Forty years ago, on November 20, 1985, Microsoft launched a “graphical layer” for MS-DOS that few could have imagined would define an era: Windows 1.0. That software, limited and clumsy by today’s standards, would eventually become the go-to operating system for PCs, bringing computing closer to millions of people who had never used a command line.

Four decades later, Windows remains synonymous with personal computers. Its history is also a story of how an idea, improved version after version, can transform an entire market.

From raw text to windows: the context that made Windows possible

In the mid-1980s, using a personal computer was almost a craft. No icons or menus: just a black screen and commands to memorize. Mistyping a letter could mean starting the process from scratch. It was far from being an “user-friendly” tool.

But long before, in the 1960s, some had already envisioned something different. Researcher Douglas Engelbart, at Stanford Research Institute, conceived a system based on:

- Windows

- Icons

- a pointer device: the mouse

On December 9, 1968, during the famous “mother of all demonstrations”, Engelbart showcased many ideas we now take for granted: mouse, windows, hypertext, collaborative work… That demonstration became a reference for an entire generation of engineers.

Building on this legacy, Apple launched the Macintosh in 1984 with a highly advanced graphical interface for its time. The problem was the price: it remained an expensive product targeted at a limited audience. Microsoft saw an opportunity: to bring “mouse-and-windows” computing to the IBM PC and compatibles, much more affordable and with a rapidly expanding software ecosystem. That’s how the Windows project was born.

Windows 1.0: a modest but decisive first version

Technically, Windows 1.0 wasn’t a full operating system but a graphical layer that ran on top of MS-DOS. The user still depended heavily on DOS, but a new environment with windows and mouse was overlaid, managed by the program MS-DOS Executive.

The launch price was around $99 USD, a significant amount in 1985.

The interface had notable limitations:

- Windows could not overlap freely; they were tile-organized.

- Menus were not very intuitive: you had to hold down the mouse button to keep them open.

- The system response could be sluggish, especially with multiple applications open.

Hardware requirements were also demanding for the time:

- Intel 8086 or 8088 CPU

- Minimum 256 KB RAM (512 KB recommended)

- Graphics card

- Two double-sided disk drives or a hard drive

Many users quickly noticed these limitations if their computers weren’t well-equipped. Compared to today, where Windows 11 requires at least 4 GB RAM, the gap in capability between those PCs and current ones is enormous.

The value of early applications: anticipating user needs

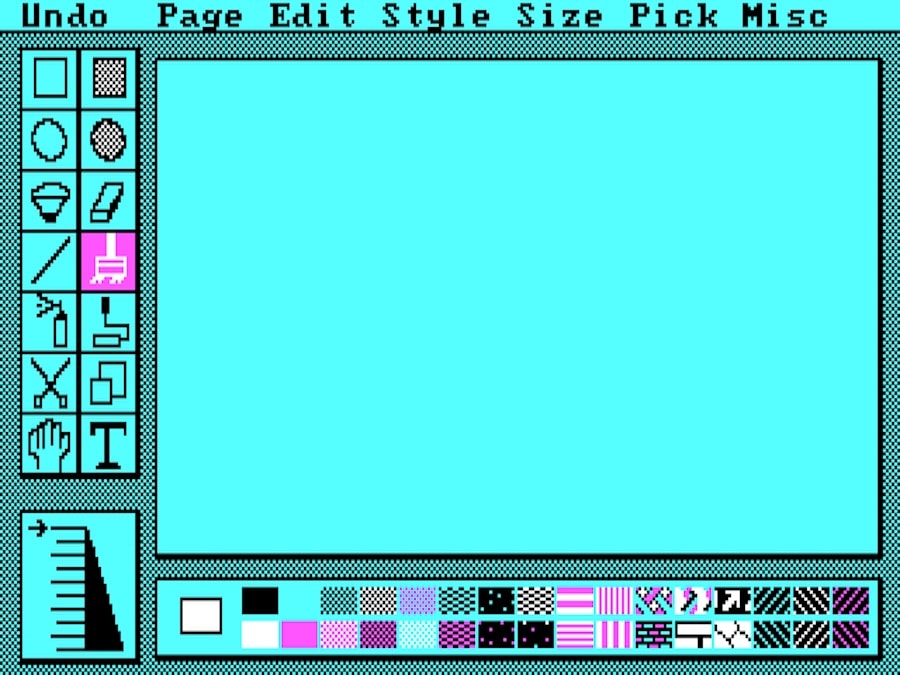

Despite its shortcomings, Windows 1.0 shipped with a small set of applications that clearly pointed toward Microsoft’s future vision:

- Paintbrush, predecessor of Paint, allowed simple drawings.

- Notepad and Write offered different levels of text editing.

- Calculator, still present today, handled basic operations.

- An alarm clock, a terminal, Cardfile (a small database of cards), the clipboard manager, and a print manager completed the set.

Today, those tools seem almost toy-like, but in 1985 they painted a new scene: a PC not just for technical tasks but also for writing, accounting, organizing information, and creating simple graphics—all within a visual environment.

What’s remarkable is that many of these concepts have persisted. Paint and Notepad remain—they’re updated but recognizable. That shows Microsoft’s early success in identifying the basic tools the average user needed.

Criticism, sluggishness… and a key decision: not giving up

The debut of Windows 1.0 wasn’t an overwhelming success. In fact, feedback was quite lukewarm.

