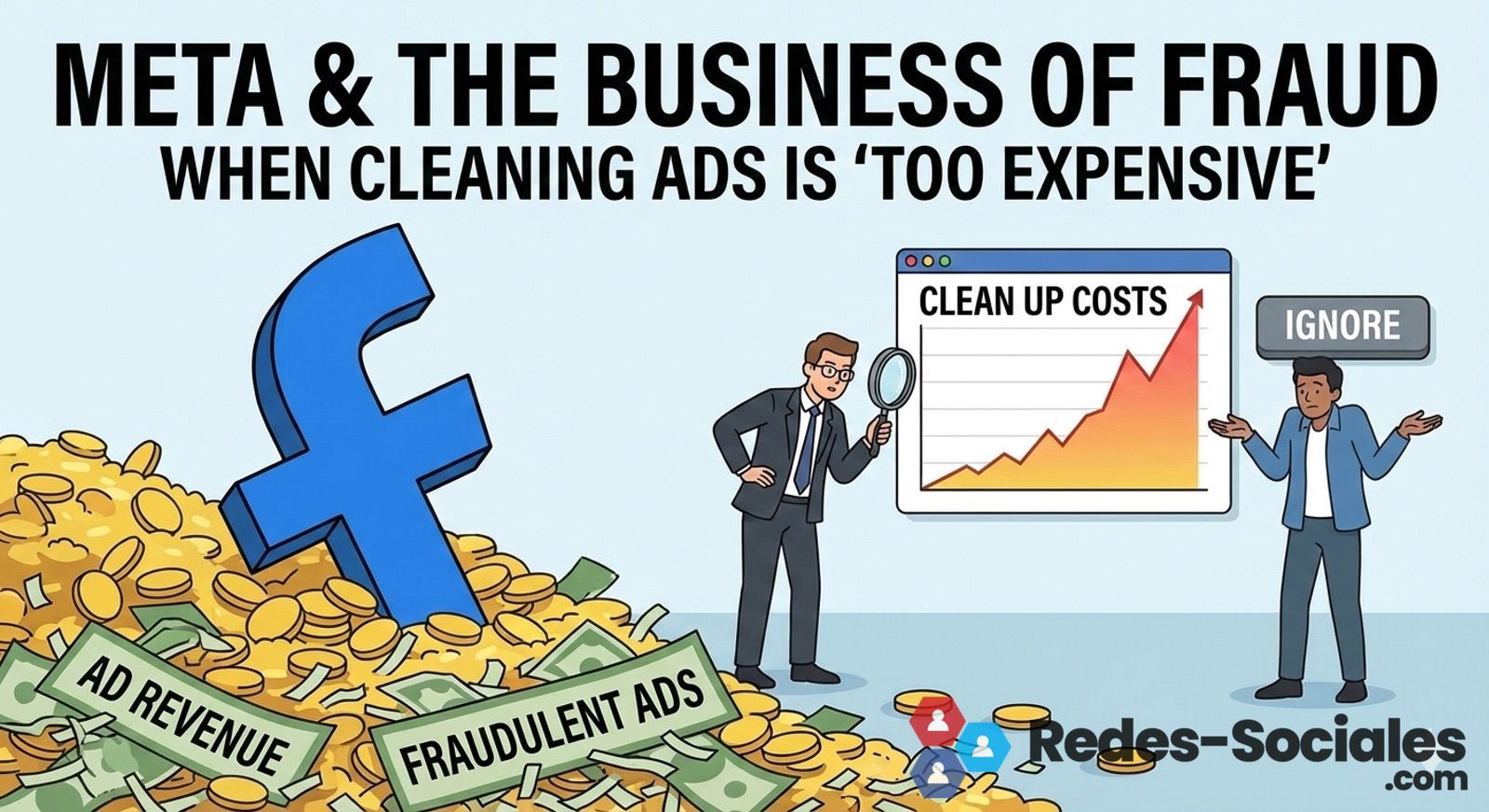

Meta has been haunted for years by an uncomfortable paradox: its platforms are simultaneously one of the world’s largest advertising showcases and a recurring channel for scams that slip through amidst legitimate ads. The question is no longer whether the company has the technical capacity to stop this — it does — but how it chooses to prioritize resources, controls, and “friction” in a market where each percentage point of revenue weighs more than the promise of a clean ecosystem.

