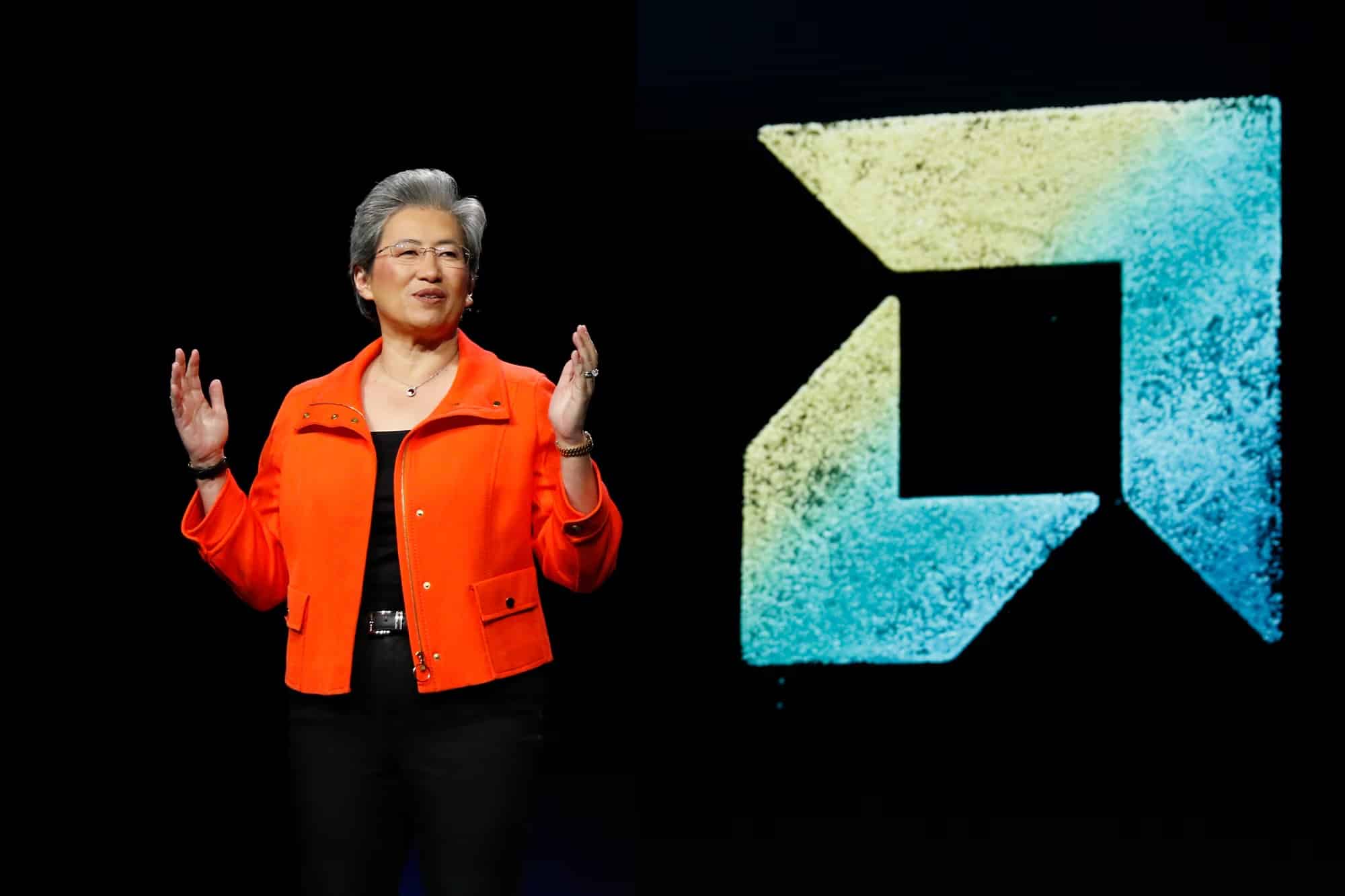

The CEO of AMD, Lisa Su, has publicly acknowledged that chips produced at TSMC’s Arizona plant are more expensive than those manufactured in Taiwan. However, she defends this extra cost as “a strategic investment” that the company is willing to make.

