An international team of researchers has developed a single electronic component capable of mimicking activity in different areas of the brain—an advancement that many experts see as a turning point for robotics and artificial intelligence hardware. The device, named transneuron, accurately reproduces the electrical patterns of real neurons and can change its “role” on the fly—something that until now was only observed in biological systems.

The work, led by Loughborough University (UK) in collaboration with scientists from the Salk Institute and the University of Southern California (USC), has been published in Nature Communications. It falls within the field of neuromorphic computing, which aims to build chips that operate more like the brain than a conventional computer.

One single component, multiple “brain roles”

The majority of artificial neurons used in current hardware are designed for a single task: filtering a signal, acting as an oscillator, firing pulses in a specific pattern… For complex tasks, thousands or millions of these units must be combined, consuming significantly more energy than the human brain and offering limited flexibility.

The transneuron proposed by the Loughborough team breaks this logic: it is a single physical device that can behave, depending on configuration, like neurons from different cortical areas involved in vision, movement planning, and motor control.

Instead of reprogramming software, the researchers adjust purely physical parameters—such as applied electric tension, temperature, and circuit load resistance—and this alters the firing pattern of the device until it closely resembles that of specific biological neurons. This “neural personality” change is achieved without adding new components or modifying the chip design.

Copying impulses from monkey neurons

To verify how closely the transneuron mimicked real neurons, the team compared its activity with electrical recordings obtained from awake monkeys. Three cortical regions were selected:

- An area specialized in processing movement.

- A region involved in planning hand movements.

- A premotor zone related to action preparation.

Each of these areas shows distinct electrical signatures, ranging from irregular, seemingly “noisy” discharges to more regular pulse trains or burst patterns, where groups of impulses are followed by silent intervals.

By feeding the transneuron electrical input signals and tuning its parameters, the researchers achieved pulse patterns nearly indistinguishable from those recorded in real neurons, with correlations reaching close to 100% in some cases. It’s not just about mimicking pulse shapes but also the rhythm, variability, and stochastic nature of the signals—key features of brain activity.

Not just imitating: also processing information

The study also shows that the transneuron doesn’t merely reproduce pre-recorded patterns but actually processes incoming information. When the input signals change, its firing rhythm adapts, just like a biological neuron responding differently to stronger or weaker stimuli.

When supplied with two different signals simultaneously, the device’s response varies based on the timing of these stimuli, demonstrating temporal integration phenomena akin to those observed in the nervous system. This kind of behavior—which in conventional hardware would require multiple artificial neurons—is achieved here with a single component.

This rich, context-dependent responsiveness is one reason the team refers to it as a transneuron: an element capable of “transiting” between various neuronal functions depending on task demands.

