Storing data for decades is already challenging. Doing so for centuries—and without continuously powering a system—sounds like science fiction. However, the idea of “archiving forever” is gaining traction right as digital infrastructure experiences its most significant expansion due to artificial intelligence, video, regulation, and the need to preserve complete histories in research, health, culture, or industry.

In this context, SPhotonix emerges— a start-up linked to the University of Southampton—working with an unconventional support in modern storage: fused silica glass. The company claims its “Memory Crystal” 5D technology has moved out of the laboratory and is approaching pilot projects in data centers within the next two years, focusing on cold storage: information that needs to be preserved for many years but is accessed sporadically.

What does “5D” mean and why is glass the key?

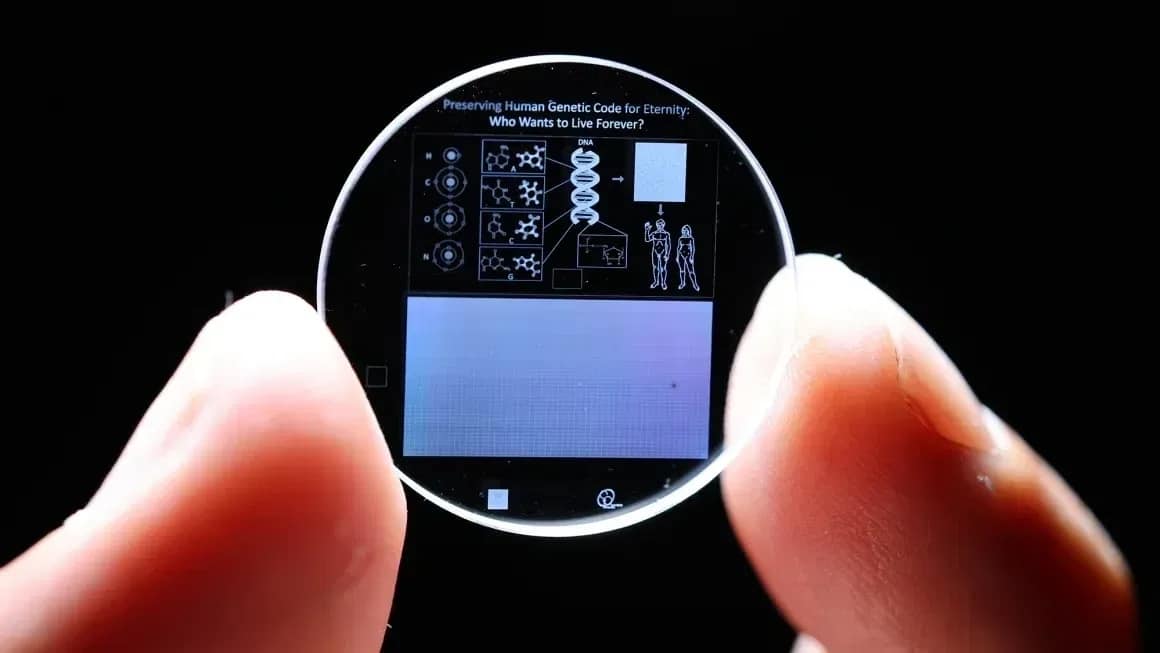

The term “5D” has nothing to do with mystical spatial dimensions but refers to how information is encoded. Instead of recording data on a surface—as in traditional optical media—the method uses a femtosecond laser to inscribe nanostructures within the glass. These five “dimensions” of encoding include three coordinates (x, y, z)—the position within the material—and two optical parameters associated with those nanostructures (orientation and intensity/birefringence), which are then read with polarized light.

This approach offers two clear advantages for ultra-long-term archiving: physical stability and environmental resistance. The University of Southampton has been promoting advances in this research area for years, highlighting that the medium can preserve information for billions of years and that, in larger formats, it can store up to 360 TB.

SPhotonix builds on this academic legacy, packaging it into a platform with industrial ambitions. According to the company, its technology can store data on a 5-inch glass disc with capacities up to 360 TB and a “cosmic-scale” theoretical resilience: approximately 13.8 billion years—the estimated age of the universe.

From “it works” to “it’s useful”: the real challenge of bringing it to data centers

Spectacular demos have always been the most eye-catching part of 5D glass storage. The ongoing challenge is the same: transitioning from laboratory milestones to a system that competes—cost-wise and performance-wise—with existing solutions.

The published data on the current state of the system offers a more realistic view. Prototypes have demonstrated write speeds of about 4 MB/s and read speeds of around 30 MB/s, which are below established archival alternatives. Nevertheless, their roadmap aims to achieve read/write speeds of about 500 MB/s within three to four years—a figure that would bring practical large-scale archive use closer.

Hardware costs are also a factor: initial costs for the writing equipment are estimated around $30,000, with about $6,000 for the reader, and the company aims to have a deployable “field-ready” reader within approximately 18 months.

With these figures, the fit seems clear: the goal isn’t to replace SSDs or production storage but to target segments where energy costs, media degradation, and long-term retention needs outweigh latency concerns. This includes national archives, digital libraries, evidence preservation, scientific repositories, or large corporate catalogs that must endure technological shifts and short hardware life cycles.

A “time capsule” archive

The “conserve for the future” narrative has also become a cultural product. SPhotonix announced it preserved the Eon Ark Time Capsule— a project by Sounds Fun in collaboration with the Berggruen Institute. The capsule contains “conversations” recorded in 2024 and 2025 and uses AI techniques to transform responses into interactive agents, enabling future generations to “dialogue” with 21st-century people.

Beyond media impact, such projects serve as showcases: proof that the medium is suitable not only for “cold” corporate data but also for preserving content with historical or patrimonial value. Simultaneously, the company announced closing a pre-seed round of $4.5 million to accelerate product development and deployment, citing advancements in its FemtoEtch technology and the goal of reaching mature, real-world-ready stages.

More contenders are entering the race: Microsoft, Cerabyte, and the fight for archival supremacy

SPhotonix isn’t alone. Major players and startups are exploring similar pathways for archival storage beyond magnetic media. For example, Microsoft has publicly shared its work on glass media within Project Silica, and companies like Cerabyte are advancing ceramic alternatives aimed at robotic libraries. The open question is whether 5D glass storage will achieve sufficient performance, read standardization, and economies of scale to shift from a “fascinating” medium to a reliable infrastructure.

What’s clear is the emerging sign: when an industry rethinks how to read data in decades—rather than months—the digital archive problem is becoming too large to solve with traditional supports.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is 5D glass storage, and why is it called “5D”?

It encodes data inside the glass using three spatial coordinates and two optical parameters associated with laser-engraved nanostructures, which are then read with polarized light.

What types of organizations benefit from “cold storage” in glass?

Organizations requiring long-term data retention with infrequent access: archives, libraries, research institutions, digital heritage, evidence storage, or large-scale corporate repositories.

What are the main hurdles for 5D glass to reach data centers?

Improving read/write speeds, reducing costs, standardizing readers/writers, and ensuring long-term retrievability through maintainable tools and documentation.

What’s the difference between storing data “forever” and being able to read it “forever”?

The support’s durability is one aspect; the other is ensuring compatible readers, documented formats, and recovery procedures that don’t depend on a single lab or provider.

via: sphotonix