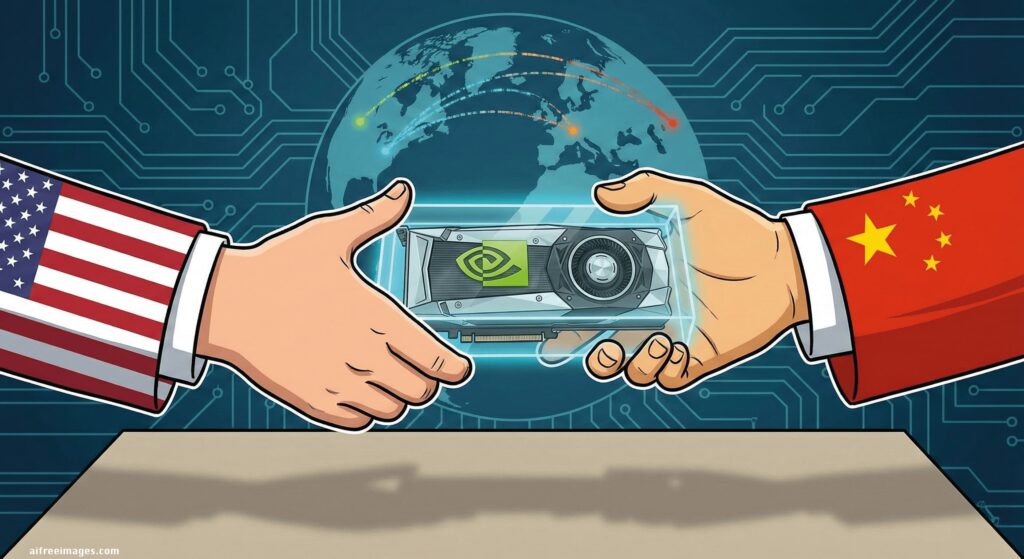

The race for Artificial Intelligence is increasingly becoming a race for chip access. And when access is restricted by decree, alternatives emerge. This is suggested by the latest information on Tencent, one of China’s tech giants, which purportedly found a legal but politically explosive way to leverage NVIDIA’s Blackwell GPUs — the same ones Washington aims to keep out of the reach of Chinese companies — without importing them into Chinese territory.

The mechanism would be as simple as it is difficult to fit into a tech war: leasing compute capacity in data centers outside China. According to research, Tencent appears to have accessed B200 GPUs (and also capacity associated with B300 in deployment plans) through a Japanese “neocloud” provider called Datasection, which mainly operates in Japan and Australia. In other words: if the hardware doesn’t cross the border but the computing power is used remotely, export controls lose some of their practical effect.

The “trick” isn’t smuggling — it’s cloud services

The key lies in fine print. U.S. restrictions have aimed to limit the sale and export of the most advanced chips to China, especially those designed for large-scale AI training and inference. However, the rise of the “GPU-as-a-service” model introduces a grey area: the Chinese company doesn’t buy the chip, doesn’t receive it, and doesn’t install it in a private data center. It uses it remotely, renting compute time in an installation in an allied or partner country.

According to reports, Datasection has secured large contracts to operate a cluster of around 15,000 Blackwell processors and to reserve a significant portion of that capacity for a reference client. Sources familiar with the agreement cited in the reports state that this client would be Tencent, operating through a channel facilitated by third parties. The financial volume is substantial: contracts reportedly exceeding $1.2 billion. This isn’t a one-off purchase: it’s a supply strategy disguised as a service.

This approach aligns with a trend that analysts have observed for months: when hardware limitations slow down big labs, the market reorganizes around who has access to installed capacity, even if it’s on another continent. By 2025, competitive advantage won’t just be about designing better models but ensuring they’re trained on the right infrastructure.

Japan and Australia: the geopolitical landscape of power

The geopolitical dimension becomes clearer when looking at the map. In a world where China is trying to accelerate its domestic chip ecosystem, companies like Tencent, Alibaba, or Baidu still have an immediate need: world-class compute capacity to train and operate competitive models. If they can’t buy the best directly, they may opt for indirect routes.

