Tesla aims to turn Optimus into the company’s major strategic shift: a humanoid robot capable of working in factories, performing repetitive tasks, and eventually entering homes and professional environments. Elon Musk has emphasized relocating production and final assembly to the United States, in line with the idea of “reindustrializing” advanced manufacturing. However, the reality of modern robotics is less patriotic and much more practical: the supply of components, sub-assemblies, and critical materials remains concentrated in China.

This is what’s already being described by some analysts as an “Optimus chain”: a supply network that, even if the robot is assembled on U.S. soil, depends on a mature Asian ecosystem for the parts that make a humanoid more than just a prototype.

From Automotive to Humanoids

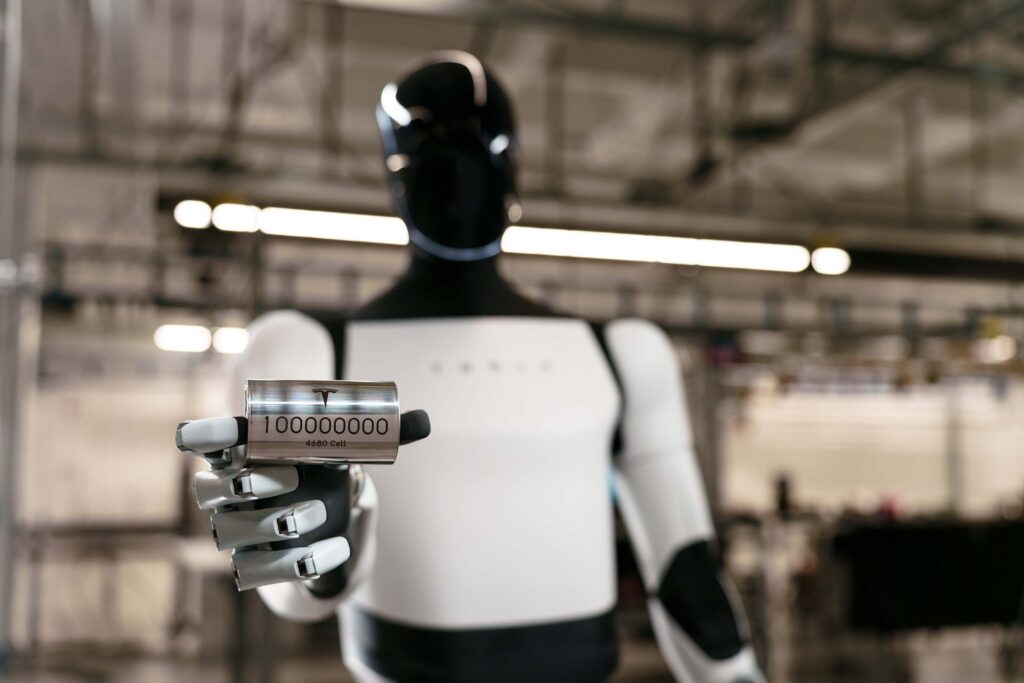

Tesla isn’t treating Optimus as a marginal experiment. In its corporate documentation and recent statements, the company has reiterated its roadmap: launching the third generation of the robot (Gen 3) in the first quarter of 2026, preparing the first production line, and starting manufacturing before the end of 2026, with the ambitious goal of scaling up to a planned capacity of 1 million robots per year. Tesla also indicates that the Optimus project in California is “under construction,” a nuance suggesting industrial deployment rather than just a lab project.

The message is reinforced by internal movements: Musk has suggested that Tesla could end Model S and Model X production in Q2 2026 to free up space at the Fremont plant and prioritize Optimus. The signal is clear: the robot is no longer a futuristic concept but a competitor for factory space, investment, and resources.

China, the Invisible Advantage: Parts, Expertise, and Scale

In humanoid robotics, “having an idea” isn’t enough. It must be turned into reliable actuators, compact gearboxes, precise motors, sensors, wiring, batteries, boards, connectors, and hundreds of components that must fit with millimeter tolerances. And that’s where China has the advantage.

