The discussion is set against a backdrop where U.S. giants command between 70% and 80% of the global cloud market, and European efforts like GAIA-X have progressed much more slowly than anticipated.

What “Serious” Digital Sovereignty Means

From a European perspective, digital sovereignty is not just about deciding where data is stored. It encompasses at least three dimensions:

- Jurisdiction:

Data, systems, and operators are fully governed by European law, with no third-country laws imposing conflicting obligations. - Technological Control:

Having real capacity to audit, migrate, replicate, or replace infrastructure and software without being locked into a single provider (the so-called vendor lock-in). - Governance and Resilience:

Being able to decide, as a Union or Member State, what happens in cases of geopolitical crises, sanctions, trade conflicts, or regulatory shocks.

While “sovereign” clouds offered by U.S. companies improve the current situation—particularly in data residency and access controls—they do not fundamentally alter the fact that corporate control remains in Seattle, Redmond, or Mountain View.

The European Ecosystem That Already Exists… and Is Under-Viewed

While negotiations are ongoing with hyperscalers, Europe has a domestic infrastructure ecosystem that rarely makes headlines:

- Major European cloud providers like Stackscale, OVHcloud, Scaleway, Hetzner, Aruba Cloud, T-Systems, Deutsche Telekom, Orange Business, and other regional players;

- Hundreds of neutral data center operators and providers of housing and bare-metal services across Spain, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Nordic countries, and Italy;

- Public and private initiatives combining private cloud, edge computing, and managed services entirely under EU law.

These actors, with their strengths and weaknesses, have a significant advantage: they are not subject to the CLOUD Act or other extraterritorial U.S. laws and can align seamlessly with GDPR, NIS2, and future regulations on AI, industrial data, or cyber resilience.

The common argument against them is that “they don’t offer the full suite of services that hyperscalers do.” True: none currently offer the same breadth of products as AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud. But for a significant portion of workloads—especially critical infrastructure, sensitive data, or governance systems—the priority might not be having the latest managed service, but rather maximizing legal autonomy and control.

What Should Europe Do?

The discussion isn’t about demonizing U.S. providers. They have been and will continue to be key technology partners, often the most efficient option for many companies. But if the EU is serious about its digital sovereignty, it must go beyond simply accepting any “sovereign layer” they offer.

Some obvious strategies include:

- Condition public procurement: require that for certain data types and services, providers are not subject to extraterritorial laws incompatible with European law.

- Actively support European cloud and infrastructure providers: not just with rhetoric but through contracts, innovation programs, and stable regulatory frameworks.

- Encourage multi-cloud and open architectures: to avoid total dependence on a single actor and facilitate moving workloads across European and global clouds according to sensitivity levels.

- Legally clarify the limits of collaboration with “sovereign” clouds of U.S. origin: so administrations and regulated sectors know exactly what risks they are taking.

Sovereignty Is Not a Feature; It’s a Political Choice

The announcement of the AWS European Sovereign Cloud, like Microsoft and Google partnerships with European firms, shows that Brussels is already weighing in the agenda of cloud giants. This is good news: it indicates that regulatory and sovereignty concerns are no longer just background noise.

But it’s important not to confuse marketing slogans with reality. A data center in Germany, operated by European personnel and backed by major investment, can be a useful tool for many use cases. What it cannot be—while the company remains subject to U.S. law—is fully sovereign in European terms.

The ultimate choice is political, not technical:

either Europe decides that its most critical information and strategic infrastructure will always be under its own legal and technological umbrella, or it continues to rely on layers of sovereignty designed by third parties.

And one thing is clear: European alternatives do exist. The question is no longer whether they can match the giants, but whether they will be given the chance to demonstrate it.