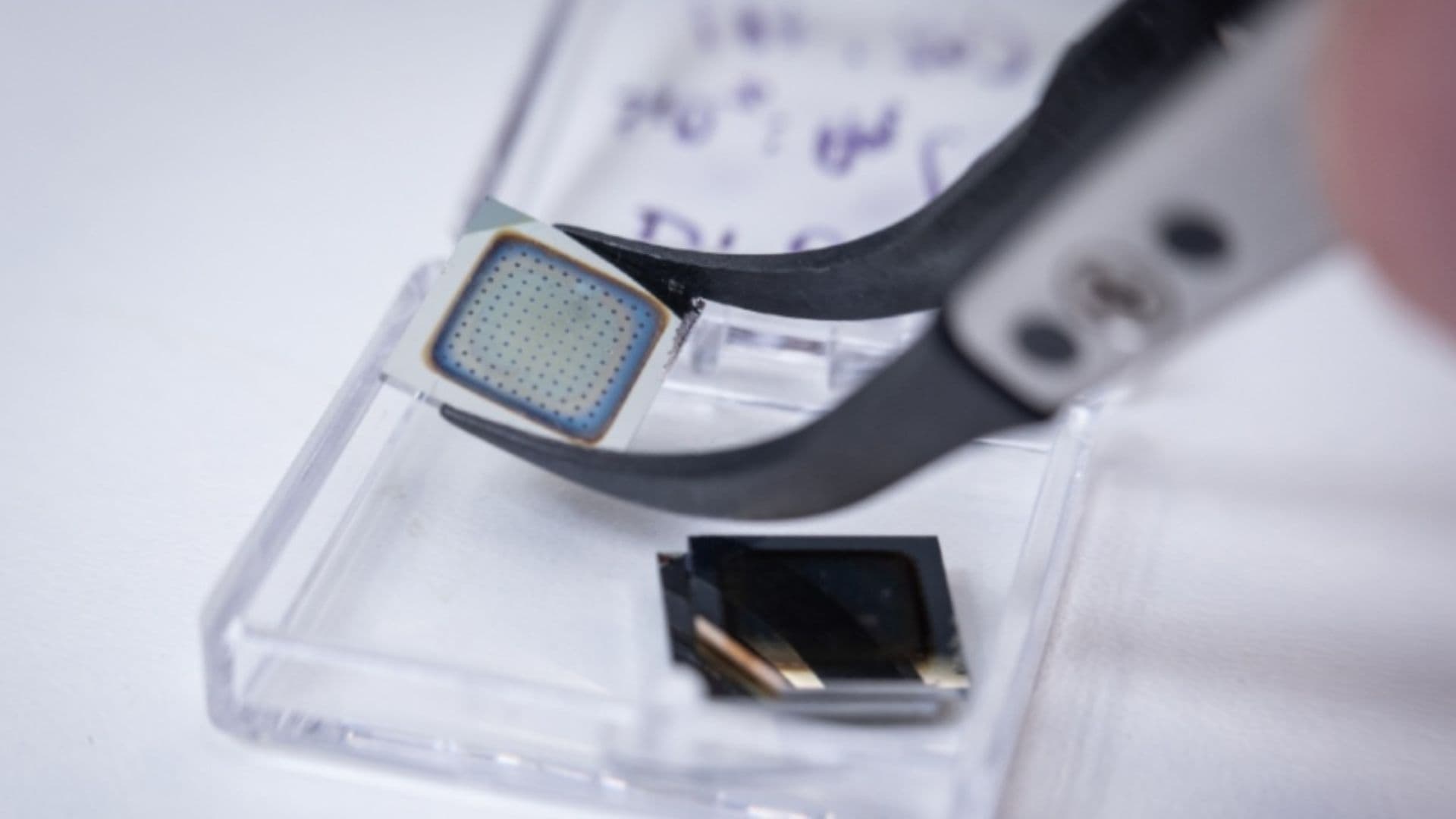

The secret: a memristor that “remembers” electricity

At the core of the transneuron lies a memristor—an electronic component whose resistance is not fixed but depends on the history of the current and voltage that have flowed through it. In this case, it is a nanoscale device where silver atoms form and break tiny conductive filaments between electrodes.

When a specific voltage is applied, these filaments form and dissolve dynamically, generating current pulses that resemble the action potentials of neurons. Changes in temperature, supply voltage, or circuit resistance enable shifting the system between different “firing regimes”: more regular, more chaotic, burst-like, etc.

This inherently dynamic and noisy behavior makes memristors especially promising for neuromorphic applications: their internal physics already resemble, to some degree, that of a complex biological system, reducing the artificial “artifice” needed to emulate brain functions.

Toward a “cortex in a chip” for more intuitive robots

The team’s next step is to move beyond a single unit and start building networks of transneurons—a potential “cortex in a chip.” Instead of large data centers running neural networks on GPUs, this type of neuromorphic hardware could be integrated directly into robots and autonomous devices.

The researchers envision machines with artificial nervous systems capable of:

- Integrating complex sensory information (vision, touch, proprioception) in real time.

- Continuously adjusting their behavior in response to environmental changes.

- Learning more efficiently with much lower energy consumption than current chips.

In robotics, this would translate to more natural movements, better reactions to unforeseen situations, and smoother interactions with humans and unstructured environments—including factories, hospitals, and public spaces.

Potential applications in neuroprosthetics and consciousness studies

Beyond robotics, the authors highlight possible medical applications. Transneuron-based devices could serve as bidirectional interfaces with the nervous system, helping to restore lost functions or supplement damaged circuits in neurological diseases.

They also suggest their use as an “electronic laboratory” for neuroscience research. With a configurable physical system that mimics real neuronal behavior, scientists could explore hypotheses about how different brain areas coordinate or what mechanisms underlie complex phenomena like unified perception or consciousness—without experimenting directly on living tissue.

For now, all of this remains at the basic research stage, but the work reinforces a growing idea: to bring artificial intelligence closer to human brain capabilities, larger software models won’t be enough. It will also require a new generation of hardware that more closely resembles the brain’s physical substrate.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is a transneuron, and how does it differ from a conventional artificial neuron?

A transneuron is a single electronic device capable of emulating various types of biological neurons by adjusting only physical parameters (voltage, temperature, resistance). Conventional artificial neurons are typically designed for a fixed function within a circuit, whereas the transneuron can be reconfigured to assume different roles (visual, motor, premotor) without changing hardware.

Why is this breakthrough important for robotics and AI hardware?

Because it allows for the conception of chips where a few physical units perform functions that today require thousands of artificial neurons. This promises more compact systems, lower energy consumption, and richer, more adaptable responses—ideal for robots that need to perceive their environment and react in real time, with less reliance on cloud computing or large data centers.

What role do memristors play in these artificial neurons?

Memristors are key to providing memory and dynamics: their resistance changes based on current and voltage history. In transneurons, the formation and rupture of silver filaments produce electrical pulses similar to biological action potentials. By adjusting memristor conditions, different firing patterns can be generated, allowing emulation of various brain regions.

When might commercial robots with nervous systems based on transneurons appear?

This is still very early-stage research, with experimental devices in laboratory settings. Before commercial deployment, challenges such as large-scale manufacturing, integration with other electronics, long-term reliability, and regulatory approval (particularly for medical uses) need to be addressed. In the short- to medium-term, its main impact will be as a research platform for new neuromorphic architectures.

Sources:

Nature Communications (article “Artificial transneurons emulate neuronal activity in different areas of brain cortex,” 2025).

Notes and press releases from Loughborough University on transneuron and neuromorphic computing.

International technology media coverage on the development of the transneuron and its applications in robotics and AI.

via: Interesting Engineering and Mentes Curiosas