Emails are used daily for work, registering for services, recovering passwords, or receiving invoices. However, few people stop to think about what happens “behind the scenes” when a message leaves the mobile device and arrives seconds later in another inbox. It’s not magic: these are open protocols that have been quietly doing their job for decades with reliability and discretion.

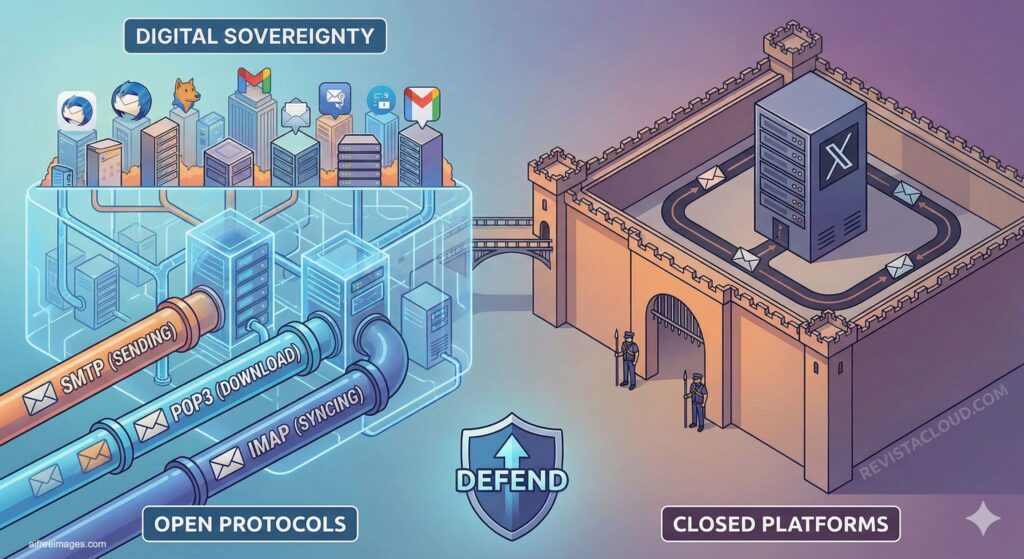

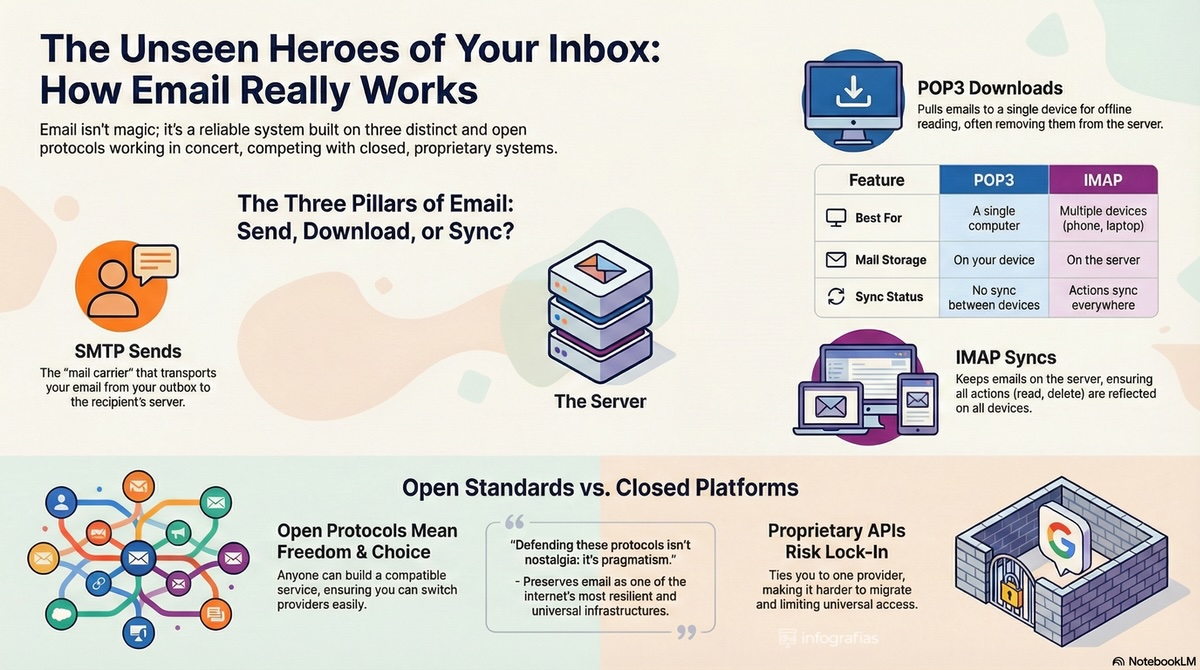

The concept is simple and revealing at the same time: SMTP sends, POP3 downloads, and IMAP syncs. Three separate components with distinct functions that explain why email has survived technological fads, platform wars, and device changes. Because of this, the current debate isn’t just technical; it’s also strategic. In a world where big players push toward APIs and proprietary flows, understanding these standards is a way to defend interoperability and prevent vendor lock-in.

