The idea that the next decade will be driven by Artificial Intelligence is often framed around software, models, and digital services. But an analysis circulating online, which attributes a central thesis to BlackRock, points in the opposite direction: the real engine isn’t a single technology but a wave of multitrillion-dollar investment in infrastructure that, purely through its physical weight, rewrites the economic cycle.

In this perspective, three forces are pushing simultaneously:

Two parallel efforts: repairing the 20th century and building the 21st

The thesis starts from an uncomfortable reality for advanced economies. On one side, developed countries are burdened with aging physical infrastructure: electrical grids, bridges, water and transportation systems that in many cases were designed mid-20th century and are now nearing the end of their useful life. Modernization is not optional: it’s preventive maintenance on a national scale.

On the other side, the digital economy doesn’t just “consume” infrastructure: it demands it from scratch. Data centers, additional electrical capacity, communication networks, energy logistics, and systems designed to support increasingly intensive computing activity. In this narrative, the 21st century resembles less a software update and more an expansion of physical infrastructure.

This is where friction arises: when both needs coincide, the world not only competes for talent and capital but also for permits, transformers, substations, cabling, materials, and skilled labor. In other words: for what cannot be scaled with a click.

Urbanization: when cities stop absorbing without breaking

The cited analysis introduces a figure meant to shift the “mental scale” of the debate: by 2050, almost 7 billion people will live in cities. This isn’t just a demographic statistic; it’s a direct pressure on already saturated urban systems.

More urban population means increased demand for housing, transportation, water, and energy. And also more reliance on resilient networks: if growth is concentrated in metropolitan areas, any failure becomes systemic. Therefore, urbanization is viewed not merely as a social trend but as a multiplier of investment in basic infrastructure.

Global trade: from discourse to nearshoring movement

The second force is the reorganization of global trade. According to the argument, nearshoring transitions from a conceptual idea to concrete action: major manufacturers plan to produce closer to their end markets. This requires new factories, logistics, energy, and raw materials, along with less fragile supply chains.

An important nuance is that “closer” manufacturing doesn’t automatically reduce costs: it demands upfront investment. And this investment tends to be physical and slow. Unlike other cycles where expansion is measured in licenses and services, here it’s measured in industrial land, electrical connections, and installed capacity.

AI as a catalyst: it’s not just about GPUs, but networks

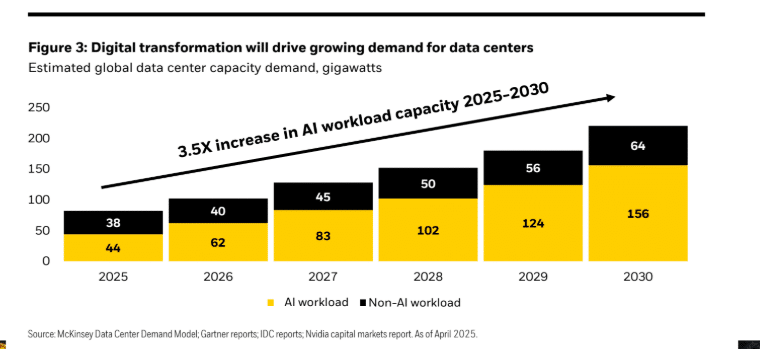

The third and most publicly discussed vector is Artificial Intelligence. The text attributed to BlackRock suggests that data center capacity could multiply by 3.5 times between 2025 and 2030, and that this growth would collide with an electrical grid unprepared for such a leap.

This is the conceptual shift echoed in the thesis: AI isn’t an “asset-light” phenomenon. It doesn’t just require investment; it demands real infrastructure and long timelines. Bottlenecks are not only about innovation but also about physical constraints: permits, energy, networks, equipment, and skilled personnel. When physical limits are in play, the value tends to concentrate among those who can build, operate, and connect.

Within this context, the debate moves from “who has the best model” to “who has access to power, land, interconnection, and execution capacity.” In this view, AI resembles more a heavy industry of the new generation than a purely digital wave.

“The next big cycle isn’t won with endless multiples”

The conclusion, almost provocatively framed, is that the next cycle won’t be driven by “cheap software” or frictionless growth narratives. It will be won by concrete, copper, electricity, and installed capacity.

The message doesn’t deny the importance of technology; it grounds it. It suggests that the future’s economic power could shift—or at least be redistributed—toward those who control the physical assets that enable large-scale computing: energy infrastructure, networks, data centers, and everything that turns a digital promise into a tangible service.

With this perspective, the key question isn’t whether there will be investment in infrastructure but who will reach the bottlenecks first and who will have the capacity to overcome them. Because if infrastructure sets the pace, then speed ceases to be a software advantage and becomes an execution advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does it mean that AI isn’t an “asset-light” phenomenon?

It means that deploying AI depends on physical assets: data centers, electrical capacity, networks, cooling, and permits. Talent and software are not enough; installed capacity is required.

Why does the electrical grid become a bottleneck for data centers?

Because growing demand can outpace available capacity and expansion timelines. Connecting additional power isn’t immediate: it requires construction, equipment, and authorization processes.

How does nearshoring impact infrastructure investment?

Relocating production closer to end markets entails building new factories, logistics networks, and energy supply systems. It’s a reorganization that demands CAPEX and long-term planning.

Which sectors tend to benefit most during an infrastructure “supercycle”?

Generally, those linked to installed capacity and physical infrastructure: energy, networks, critical materials, specialized construction, and digital infrastructure operators like data centers and connectivity providers.

via: Hector Chamizo