The fight against climate change has placed renewable energy, nuclear power, and storage technologies at the center of global debate. Solar panels, wind turbines, lithium-ion batteries, and next-generation nuclear reactors are symbols of a cleaner future. But behind this revolution lies a less visible reality: the energy transition relies heavily on intensive mining of critical minerals, whose extraction, geographic concentration, and environmental costs pose enormous challenges.

A material dependency far greater than fossil fuels

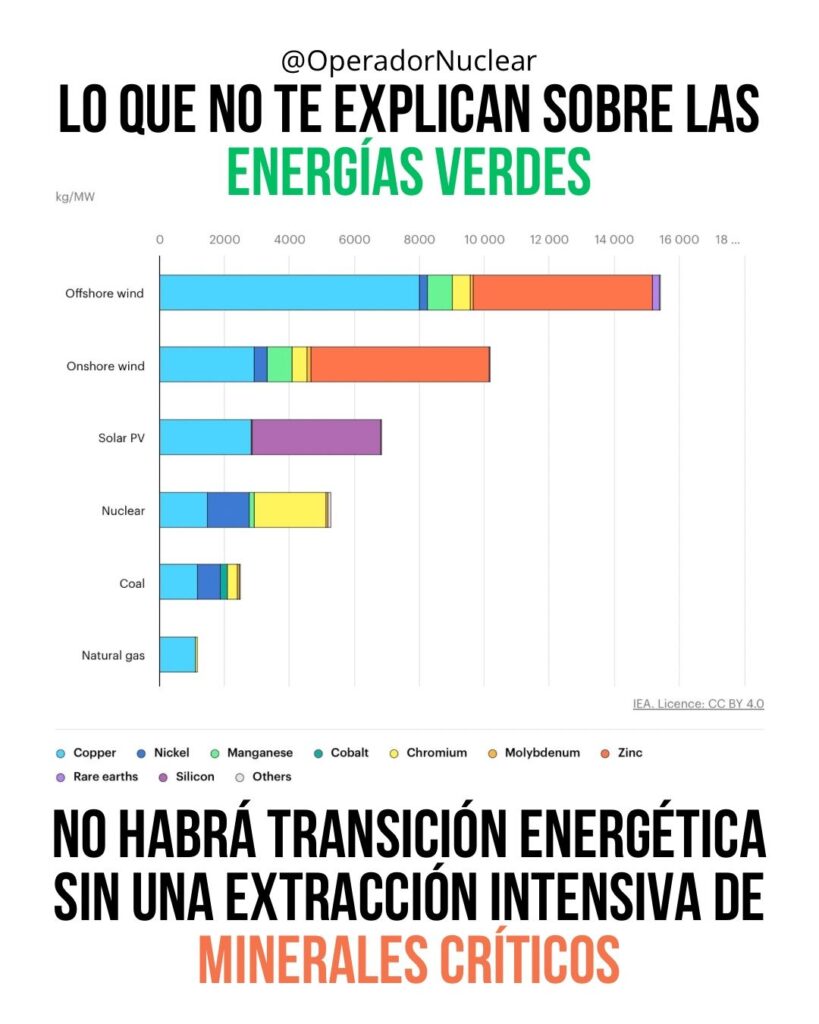

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that low-carbon technologies require 2 to 10 times more minerals than fossil fuels to produce the same amount of energy.

- A gas plant: less than 1 ton of minerals per megawatt installed.

- A coal plant: 2 tons.

- A photovoltaic solar plant: over 6 tons.

- Land-based wind: 10 tons.

- Offshore wind: up to 15 tons.

- Nuclear: about 5 tons.

The difference is significant: achieving climate goals by 2050 will require multiplying the global demand for lithium by 40, nickel by 20, and copper by more than 25, according to IEA projections.

The new geopolitics of minerals

While the 20th century was shaped by oil, the 21st could be defined by lithium, cobalt, rare earths, and copper. The extraction map for these resources is highly unequal:

- Cobalt: over 70% comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- Lithium: concentrated in the “lithium triangle” (Chile, Argentina, Bolivia), with China and Australia as key players.

- Rare earths: China controls over 60% of production and nearly 90% of global refining.

- Copper: Chile leads with over 25% of global production.

This creates a new strategic dependence, already a concern for the European Union and the United States, which have enacted specific laws to ensure more secure and diversified supply chains.

The environmental and social cost of mining

“Green energy” has a dark side. To obtain one ton of copper, about 200 tons of rock need to be processed, and for cobalt, up to 1,500 tons. This entails deforestation, pollution emissions, water consumption, and risks to local communities.

In countries like the DRC, artisanal cobalt mining is linked to child labor and precarious working conditions, sparking an ethical debate about the true “cleanliness” of the supply chains powering the energy transition.

Batteries and electric mobility: the demand epicenter

Electric cars symbolize change but also pose the greatest challenges. A 70 kWh lithium-ion battery on average requires:

- 62 kg of lithium

- 35 kg of nickel

- 20 kg of manganese

- 14 kg of cobalt

- 85 kg of copper

According to the IEA, an electric vehicle needs six times more minerals than an internal combustion engine car. With an expected 200 million electric vehicles on the road by 2030, pressure on these resources will be unprecedented.

Nuclear and renewables: different material footprints

While nuclear power offers high energy efficiency with a smaller material footprint, solar and wind — especially offshore — lead mineral demand. This doesn’t mean they should be abandoned but that their deployment must be accompanied by recycling policies, material innovation, and supplier diversification.

The invisible factor: the electrical grids

The transition is not just about generation; it’s about transmission. Currently, there are about 70 million km of power lines worldwide, containing 150 million tons of copper and 210 million tons of aluminum.

By 2040, capacity doubling of the grids will be necessary, further increasing demand for metals.

Hydrogen, AI, and new consumption

The push for green hydrogen will require minerals such as platinum and palladium for fuel cells. Additionally, the rise of artificial intelligence and data centers is boosting the need for chips and servers, multiplying demand for aluminum, steel, copper, and rare earths.

The recycling opportunity

Recycling will be crucial to reduce mining pressure. Today, over 75% of aluminum and much of the copper are recovered, but less than 1% of lithium and rare earths. Without technological advances in this field, sustaining growth will be difficult.

Conclusion: the transition is not free

A low-carbon future is non-negotiable to curb climate change but will be material-intensive. Critical minerals have become the new oil, and responsible management will distinguish between a sustainable energy transition and one that repeats past mistakes.

FAQs

1. What are critical minerals?

Minerals essential for the energy transition, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earths, and copper.

2. Why are they such a concern?

Because their extraction is highly concentrated in a few countries, creating dependency risks and geopolitical conflicts.

3. Are renewables less sustainable because they need more minerals?

Not necessarily; they remain key to decarbonization. However, their deployment must be paired with responsible mining, recycling, and diversification.

4. Can recycling solve the problem?

It will be part of the solution, but currently, large-scale recovery, especially of lithium and rare earths, remains economically unviable. Advances are needed.

_vía: LinkedIN (image: Nuclear Operator) and Mentes Curiosas_