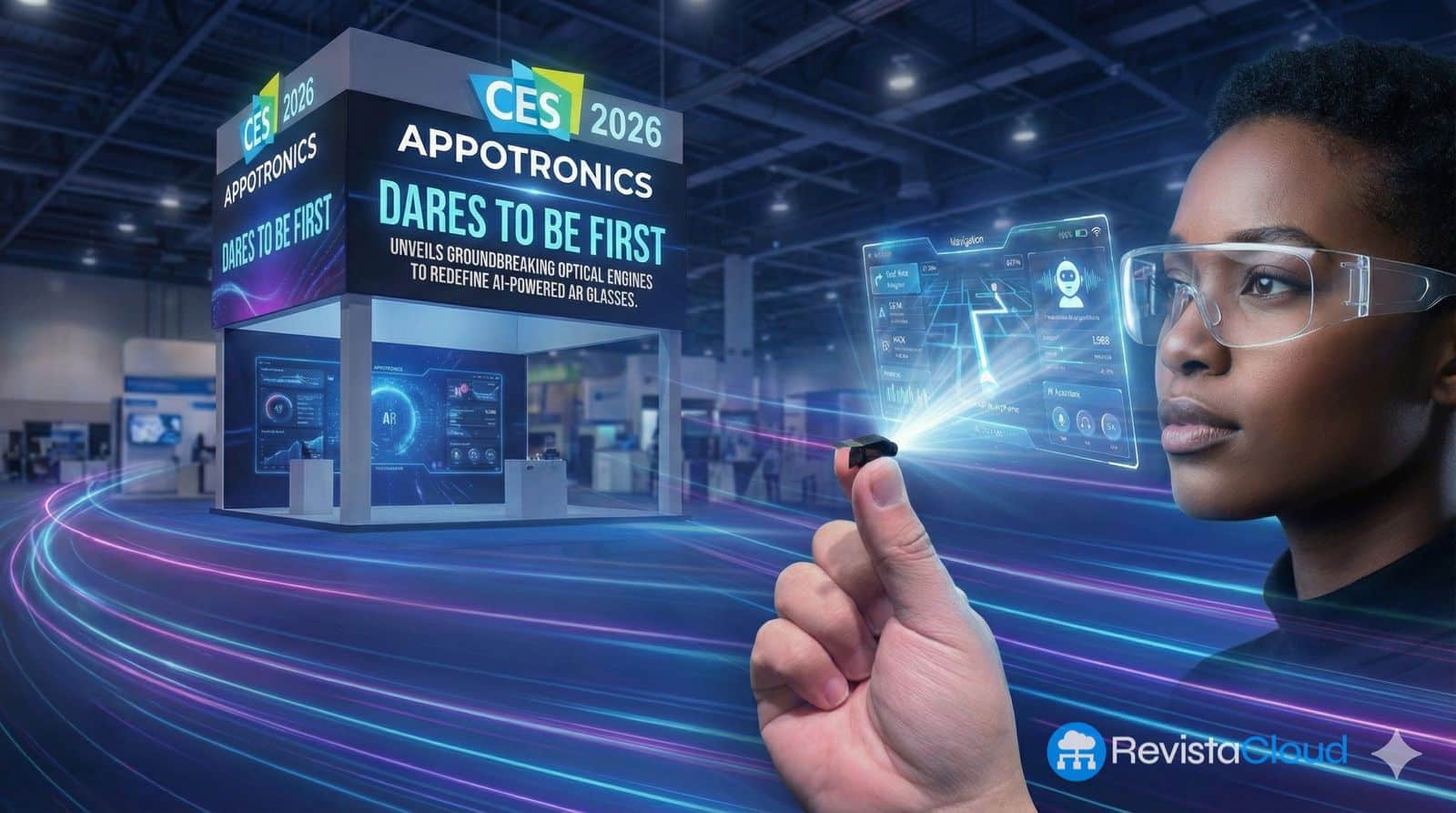

For years, augmented reality (AR) glasses have been caught in an awkward triangle: to be useful, they need brightness, sharpness, and increasingly “smart” features; to be desirable, they must resemble normal glasses; and to reach the mass market, they must be manufactured with reasonable costs, power consumption, and failure rates. At CES 2026, Appotronics has decided to tackle the problem where it hurts most: the “optical engine,” the module that, in practice, determines the size, weight, and part of the power consumption of AR glasses.

