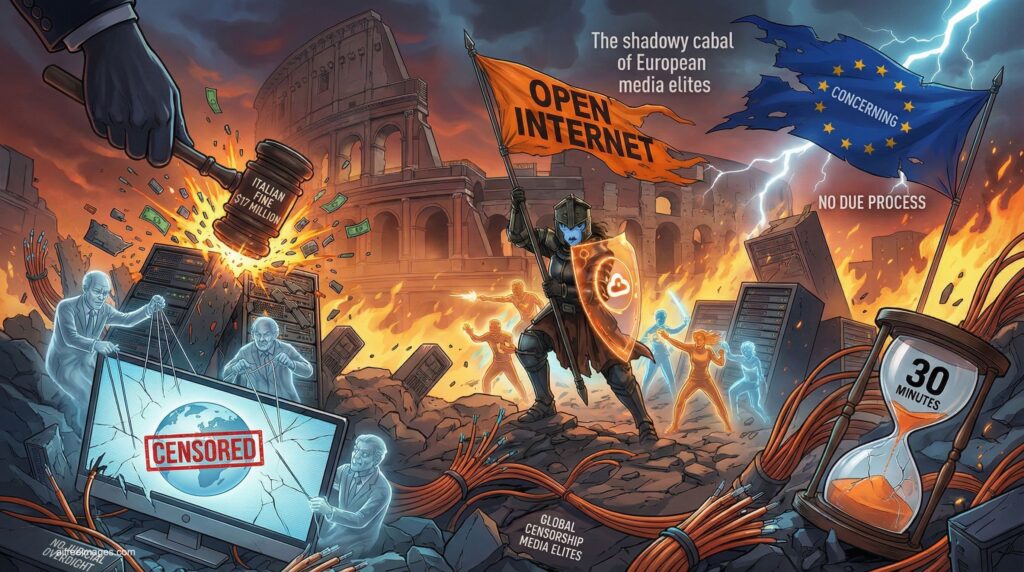

The dispute between European regulators and private Internet infrastructure just heated up. Matthew Prince, CEO of Cloudflare, has responded sharply on X after Italy imposed a fine on the company for its role in blocking pirate content. The episode is not just a corporate spat: it raises an uncomfortable question for the European digital ecosystem once again: How far can a state go when demanding a global provider to “turn off” parts of the Internet, and with what guarantees?

What happened: a multi-million dollar fine and an accelerated blocking order

The Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni (AGCOM) announced a penalty exceeding 14,000,000 € against Cloudflare for failing to comply with a prior order related to Italian anti-piracy regulations and its platform Piracy Shield. According to the regulator, Cloudflare was required to implement measures to disable access to domains and IP addresses flagged by rights holders, including DNS resolution disabling and traffic routing toward certain IPs, or equivalent measures that prevent end-user consumption of illegally distributed content.

In the official statement, AGCOM frames the case as a significant precedent due to Cloudflare’s influence in the web services landscape and because, it argues, a broad proportion of the sites subject to blocking use the company’s services. The authority adds a detail illustrating the system’s operational scale: since its launch, more than 65,000 FQDNs and around 14,000 IPs have been disabled via Piracy Shield.

Prince’s response: “censorship,” “lack of due process,” and threat of withdrawal

Cloudflare’s CEO has turned the fine into a political and reputational showdown. In his message, Prince characterizes the scheme as a “strategy to censor the Internet” and criticizes the demand for rapid action — mentioning a 30-minute deadline — and lack of guarantees: “without judicial oversight, without due process, without appeal, and without transparency,” he states.

The most sensitive point for the technical community is the scope Prince attributes to the order: it would not only target “removing” clients or services but also affect 1.1.1.1, Cloudflare’s public DNS resolver. This raises the classic fear of overblocking: acting at the DNS or IP level in shared infrastructures risks not only blocking “bad” content but also impacting legitimate sites and services.

