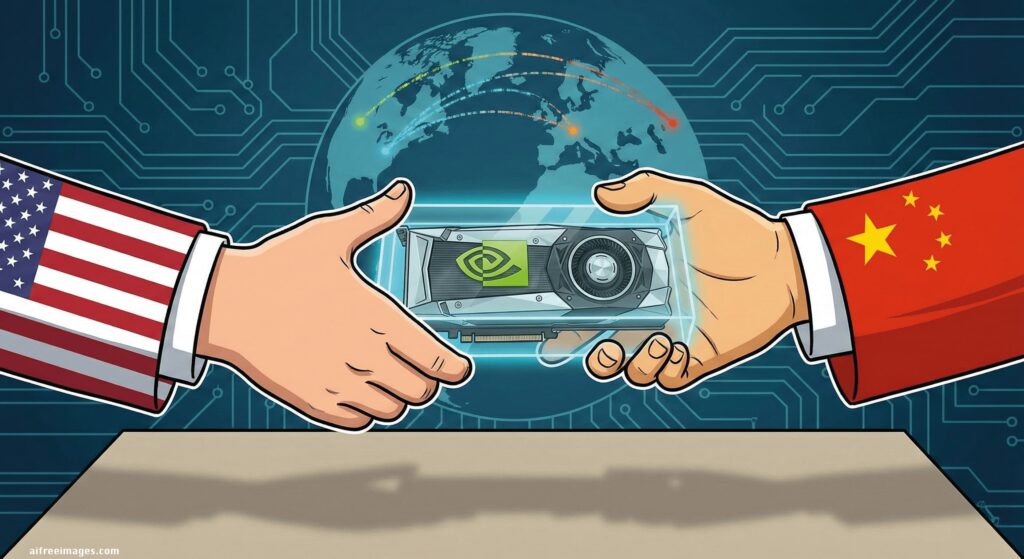

The United States is preparing for a delicate shift at one of the most sensitive technological borders of the moment. The Trump administration is considering allowing NVIDIA to once again sell its most advanced AI GPUs, such as the H200, to China, after years of increasingly strict controls designed precisely to prevent it.

On paper, this move appears as an attempt to normalize trade relations after a truce in the tech war. In practice, it raises an uncomfortable question for the entire sector:

How meaningful is it to limit China’s access to AI chips if Washington keeps rewriting the rules every few months?

From Turning Off the Tap to “Opening It a Little”

Since 2022, the U.S. strategy has been clear: to curb China’s AI progress by restricting access to high-performance semiconductors and the machinery needed to produce them. First, the A100 and H100 were banned; then the cut-down versions, A800 and H800; later, even models tailored for China, like the H20, appeared on the list of sensitive products.

The result was that, within months, NVIDIA went from controlling nearly the entire Chinese AI GPU market to almost zero share, while major domestic tech companies accelerated the development of local alternatives and looked for indirect ways to acquire American hardware.

However, alongside this tightening, China has demonstrated it hasn’t remained idle:

- It has launched plans to build around thirty AI data centers in regions such as Xinjiang and Qinghai,

- with the declared intention of using more than 100,000 NVIDIA H100 and H200 GPUs, according to investment documents and journalistic investigations.

All despite official bans on selling these chips to the country.

Now, with a one-year commercial ceasefire on the table and a somewhat less tense environment, the U.S. Department of Commerce is exploring allowing the export of the H200, maintaining certain red lines but opening a door that seemed sealed until recently.

NVIDIA’s Dilemma: China as Risk… and Opportunity

For NVIDIA, China is a pure contradiction.

On one hand:

- The country accounted for about a quarter of the revenue from the company’s data center business.

- It hosts some of the most ambitious AI infrastructure projects in the world, with plans involving dozens of data centers and over 115,000 high-end GPUs.

On the other:

- Regulatory pressure in the U.S. has forced NVIDIA to act as if China were, in practice, a lost market.

- Every attempt to offer a “de-fanged” chip specifically designed to comply with regulations (like the A800, H800, H20) has faced new rounds of restrictions.

Allowing the sale of the H200 now would shift the dynamics:

- NVIDIA would regain access to a huge market at a time when its competitors — both Western and Chinese — are ramping up more.

- Washington would send a message of calculated flexibility: it’s permitted to sell, but under conditions that maintain the supposed U.S. technological advantage.

The question is whether that balance is truly achievable or if, as critics in the U.S. Congress argue, partially opening the tap will actually strengthen the very actor it seeks to contain.