The company — known for its ALPD laser technology and for its agility in both consumer and professional optics — has announced two new optical engines under the Dragonfly family: Dragonfly G1 Mini and Dragonfly C1. The message is not just “smaller,” but a design approach: moving from a traditional dual-motor system (one per eye) to a binocular system with a single motor. This apparent simplification could become a huge leverage for AR glasses to jump from niche to a genuinely “everyday” format.

The key idea: a single motor for binocular vision

The classic architecture of binocular AR glasses usually involves two optical motors (left and right), which multiplies volume, weight, mechanical complexity, and assembly/calibration costs. Appotronics proposes an alternative: a “singular-engine binocular design” that aims to provide binocular vision from a single module, reducing parts, failure points, and industrial design constraints.

In other words: less “duplicated hardware” and more room for manufacturers to allocate space to batteries, electronics, cooling, cameras, or even frame design.

Dragonfly G1 Mini: size as a selling point

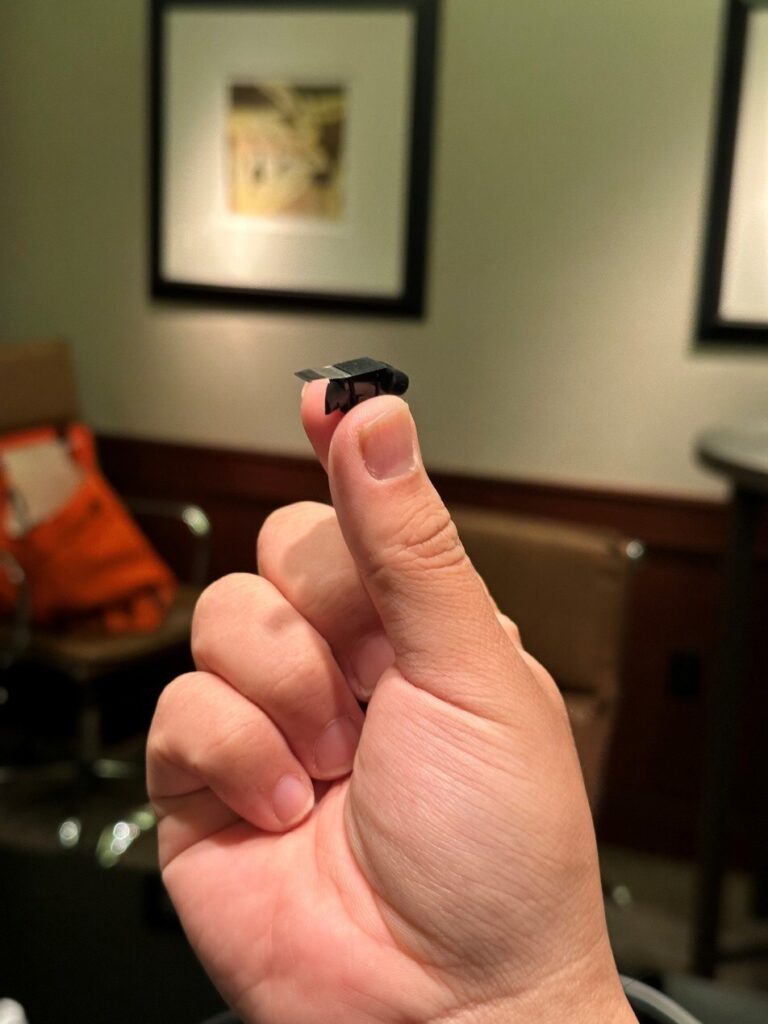

The Dragonfly G1 Mini is presented as a milestone in miniaturization: 0.2 cc volume, smaller than the previous Dragonfly G1 (0.35 cc), with a contrast ratio of 1,000:1 according to the company’s data. In the race for form factor, shaving off tenths of a cubic centimeter is not a trivial detail: it allows the optics to stop dominating everything else.

