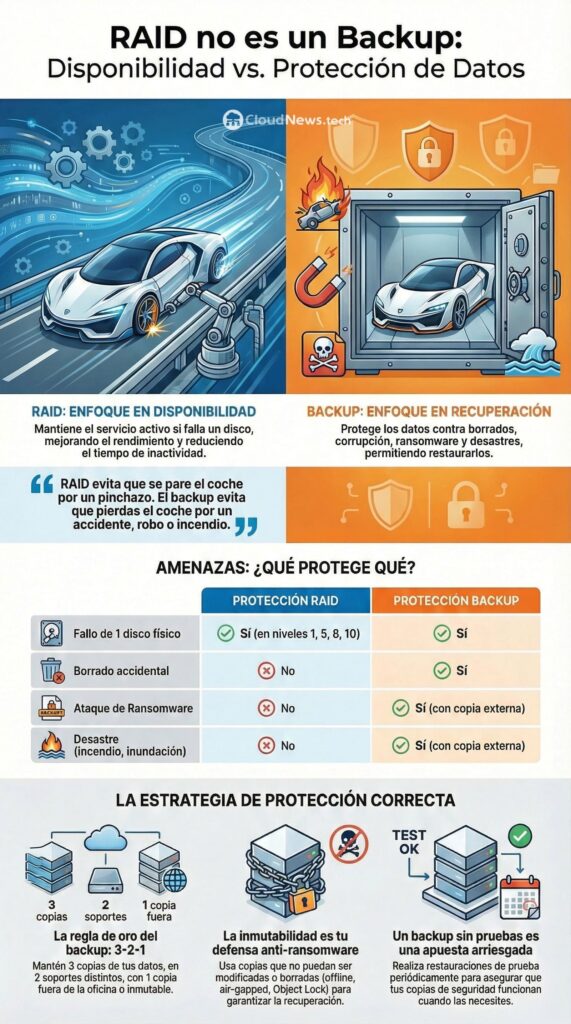

In many companies, storage is designed with a clear goal: to keep the service running when a disk fails. That’s where RAID plays its role effectively. The problem arises when it is assigned another purpose: to protect data against any incident. And that, simply put, is not true.

A well-planned RAID improves availability and, in some cases, operational continuity in the face of physical disk failures. But it does not prevent accidental deletions, logical corruption, human errors, ransomware encryption, site loss, compromised credentials, or controller failures. In other words: RAID reduces the impact of one type of failure; backups cover many more.

What RAID genuinely contributes to a company

RAID is a technique of redundancy and/or distribution that combines multiple disks into a logical volume. Its main contributions are:

- Disk failure tolerance (depending on RAID level).

- Performance improvement (especially read performance and some write patterns).

- Reduced downtime during a specific physical failure.

What it does not provide:

- Version history (there’s no “undo” if a file is deleted).

- Protection against malware/ransomware (if the volume is encrypted, RAID is encrypted too).

- Protection from silent corruption or application errors.

- Disaster recovery (fire, flood, theft, severe power outages, mass errors).

Most common RAID levels and when they make sense

RAID 0 (striping, no redundancy)

Pure performance. A failure results in total data loss. Only useful in temporary caches, render scratch disks, labs, or non-critical data.

RAID 1 (mirroring)

Duplicates data on two disks. Typically used for system volumes, controllers, small services, or boot drives where simple recovery is prioritized. It does not protect against deletions, ransomware, or corruption.

RAID 5 (distributed parity, minimum 3 disks)

Balances capacity and tolerance for a single disk failure. Widely used in NAS and file environments, but with an important caveat: with large disks, reconstruction can be lengthy, increasing risk during rebuilds. Heavy write workloads can also impact performance.

RAID 6 (double parity, minimum 4 disks)

Tolerates the failure of two disks. Common in environments with large volumes, repositories, and arrays where more margin is desired during rebuilds. Writes are more penalized compared to RAID 5, but resilience is higher.

RAID 10 (1+0: mirror + striping)

Often the “classic” choice for databases, virtualization, and high IOPS workloads: good performance and strong redundancy. Comes at the cost of capacity (approximately 50% usable) and requires more disks.

The often-overlooked layer: reconstruction and “window of risk”

When a disk fails, RAID enters degraded mode. From that point, the system faces a window of risk:

- The rebuild can take hours or days depending on size, workload, and disk type.

- Performance may decline just when stability is most needed.

- A second failure (or unrecoverable sector) can bring down a RAID 5 volume.

Therefore, in 2026, the real debate is not “which RAID is better” but which RAID makes sense based on disk size, criticality, and RTO/RPO for the service.

Controller, cache, and policies: where the battles are won (or lost)

In enterprise environments, RAID often resides in one of these configurations:

- Dedicated RAID controller (PERC, Smart Array, MegaRAID): provides cache, BBU/flash-backed cache, and safer write policies.

- HBA + software (mdadm, ZFS): offers transparency and control; with good design, it can be excellent but requires operational discipline.

- Array/NAS/SAN: RAID is part of the storage system and exposed via iSCSI/NFS/FC, often alongside snapshot, replication, and other layers.

Here’s a useful rule: if the controller (or its cache) fails, the RAID can turn into your incident. That’s why stable firmware, spare parts, compatibility, and replacement plans are so critical.

The phrase worth tattooing: RAID does not replace a backup policy

The right strategy typically combines several elements:

- RAID for availability (keeping services online during disk failures)

- Snapshots (quick, effective against recent errors, but not foolproof if an attacker gains control)

- Backups with retention and testing (the only true guarantee of recovery)

- Immutability / air-gapping / offsite to resist ransomware and massive errors

- Disaster recovery (DR) if business continuity cannot rely solely on a single data center

Simply put: RAID prevents the “car from stopping due to a flat tire”. Backup prevents “losing the car” due to accidents, theft, or fire.

Minimum best practices

- Apply the 3-2-1 rule: 3 copies, 2 different media, 1 offsite or immutable copy.

- Keep at least one copy offline or immutable (Object Lock, WORM, hardened repositories).

- Test restores regularly (a backup is worthless if you can’t restore it).

- Separate credentials and limit privileges (an admin can delete, so can an attacker with those credentials).

- Monitor disk health, SMART data, latencies, and read errors to catch issues early.