The startup process of a computer doesn’t begin on the hard drive or the operating system. It starts earlier: in the firmware of the motherboard, that low-level software responsible for initializing the hardware, verifying that everything is in good condition, and handing control over to the system’s bootloader. For decades, this role was played by the BIOS, but for many years now, the standard in modern machines is UEFI.

Understanding the difference isn’t just a “techie” detail: it’s the reason why many installations fail, why a disk “won’t boot” after cloning, or why a USB boot works on one PC and not another.

What was BIOS and why did it dominate for so long

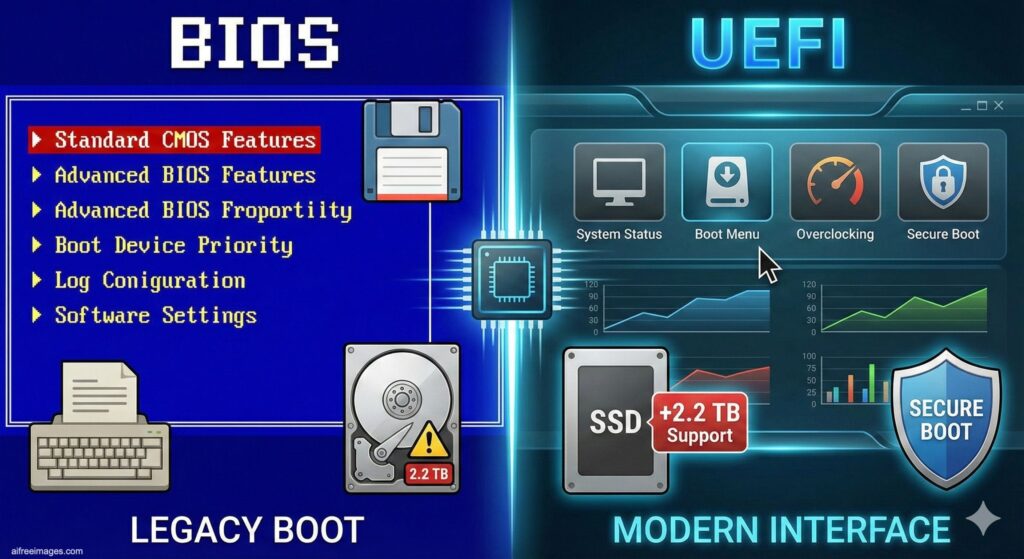

The BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) was born with the first IBM PCs and became the de facto standard for years, for a simple reason: it was the universal way to boot a compatible PC. Its job was to:

- Perform the POST (Power-On Self Test), essentially a basic hardware check.

- Initialize essential components (keyboard, controllers, video…).

- Find a boot device and load the bootloader.

The problem is that BIOS carries limitations from another era. Some of the most well-known include:

- Very basic startup and environment, inherited from old architectures.

- Traditional dependence on the MBR (Master Boot Record) scheme.

- Practical limit of 2 TB due to the classic constraints of MBR partitioning on disks with 512-byte sectors.

- Lack of security mechanisms comparable to modern standards.

It remained the standard for decades because it worked and because the entire ecosystem was built around it. But hardware and needs have changed.

UEFI: the modern standard replacing BIOS

UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) isn’t “a new BIOS,” but a different approach: a more advanced, extensible firmware prepared for current hardware. Its development is linked to EFI (originally driven by Intel) and to its standardization by the UEFI Forum. This organization established specifications that are now common in virtually every modern motherboard.

Practically, UEFI offers clear improvements:

- Native compatibility with GPT, the modern partition scheme.

- More flexible and often faster boot.

- Support for disks larger than 2 TB.

- Boot management through entries in NVRAM (instead of relying only on the disk’s first sector).

- Secure Boot, a mechanism aiming to prevent untrusted bootloaders from loading.

Additionally, UEFI has evolved from being an “option” to a requirement in current environments. A clear example is Windows 11 which mandates UEFI (and usually Secure Boot and TPM) to meet its official hardware requirements.

Legacy or CSM: the compatibility option keeping old tech alive

This is where the most confusing concept appears: Legacy.

Legacy isn’t a different firmware. It’s a compatibility mode within many UEFI implementations, known as CSM (Compatibility Support Module). Its goal is to behave “as if it were BIOS” to be able to boot:

- Old operating systems.

- Old recovery or diagnostic tools.

- Installations made with MBR that aren’t prepared for UEFI/GPT.

It was a transitional solution, very useful for years, but increasingly less needed on new hardware. Many recent models either completely remove it or have it disabled by default.

The key real-world difference: UEFI + GPT vs BIOS + MBR

Beyond definitions, the impact is seen in two main points:

- The type of disk partitioning

- BIOS typically works with MBR.

- UEFI usually requires GPT (and a special boot partition called the ESP where the UEFI loader resides).

- The way the system “finds” what to boot

- BIOS looks for a boot sector on the device.

- UEFI can use entries registered in firmware (NVRAM) and load

.efifiles from the ESP partition.

This explains why a cloned disk or a “half-created” USB can be perfectly copied yet still fail to boot if the firmware mode isn’t aligned with how the disk is prepared.

Common errors when installing or repairing a system

Here are some typical situations encountered in tech support:

- Booting from USB in the wrong mode: the installer starts, but then the system doesn’t appear in the boot menu or the structure isn’t correct.

- Disk with MBR on pure UEFI: if CSM is disabled or not present, that disk won’t boot.

- Secure Boot blocking a bootloader: especially with Linux distros or old unsigned tools (though many modern distributions are prepared).

- Broken dual-boot caused by changes in UEFI boot order or overwriting NVRAM entries.

What’s recommended today

For modern systems and current hardware, the practical recommendation is clear:

- UEFI + GPT as the standard configuration.

- Secure Boot enabled if the system and boot flow support it without issues.

- Legacy/CSM only if you need compatibility with old software or legacy installations.

Classic BIOS is essentially a part of PC history now—and the origin of many headaches that still crop up when mixing modern hardware with systems designed for another era.