Appotronics frames this advancement within a very specific narrative: lighter glasses, closer to the aesthetic of a product that doesn’t “shout” technology… and that can stay comfortably on the face for hours without fatigue.

Dragonfly C1: the leap to “full color” binoculars from a single module

If the G1 Mini is size-focused, the Dragonfly C1 embodies ambition: Appotronics presents it as the first full-color binocular engine based on a dual-split RGB LCoS scheme, also within the “single motor” concept. Its declared volume is 0.4 cc.

For the industry, the promise is twofold:

- Full color in a binocular system without duplicating motors.

- Reduced volume, weight, and complexity, with a direct impact on manufacturing and power consumption.

In a market where many AR prototypes end up resembling “reduced helmets” or bulky glasses, any advancement that brings the format closer to traditional frames is golden.

The psychological goal: under 30 grams

Appotronics articulates a target that actually summarizes the entire industry’s dream: for AR glasses to feel like regular glasses. In their demos, the company mentions An ideal goal below 30 g for a “all-day” product.

And here’s an example aimed at demonstrating feasibility: according to the release, the Sharge Loomos AI Display Glasses S1, equipped with Dragonfly G1 Mini, achieve a total weight of 29 g. Comparing weights in smart glasses isn’t always straightforward because it depends on hardware components (cameras, batteries, displays, audio, etc.) and device function, but Appotronics’s point is clear: if the optics get lighter, the rest of the design has room to become “wearable”.

As a benchmark, current market references like the Ray-Ban Meta (smart glasses focused on camera/audio, not AR with binocular display) usually hover around 48.6–50.8 g depending on specifications. This illustrates how challenging it is to go below certain thresholds even without full AR systems.

Why does the optical engine matter so much?

In AR, the “engine” isn’t a minor detail: it’s the physical heart of the product. It determines:

- Volume and weight distribution (comfort, stability on nose/ears).

- Energy efficiency (actual battery life).

- Assembly complexity (cost, yield, calibration).

- Design freedom (thinner frames and more “normal” aesthetics).

This is why an architectural change that avoids module duplication can have a domino effect: fewer parts, less critical tolerances, lower power consumption, less heat… and more room for software, batteries, and sensors that make glasses useful.

Quick table: what Appotronics announced

| Optical engine | Focus | Declared volume | Highlighted data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dragonfly G1 Mini | Binocular with single motor (“singular-engine” concept) | 0.2 cc | Contrast 1,000:1 |

| Dragonfly C1 | Full-color binocular from a single module | 0.4 cc | RGB dual-split LCoS |

Beyond AR: laser for entertainment and “wellness”

Appotronics leverages CES to remind that their business isn’t limited to AR. The group also showcases applications of their laser technology in personal care devices (such as solutions for hair and skin) and, through their subsidiary Formovie, advances related to their ALPD technology in home entertainment (projection).

This helps reinforce their credentials: they’re not presenting as a startup with a prototype, but as an established player with industrial experience aiming to translate that expertise into the “great promise” of consumer AR.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does it mean for an optical engine to be “binocular with a single motor”?

Instead of using two separate modules (one per eye), the system tries to generate the image for both eyes from a single module, reducing volume, weight, and complexity.

Why is weight (e.g., 30 g) so critical in AR glasses?

Because prolonged wear depends on comfort. When weight increases, it puts pressure on the nose and ears and worsens stability; this limits the device’s suitability for “all-day” use.

What does full color in AR bring compared to more limited solutions?

It enables richer interfaces, more legible content, and experiences closer to real screens. Practically, it opens the door to more “mainstream” uses—navigation, contextual information, productivity.

When might truly affordable and wearable AR glasses arrive?

The main barriers are often optics, cost, and power consumption. If modules like these reduce complexity and improve scalability, the leap will depend on manufacturers integrating the entire ecosystem (batteries, software, AI, sensors) without skyrocketing the price.