SMTP: the “mailman” activated when clicking Send

When a user writes an email and clicks “Send,” SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) comes into action. Its mission is clear: transport the message from the email client to the server, and from server to server, until the recipient receives it.

In practice, SMTP is the gear that maintains the “federated” nature of email: it doesn’t matter if the sender uses a custom domain, a small provider, or a major platform; as long as everyone speaks SMTP, email flows seamlessly.

Typically, SMTP is associated with these ports:

- 25: the historic port for server-to-server transit (becoming more filtered by providers to prevent abuse).

- 587: the recommended port for authenticated client sending (most common in modern setups).

- 465: sending with implicit encryption (used in certain environments and providers).

The key nuance is that SMTP is not designed to “receive” mail nor to store mailboxes: its role is outgoing. That’s why talking about “email protocols” involves a system of interconnected parts working together.

POP3: downloading email to have it “locally”

The second main player is POP3 (Post Office Protocol). POP3 was created with a clear philosophy: download messages to the device so users can read them offline. Typically, POP3 can delete messages from the server after download (though many clients allow keeping copies).

In practical terms, POP3 is suitable when:

- Only one computer is used as the working hub.

- Simple, “local” management is desired.

- Reading without constantly relying on the server is a priority.

Common ports include:

- 110: POP3 without encryption (now rarely recommended on open internet).

- 995: POP3 with encryption (POP3S).

The main limitation of POP3 in 2026 is the same as ever: it doesn’t sync changes between devices. If you mark an email as read, move it to a folder, or delete it on one device, those changes aren’t automatically reflected elsewhere. With mobile, laptop, and tablet all in use, this approach falls short for many users.

IMAP: email as a synchronized mailbox across multiple devices

This is where IMAP (Internet Message Access Protocol) comes in, aligning better with today’s reality. IMAP keeps messages on the server and syncs actions (read, deleted, folders, tags) across all devices. In other words: the user manages a single, central mailbox rather than scattered copies.

IMAP is preferred when:

- Accessing email from multiple devices.

- Consistency is required: what’s done on the mobile appears on the PC.

- Working with folders and complex organization.

Typical ports:

- 143: IMAP without encryption (not recommended today on the open internet).

- 993: IMAP with encryption (IMAPS).

The traditional disadvantage of IMAP is that it requires a connection and consumes server space, though most clients allow local caching for smoother operation. In exchange, it provides what has become a basic requirement: true synchronization.

The elephant in the room: open standards versus closed APIs

Beyond choosing POP3 or IMAP, the core issue is that email is one of the last major open standards on the internet that continues to operate globally. And that matters.

Open protocols have advantages that are hard to replace:

- True interoperability: any compatible provider can communicate with another without prior permission.

- Portability: switching providers or hosting email on your own server is feasible.

- Competition and diversity: it prevents communication from being confined to just two or three platforms.

- Auditability and transparency: as public standards, they can be reviewed and improved over time.

Conversely, when access shifts toward proprietary APIs, the risks are well-known: dependency on a single provider, changing terms, regional restrictions, integration costs, limited functionalities, and most importantly, loss of the universal nature of email. This isn’t just theory: in many organizations, using standard protocols versus “marrying” a platform determines their ability to migrate, negotiate, or maintain technological sovereignty.

A simple (and practical) conclusion

The map hasn’t changed: email continues to work thanks to a clear division of tasks.

- SMTP sends.

- POP3 downloads.

- IMAP syncs.

And because it’s simple, standard, and open, email remains one of the most resilient infrastructures on the internet. Defending its protocols isn’t nostalgia: it’s pragmatism.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s better for using email on mobile and computer: POP3 or IMAP?

IMAP is usually the better choice if you check email from multiple devices, because it keeps the mailbox synchronized and consistent across all of them.

Why is port 587 considered the recommended port for SMTP?

Because it’s designed for sending from modern clients with authentication configured. Port 25 is mainly reserved for server-to-server transit and is often filtered by providers to reduce abuse.

Can POP3 be used securely today?

Yes, but it’s recommended to use it with encryption (typically on port 995) and strong credentials. However, its model is less ideal if you use multiple devices.

What do you lose when a provider promotes the use of proprietary APIs instead of standard protocols?

You lose universal interoperability and increase dependency risks: harder migrations, integrations limited by provider policies, and less ability to choose alternatives.