In this case, infrastructure would be located in Osaka (Japan) and Sydney (Australia), two locations with strong connectivity, regulatory stability, and strategic weight in the Indo-Pacific. This detail matters because it turns the issue into an international matter: AI power doesn’t travel in boxes; it travels through fiber optic cables.

For the United States, the issue is uncomfortable. On one hand, the “leasing” model allows the Western ecosystem to keep generating revenue and maintain technological influence. On the other hand, it undermines the original intent of export controls: to prevent strategic rivals from scaling their AI capabilities with cutting-edge technology.

What Tencent gains and what’s lost with export controls

For Tencent, the incentive is clear: gain a generational leap in performance without waiting for the local market to fill that gap. Blackwell (B200/B300) represents the new frontier in AI computing, with differences over previous generations that could be decisive in training costs, iteration times, and the ability to deploy large-scale AI products.

For Washington, the risk is that controls turn into a game of “compliance without achieving the goal.” Cloud services can transform a veto on ownership into just a change in consumption mode. And when dealing with labs with multi-billion-dollar budgets, leasing is not just a temporary workaround: it could become the preferred way to operate.

This issue is increasingly drawing political pressure. The idea that Chinese companies are using advanced GPUs, even if physically installed in Japan or Australia, could lead to new regulatory interpretations: limits per end user, load type, access control, audits, or traceability of actual usage. Essentially, it’s an attempt to extend export controls… into the service domain.

Datasection and the rise of “neocloud” as a strategic player

Another key player is Datasection, described as an emerging provider moving into AI infrastructure with large-scale agreements. A new category is consolidating in the market: companies that aren’t traditional hyperscalers but build massive GPU clusters for rental to third parties. This “neocloud” fuels on the AI craze and a fundamental fact: there’s more demand for advanced capacity than supply.

If such providers become common intermediaries, the landscape shifts: power moves from “who can buy chips” to “who can reserve clusters” and “who can deploy where regulation is more favorable.” It’s the economy of AI transformed into global logistics.

Direct economic impacts: costs, investment, and competitive edge

The story also has a financial dimension. Leasing Blackwell outside China involves:

- High recurring costs (multi-year contracts) compared to direct capital investment.

- Dependence on third parties for availability, latency, and service continuity.

- Regulatory risk: if regulations change, capacity could be restricted or rendered more expensive abruptly.

Nevertheless, for companies competing to gain market share in AI services, the calculation may be straightforward: pay more today to avoid falling behind tomorrow. It’s a common pattern in tech markets: when a critical resource is scarce, access is purchased, not ownership.

Simultaneously, NVIDIA’s position is also central: if bans to China limit direct sales, cloud services outside China can serve as a commercial safety valve — though politically sensitive. As industrial policy and security policies intersect with quarterly results, every “loophole” sparks public debate.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly does “rent Blackwell GPUs” mean if they are prohibited for China?

It means the chips aren’t exported to China nor delivered to a Chinese company. Instead, they are installed in data centers in other countries and offered as remote services, billed by usage or reserved capacity.

Is it legal for a Chinese company to use advanced NVIDIA chips from Japan or Australia?

According to reports, this mode operates in a less explicitly regulated zone because export/ sale of hardware is regulated, but the remote use of compute isn’t always covered. For this reason, it could become a target for future restrictions.

Why are major Chinese tech companies more interested in leasing than buying less powerful chips available locally?

Because the performance of cutting-edge GPUs reduces training times and costs, enables larger models, and accelerates launches. In AI, weeks can determine competitive advantage.

What impact could this have on the global price and availability of AI capacity?

If leasing becomes widespread, demand for clusters outside China could tighten the supply of advanced GPUs and push up the costs of computing services, especially for clients competing for long-term reservations.

via: wccftech