Intel is back in the eye of the storm, but this time not because of the performance of its CPUs or a new delay in its roadmap, but due to something much more delicate: outright geopolitics applied to the semiconductor supply chain.

According to Reuters and expanded upon by various industry analyses, the company has been testing manufacturing tools from ACM Research —a supplier with a strong presence in China and a subsidiary included on U.S. sanctions lists— for its future Intel 14A node. There is no mass production, no chips sold, and no confirmed infringement… but the very fact that these tests are happening has set off alarms in Washington.

Testing is not production, but the context changes everything

In the semiconductor industry, “testing” a tool means introducing equipment into a controlled environment, validating its behavior, measuring parameters, and deciding whether it fits into a process still in development. It does not involve integrating it into a volume line or manufacturing chips for customers.

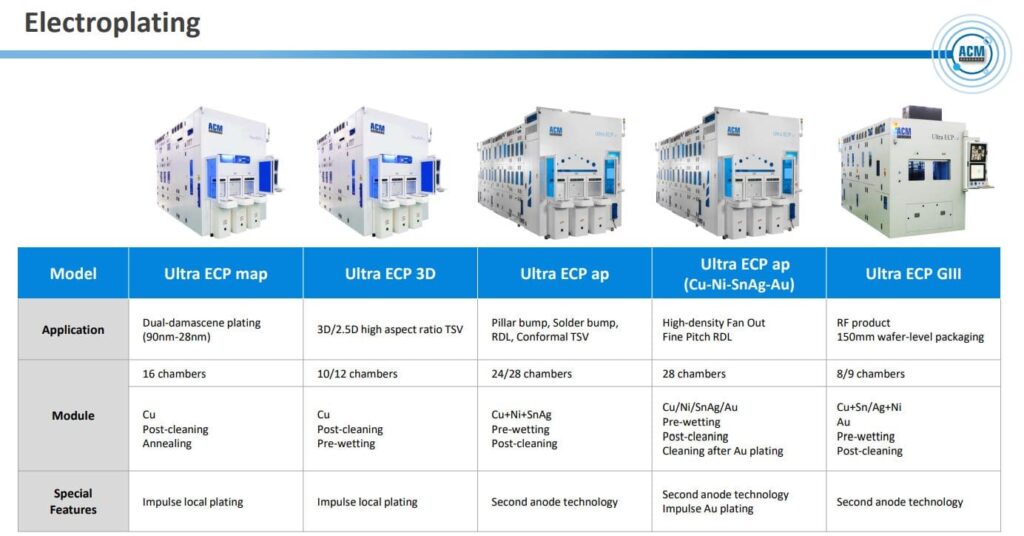

That is precisely what Intel engineers would have done with ACM Research’s wet etching equipment, thinking about future processes and referencing the Intel 14A node, which is not expected to go into production before 2027. Therefore, we are likely in an early stage of technological evaluation, a routine technical step.

The problem is that none of this happens in a vacuum. ACM Research is a U.S.-based company but whose core operations—R&D and manufacturing—are located in China. Its Chinese unit is subject to sanctions and is highly scrutinized for its integration into China’s semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem, including clients such as YMTC, SMIC, and CXMT—all under strong observation for their connections to the Chinese Communist Party and potential military applications.

In this context, the fact that Intel has allowed one of its most advanced centers to work with tools manufactured in China—potentially destined for its cutting-edge node—is a matter of much greater political significance than a simple laboratory test.

The major concern: Can information about the 14A node “leak”?

The primary worry in the White House is not just symbolic. Behind the controversy lies the fear of a possible transfer of knowledge to China on how one of the world’s most advanced lithography processes is being developed.

When a foundry like Intel evaluates a tool, it shares process data, operating conditions, cleaning and etching requirements, and generally a lot of sensitive information about how its node works. It doesn’t give the full design diagram directly, but it does involve a feedback loop with detailed technical information.

Meanwhile, ACM Research exemplifies the “national champion” Chinese supplier:

- It has grown significantly thanks to a strong base of domestic clients like YMTC and SMIC.

- It competes in critical segments such as wafer cleaning, etching, and electro-deposition against giants like Lam Research, Tokyo Electron, and Screen.

- It benefits from heavy subsidies and is clearly preferred as a local supplier for new Chinese factories.

Seeing such a company place evaluation-stage equipment in Intel, while the U.S. government allocates tens of billions of dollars in subsidies to Intel to reduce dependency on Asia, is a difficult political justification.

Intel caught between industrial pressure and political crossfire

From an industry perspective, Intel’s move makes sense: to catch up with TSMC and Samsung, it needs to evaluate everything available on the market. Developing a node like 14A involves comparing solutions from multiple manufacturers, pushing price and performance competition, and avoiding premature exclusivity with any single provider.

However, politically, maneuvering room is becoming narrower. The U.S. has made semiconductor supply chain control a strategic priority. It’s no longer just about where chips are manufactured or which nodes are exported to China; it also includes:

- Who supplies the process tools.

- At what stage of development they are used (testing, pilot production, volume manufacturing).

- Whether there’s any risk of transferring know-how to sensitive actors.

In this ecosystem, the fact that Intel—recipient of the CHIPS Act and champion of “rebuilding” advanced manufacturing in the U.S.—is testing equipment from a Chinese integrated supplier fuels unavoidable tensions.

Violation of sanctions or coordination failure?

Currently, there is no public evidence that Intel has violated existing sanctions or that a transfer of technology outside legal parameters has occurred. Everything points to a limited qualification phase, without use in production lines or mass sales of equipment.

But the uncertainties remain:

- Was the administration informed about these tests?

If so, the scandal shifts to the transparency of the process and how public communication was managed. - Were safeguards respected to prevent cross-access to sensitive information?

ACM Research claims its U.S. operations are separate and protected. However, the current political climate is deeply skeptical of such assurances. - Can Intel justify to the public and regulators the use of Chinese tools while requesting subsidies to “decouple” from China?

The debate is not only technical but also reputational: the “Made in America” narrative becomes complicated if some critical equipment originates from the country the U.S. wants to avoid relying on.

All this comes at a time when the U.S. government is tightening export controls, pressuring allies to limit sales of equipment to China, and trying to solidify advantages in advanced nodes.

A symptom of the new war over the supply chain

The Intel–ACM case, at its core, reflects a broader phenomenon: the silent war for control over every link in the semiconductor supply chain.

For decades, the industry operated with a high degree of pragmatic globalization: ASML in the Netherlands with EUV, Japan dominating lithography and cleaning, the U.S. in chip design and key equipment, Taiwan and Korea as advanced manufacturing hubs, and China as an assembler and aspiring node developer.

Today, every order, test, and supply agreement is viewed through a geopolitical lens:

- China seeks to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers and bolster its domestic champions like ACM Research.

- U.S. aims to slow Chinese technological progress while rebuilding its own industrial capacity.

- Europe and Japan try to avoid being caught in the middle and focus on strengthening their own supply chains.

Intel, aiming to be a global industrial player and a symbol of the “return” of manufacturing to the West, stands directly in the crossfire.

What’s next?

The incident is under review, and all signs point to political pressure to clarify the extent of these tests and their conditions. Possible outcomes range from a discreet reprimand and internal procedural adjustments at Intel to new formal restrictions on the types of equipment public-investment recipients can evaluate.

Regardless of the outcome, this episode sends a clear message: in the era of the chip war, there are no “innocent tests.” Every tool introduced into a state-of-the-art cleanroom is also a move on the geopolitical chessboard.

Sources: elchapuzasinformatico, Reuters, and semianalysis