Prince also denounces an extraterritorial dimension: he claims Italy wants the blocking to be effective globally, not just within Italian borders. In his narrative, this leap turns an anti-piracy mechanism into a tool that could be used by a country to impose what is acceptable elsewhere.

“Play stupid games…”: the economic and operational gambit

Apart from the tone, what’s crucial is the list of measures he says he is “considering”:

- Disrupt cybersecurity services pro bono associated with the Milano-Cortina Games.

- Withdraw free cybersecurity services for users based in Italy.

- Remove servers in Italian cities.

- Cancel office plans and investments in the country.

Meanwhile, he states he will travel to Washington to discuss the matter with US officials and will talk with the IOC to “explain the risks” if Cloudflare withdraws.

It’s important to highlight a nuance: part of Prince’s message mixes facts (the fine, legal conflict) with judgments (“censorship,” “conspiracy,” etc.) and hypothetical threats (“we are considering…”). In other words: the CEO aims to raise the political stakes of the conflict and leverage the country’s dependency — infrastructure, performance, DDoS protection, latency — as a bargaining chip.

What’s truly at stake: shared infrastructure vs. swift orders

For a tech publication, this case exemplifies the classic clash between governance and Internet architecture:

- DNS as control point: blocking via DNS is effective and swift but also “clumsy” if not accompanied by clear rules, auditing, and correction mechanisms.

- Shared IPs and CDNs: in services like fronting, reverse proxy, and CDN, multiple domains can coexist on networks that do not map straightforwardly to a single IP. Blocking by IP increases collateral damage risk.

- Reaction time: minutes may be reasonable to stop live illicit retransmissions but raise error risks if verification and transparent rollback aren’t integrated.

- Territorial scope: demanding “global” compliance from a transnational provider opens debates about digital sovereignty, trade, and jurisdictional conflicts.

Meanwhile, AGCOM defends its approach by arguing that regulations extend beyond hosting to “information society services” that facilitate accessibility (explicitly mentioning public DNS, VPNs, and search engines), wherever they are based. This approach conflicts with Cloudflare’s vision, as the company considers itself a neutral infrastructure provider that should not carry out orders lacking adequate procedural guarantees.

Next chapter: courts, diplomatic pressure, and collateral effects

In the immediate future, the conflict is likely to shift onto three fronts:

- Judicial: appeals and lawsuits assessing the legality, proportionality, and guarantees of the mechanism.

- European regulatory: pressure to ensure that quick blocking tools meet stricter standards for transparency, traceability, and collateral damage controls.

- Operational: if Cloudflare hardens its stance or reduces presence, there could be impacts on performance and resilience for traffic in Italy; if it cedes, it sets a precedent for other regulators to demand similar measures.

Underlying all this is a structural tension made more visible by 2026: the “economy” of the Internet depends on global actors (public DNS, CDNs, WAFs, anti-DDoS tools), but states want quick, enforceable solutions within their borders. The real game is balancing legal security, rights, efficacy, and minimizing collateral damage.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Piracy Shield and why does it affect services like DNS or CDN?

Piracy Shield is a platform linked to anti-piracy measures in Italy. In such schemes, blocking can be implemented at various points: DNS, IP, access providers, or intermediaries that facilitate service accessibility.

Why is 1.1.1.1 mentioned in the Cloudflare controversy?

1.1.1.1 is Cloudflare’s public DNS resolver. Prince argues that the Italian scheme would require actions that affect this resolver as well, increasing the risk of broad reach blockages if fine controls and quick reversals are not in place.

Can a fine on Cloudflare affect Internet performance in Italy?

Indirectly, yes, if the company reduces local infrastructure or services (e.g., server presence) as operational retaliation. However, any impact would depend on the extent of changes and available alternatives.

What is the debate around “global blocking” versus “local blocking”?

Local blocking attempts to restrict only within a country’s borders. Global blocking would require a provider to impose restrictions on users in other countries, raising jurisdictional conflicts and extraterritoriality issues.