China Has Already Shown What It Can Achieve with Fewer GPUs

The argument from those cautious about this move is straightforward: China doesn’t need equal conditions to be competitive.

The most cited example in recent months is DeepSeek R1, an AI model that has surprised many with its performance despite reportedly being trained with significantly fewer NVIDIA accelerators than comparable U.S.-based projects.

If, with limited access to high-end GPUs, the Chinese ecosystem has been able to:

- train competitive models,

- build massive AI infrastructure in the desert,

- and maintain plans for over 100,000 GPUs in a single wave of data centers,

allowing the direct sale of the H200 could be the final push that widens the AI gap with the U.S.

From a national security perspective, the risk is clear: The same GPUs used to train language models can also be used for military simulations, signal analysis, or command and control systems. And once hardware crosses borders, effective control over its actual use is very limited.

A Two-Front Game: Chips versus Rare Earths

There’s another factor complicating this landscape: raw materials.

China controls a significant share of global production of rare earth elements and critical materials used in manufacturing chips, magnets, batteries, and electronic equipment. Washington can restrict GPU sales, but Beijing has tools to strangle supply chains for key inputs if it perceives excessive pressure.

This makes any decision on AI exports a kind of precarious balancing act:

- Too much blocking, and China accelerates its self-sufficiency strategy and responds with measures on raw materials;

- Too open, and China’s computational capacity — particularly in AI — is boosted, which the U.S. considers strategically vital.

Ultimately, it’s a continuous negotiation where both sides blend geopolitics, economics, and security at every step.

Is It Still Worth Playing the “Patchwork War”?

From a technological standpoint, the current dynamics are somewhat absurd. Every time regulators draw a line — “this performance level cannot be exported” — manufacturers design a chip that stays just below that threshold. When that chip becomes mainstream, new restrictions are imposed.

Meanwhile, the market adapts:

- Gray markets and intermediary networks appear in third countries,

- Local chip projects multiply—less efficient but “good enough,”

- And big tech companies learn to operate with hybrid hardware: partly American, partly Chinese.

If the sale of the H200 to China is finally authorized, the implicit message will be that red lines weren’t so definitive; that, ultimately, economic realities (sales, corporate pressure, trade agreements) weigh more than strict security concerns.

For the tech media, the takeaway is clear: export policies are turning into a patchwork system, more reactive than strategic, with governments and companies improvising on the fly.

What the Tech Ecosystem Should Be Worried About

Beyond the Washington–Beijing tug-of-war, there are several points the sector should monitor closely:

- Technological fragmentation

If each bloc (U.S., China, possibly others) ends up with its own stack of hardware, software, and standards, interoperability costs will soar, and innovation could slow down where international collaboration was key. - Regulatory insecurity

Frequent changes — bans, conditional approvals, reversals — hinder long-term investment and project planning, for hyperscalers and smaller firms building models for legitimate uses. - The race to “bigger and bigger”

News of data centers with 100,000 GPUs in Chinese deserts or Western superclusters with similar capacity isn’t just about raw computing power: it signals enormous energy consumption, strain on power grids, and environmental impact. - Lack of robust technical control mechanisms

Unless there are solid solutions — for example, firmware licensing models that limit certain uses regardless of GPU location — much of the export debate will remain symbolic: a mix of formal restrictions and very different realities on the ground.

A Turn That Europe and the Rest of the World Can’t Ignore

If the U.S. relaxes controls and NVIDIA partially re-enters the Chinese AI GPU market, it will transcend a bilateral issue.

- For Europe, attempting to build domestic “AI factories” with tens or hundreds of thousands of GPUs, the move reshapes the competitive and access landscape for hardware.

- For other countries, it signals that high-end AI rules are negotiable, depending on political timing and who’s in the White House.

In this context, relying solely on U.S. or Chinese planning is risky. Tech ecosystems that seek stability need to diversify suppliers, build their own capabilities, and demand clearer, more predictable export frameworks.

In Summary

Allowing NVIDIA to resell cutting-edge AI GPUs to China may seem, in the short term, like a pragmatic move: more business for a key company, less immediate tension, some formal control.

But in the medium and long term, it risks entrenching a dangerous pattern:

a chip policy that swings between outright bans and partial openings without a coherent strategy for the kind of global AI ecosystem we want to build.

The crucial question for the tech industry today isn’t just whether China will access the H200 but whether the world wants to decide the future of AI based on election cycles and specific tensions—or if it can set stable, transparent rules aligned with the risks and opportunities of the next decade.