- It was criticized for its slowness, especially with multiple applications open.

- There was a lack of native Windows software; most programs remained DOS-based.

- Compared to the Macintosh, its graphical proposal seemed less polished.

Some analysts at the time described using it on PCs with 512 KB RAM as “slower than molasses in the Arctic”—a harsh metaphor but illustrative of the frustration it could provoke.

The difference was in Microsoft’s reaction. Instead of dismissing it as a failed experiment, the company decided to persist and improve:

- Refined the 1.x series with small updates.

- Launched Windows 2.0, with improvements in windows, keyboard shortcuts, and graphics support.

- And in 1990, came Windows 3.0, the real turning point.

Windows 3.0 delivered a much more appealing graphical interface, better memory management, smoother performance, and came at a perfect time when hardware was more affordable and powerful. This combination made Windows the natural choice for millions of users and businesses.

The ecosystem was everything: how Windows conquered homes and offices

The ultimate success of Windows isn’t just about its interface, but about the ecosystem built around it:

- The open architecture of the IBM PC allowed many manufacturers to release compatible machines, lowering prices and increasing options.

- Windows benefited from this diversity: it could be installed on machines from countless brands.

- Software developers quickly saw the potential of a mass market and started releasing Windows applications at a rapid pace.

In the 1990s, the combination of inexpensive compatible PCs and a flood of software—office suites, design, accounting, CAD, business management, gaming…—made the Windows PC the de facto standard in both business and home environments.

Companies understood that it was easier to find hardware, software, and trained professionals for Windows than to adopt more closed or niche alternatives. The home user also got a machine versatile enough for work, gaming, browsing the Internet, or managing photos.

From Windows 1.0 to Windows 11: science fiction turned routine

Looking back, the difference between Windows 1.0 and Windows 11 is enormous:

- From a graphical overlay on DOS to a full operating system with advanced memory management, multi-level security, and support for 64-bit architectures.

- Multitasking is real and smooth; network and internet connectivity are built-in; multimedia support allows high-res video playback and demanding gaming.

- Cloud integration, remote desktops, virtualization, and AI-based features would have sounded like science fiction in 1985.

Yet, the core concept remains instantly recognizable:

- An desktop

- Windows that open and close

- Icons representing files and apps

- A mouse (or touch equivalent) as the main interaction tool

The evolution has been substantial, but the central idea —making the computer resemble more an office desktop than a cryptic terminal— remains intact.

The legacy of Windows: democratizing computing

Celebrating 40 years of Windows also means recognizing its role in democratizing computing. It wasn’t the most elegant or “pure” system technically, but it was the one that made using a computer no longer a reserved act for experts.

Today, Windows 1.0 is a historical curiosity we can run in emulators out of nostalgia. Microsoft occasionally plays with that past, like the Windows 1.11 app inspired by Stranger Things to revive the 80s aesthetic.

But the true legacy lies elsewhere: forty years on, Windows remains the dominant desktop system, present in millions of workstations, laptops, and classrooms. In a sector where products appear and vanish within a few years, that continuity is notable.

A lesson for the future: good ideas need time

The history of Windows offers several lessons:

- The original concept by Engelbart didn’t succeed overnight, but it was the seed of everything.

- Xerox PARC, Apple, and later Microsoft refined and developed that vision until it became viable and widespread.

- Success didn’t come with version 1.0 but after a series of continuous improvements, listening to the market, and leveraging the right hardware moments.

In an era obsessed with “shock and awe” and instant disruption, Windows’ 40th anniversary reminds us of a quieter but equally important truth: sometimes, the winning strategy is evolving steadily, fixing errors, and sticking with an idea when others have written it off.

Forty years after that first floppy disk version, Windows proves that with vision, patience, and a robust ecosystem, it’s possible to truly change the course of personal computing history.

Frequently asked questions: 40 years of Windows

When was Windows 1.0 launched, and what were its hardware requirements?

Windows 1.0 was officially launched on November 20, 1985, in the United States. To run it, you needed an Intel 8086 or 8088 processor, at least 256 KB of RAM (512 KB recommended for decent performance), a graphics card, and two double-sided disk drives or a hard drive. Its price was around $99 USD, which was significant at the time.

If it was so innovative, why did Windows 1.0 have a modest initial reception?

Because the practical experience left much to be desired: the system was slow, there were few applications designed specifically for Windows, and DOS software compatibility wasn’t always ideal. Additionally, the Macintosh offered a more polished graphical interface. Still, Microsoft persisted, and the improvements introduced in Windows 2.x and especially in Windows 3.0 eventually changed perceptions of the product.

What applications did Windows 1.0 include, and which have persisted today?

Windows 1.0 included Paintbrush (predecessor of Paint), Notepad, Write, Calculator, a clock, a terminal, Cardfile, a clipboard manager, and a print manager. Several of these ideas have survived: Paint and Notepad are still included in modern Windows versions, though heavily evolved from their original forms.

What changed between Windows 1.0 and Windows 3.0 that made the system a standard?

Almost everything that mattered:

- The interface became clearer and more attractive.

- The performance improved significantly.

- The hardware was already more powerful and affordable, making graphical interfaces more viable daily.

- The third-party software catalog exploded in size.

With these factors combined, Windows shifted from an experimental project to the de facto standard for PCs, both in businesses and homes.