A recent investigation by Reuters highlights a particularly sensitive issue: the advertising business linked to China and the role of intermediaries. According to the information gathered by the agency, within the company itself, it was estimated that a significant portion of advertising revenue from China was associated with scams and other prohibited content. At its peak, these ads may have represented nearly 19% of Meta’s revenue in China, translating to over $3 billion annually. This is a notable figure: it demonstrates how fraud can become “background noise” when the system is optimized to scale ad buying through layers of agencies and resellers.

According to Reuters, this mechanism operates with an almost industrial logic. Meta operates in China through large agencies that act as gateways; these, in turn, sublease or redistribute access to smaller advertisers. For a global business, this model facilitates volume, speed, and expansion. But it also multiplies risks: responsibilities become diluted, real traceability of advertisers is complicated, and malicious actors can quickly rotate identities, accounts, and creatives.

Meta even attempted a more aggressive internal initiative. Reuters details that a specialized team managed to reduce the estimated percentage of scam ads linked to China from that 19% figure to around 9% by late 2024. The technical takeaway is clear: when personnel are assigned, rules are tightened, and verification is enforced, fraud drops. But the business implication is uncomfortable: that reduction also impacts revenue, because “cleaning” entails rejecting campaigns, blocking networks of intermediaries, and accepting immediate revenue loss.

And this is where the friction point emerges—one that irritates many security analysts and much of the public: Reuters explains that after internal debates and shifts in focus, Meta halted some of those measures, disbanded the specialized team, and relaxed restrictions affecting problematic partners. Concurrently, the volume of banned ads is said to have rebounded over time. In practical terms, the message conveyed—beyond any official statement—is that intensive moderation works… but it costs money.

The context is also important: advertising fraud is no longer just the cheesy ad leading to a suspicious website. Today, it relies on sophisticated creatives, “funnels” leading to messaging (WhatsApp frequently appears as the final stage of scams), cloned pages, and increasingly, automation. In an environment where large-scale reviews depend on automatic systems, scammers play the numbers game: passing filters for hours or days with a fraction of their ads. That window can be enough to profit from campaigns, especially in schemes involving fake investments, brand impersonation, or miracle products.

The problem is far from exclusive to Meta: it’s a symptom of how ad tech has been built at scale. Nevertheless, the company is an especially relevant case due to volume and product integration (Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp). Reuters has also pointed out in other reports that fraud and ads promoting prohibited goods or services could represent a material part of the global advertising business, with U.S. lawmakers pressuring Meta to explain what measures it takes and how it measures the real damage to users.

For a technology-focused media, there’s an additional point often lost in political debates: the architecture of the system matters. When growth relies on resellers, agencies, and “supply chains” of advertising accounts, security is no longer a toggle but a structural tension. Raising verification standards, tightening KYC for advertisers, reducing the lifespan of suspicious accounts, or imposing stringent audits on intermediaries all work… but they reduce conversions, slow down new advertiser onboarding, and can penalize entire markets.

In other words: fraud isn’t just a moderation failure. It’s an externality of the advertising distribution model. And the big question for 2026 isn’t whether we’ll see more “apps,” more AI, or more automatic recommendations, but whether platforms will be willing to accept the revenue loss (and operational friction) involved in truly closing the backdoors that allow dirty money to flow.

What the Reuters investigation makes clear is an uncomfortable conclusion for the industry: when economic incentives push against, self-regulation hits a ceiling. And that ceiling is often right where the bottom line starts to hurt.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do fraudulent ads still appear on Facebook or Instagram even after being reported?

Because fraud operates at scale and accounts rotate: even if ads are removed, malicious actors reappear with new identities, creatives, and domains, exploiting windows of time before human reviews can intervene.

What role do WhatsApp and messaging play in scams originating from ads?

They often serve as a “second phase”: the ad gets the click, and the conversation shifts to messaging, where it’s harder to monitor the deception and ending the scam can be more straightforward.

How can a company detect if its brand is being used in fraudulent (impostor) ads?

Through continuous monitoring of creatives and mentions, keyword alerts, review of ad libraries where available, and a quick takedown channel (plus proactive client communication).

What measures are most effective against large-scale advertising fraud?

Strong advertiser verification, limits and audits on intermediaries, traceability of the actual beneficiary, and reducing the “lifetime” of new accounts attempting to scale spending quickly.