According to industry sources cited by specialized media, Tesla has been working with hundreds of Chinese suppliers for about three years now, not just purchasing parts but collaborating with some on research, development, and hardware design. The picture emerging is of a deep relationship: suppliers who don’t just serve as catalog providers but participate in defining the product itself.

The core argument is summarized by recent analysis: although the final assembly might take place in the U.S., the “chain” of robotics will continue to depend on China for manufacturing volume, speed, and specialization in key components. This isn’t an incidental dependency: most critical materials and supplies are concentrated there, posing a direct risk if trade restrictions or licensing issues arise.

The Cost of “Disconnecting” from China: Nearly Tripling Robot Price

A key fact illustrates why this dependence can’t be fixed with a simple “let’s bring it home.” Morgan Stanley estimated that developing a supply chain for Optimus Gen 2 without Chinese involvement would nearly triple manufacturing costs.

The most notable example is actuators—the mechanical heart that moves the joints. Without China, their cost would jump from about $22,000 to $58,000. The chip and software module would also increase (from around $3,000 to $7,000). Overall, the total bill of materials would soar from roughly $46,000 to $131,000, with similar increases in hands, feet, artificial vision systems, and batteries.

In other words: building a competitive humanoid isn’t just an engineering challenge; it’s a race to dominate the value chain and unit costs. If Tesla wants Optimus to reach a viable price point for businesses (and later consumers), cutting off the Chinese supply chain abruptly wouldn’t be a technical step but an economic verdict.

The Rare Earths Bottleneck: When a Single Part Holds Up the Schedule

The dependency isn’t limited to screws or casings. An especially delicate point is the magnets and materials tied to rare earth elements, essential for motors and actuators.

By April 2025, Musk already acknowledged that Optimus production was impacted by Chinese restrictions on rare earth magnet exports. As he explained, China was demanding guarantees that these materials wouldn’t be used for military purposes, and Tesla was working to obtain export licenses—a process that could take weeks or months. It’s a textbook example: even with a custom design and industrial ambition, a single regulated component can halt scaling efforts.

This fragility turns the “Optimus chain” into a geopolitical chessboard. If permits are tightened or flows slow down, the impact isn’t in headlines but in stopped production lines, delays, and additional costs.

An Industrial Tug-of-War with a Domino Effect

Tesla’s strategy comes at a time when China isn’t just manufacturing components—they are building their own leadership in humanoid robotics. Morgan Stanley pointed out that China has issued five times more humanoid-related patents than the U.S. over the past five years, indicating not just industrial muscle but also innovation strength.

For Tesla, the challenge resembles the early days of consumer electronics: the brand can design, integrate, and define the final product, but the global supply chain determines what’s possible to produce, at what cost, and at what pace.

The big question isn’t whether Optimus will walk better or have a more sophisticated hand. It’s whether Tesla can industrialize it without getting caught between two opposing forces: the desire to produce in the U.S. and a supply chain that, for now, still primarily speaks Mandarin.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is the “Optimus chain” and why does it matter?

It’s the network of suppliers, materials, and subcomponents needed to build the Optimus robot. It matters because, even if final assembly happens in the U.S., many critical parts still depend on Chinese manufacturers and supplies.

Which components make building a humanoid outside China most difficult?

Actuators (the mechanisms moving the joints) are the biggest cost and complexity factor. Vision systems, batteries, “dextrous” hands, and integrated electronic components also weigh heavily, along with regulated materials like rare earth magnets.

When does Tesla plan to start mass-producing Optimus?

Tesla has announced that it will unveil Optimus Gen 3 in the first quarter of 2026 and intends to begin production before the end of that year, with a long-term planned capacity of 1 million robots annually.

Why are rare earth elements a risk to Optimus’ schedule?

Because some magnets and materials used in motors and actuators are subject to export controls. Tesla has already recognized that Chinese restrictions impacted production, requiring additional licensing and validation processes.

via: scmp