In an interview with Bloomberg, Su revealed that the production cost of the American chips is “more than 5% but less than 20%” higher, though she noted that the benefit lies in “the resilience of the supply chain,” a factor that gained vital importance after the pandemic.

“We’ve learned that it’s not just about seeking the lowest cost but also about considering the reliability and resilience of our supply chains. Manufacturing in the U.S. is more expensive, yes, but it’s also a sound long-term investment,” she stated.

The TSMC plant in Arizona, built with support from the CHIPS and Science Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 2022, has already begun production of 4-nanometer (N4) chips this year. Industry sources say that the quality and performance of these chips are comparable to those produced at Taiwan facilities, although with higher operational costs due to factors such as:

- Higher wages in the U.S.

- Stricter labor and environmental regulations

- Lower industrial density compared to Asia (less mature supplier ecosystem)

- Greater initial investment in talent and specialized equipment

Despite these costs, production is committed through at least 2027, with clients like Apple, AMD, and Nvidia competing to secure priority access to “Made in USA” silicon.

For companies like AMD, price isn’t the only factor. In the current climate — characterized by geopolitical tensions between China and Taiwan, global logistical risks, and increasing demand for infrastructure for AI, cloud, and high-performance computing — having a secondary manufacturing source in the U.S. is a strategic safeguard.

“If we want to ensure that critical computing infrastructure in the coming years doesn’t depend on a single country or region, we need to diversify manufacturing—even if it means paying more,” Su explained.

Additionally, the CEO mentioned that part of this higher cost is being offset by federal tax incentives and state programs, making this “a sensible investment” within the overall total cost of ownership of the systems AMD develops.

Su estimates that manufacturing chips in the U.S. costs between 5% and 20% more, which aligns with independent estimates. For example, a recent Boston Consulting Group study estimated that wafer fabrication costs in the U.S. could be 10% to 15% higher than in Asia, depending on the chip type, technology node, and volumes.

| Cost Factor | Taiwan | Arizona (estimated) | Approximate Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labor | Low | High | +200% |

| Energy & Water | Low | Medium | +25–50% |

| Environmental Regulations | Flexible | Strict | +15–20% |

| Public Subsidies | Limited | High | -10–15% |

| Total Cost per Wafer (N4) | 100 | ~110–120 | +10–20% |

Despite this, demand for capacity in the U.S. is rising rapidly, demonstrating that industry leaders are willing to bear these costs for benefits like technological sovereignty, reduced geopolitical exposure, and greater predictability.

TSMC has confirmed that Apple was the first customer to reserve capacity in Arizona, and now AMD and Nvidia are following as major beneficiaries. AMD expects to receive its first chips by late 2025, likely for strategic products such as EPYC processors, Ryzen, or Instinct accelerators for AI.

Nvidia, meanwhile, has already begun using part of the U.S. production for its Blackwell family, strengthening the U.S. position as an alternative manufacturing node compared to Asia.

The U.S.-driven technological reindustrialization aims to right decades of offshoring. In 1990, the U.S. produced 37% of the world’s semiconductors; by 2020, that had dropped to 12%. With the CHIPS Act and investments from giants like Intel, TSMC, Samsung, and Micron in American soil, the country hopes to regain some control lost over the years.

For Su, this strategy is not solely geopolitical: “It’s a matter of economic and operational security. In a world where AI, edge computing, and autonomous systems depend on a robust supply chain, being able to produce critical chips near the point of consumption is priceless.”

“If everyone is competing for the same technological resources, securing them locally is a logical step. It’s not just about efficiency; it’s about control and resilience,” she concluded.

Although manufacturing in the U.S. is more costly, AMD’s approach reflects a paradigm shift in the semiconductor industry. In a more volatile world, cost isn’t the only factor. Gaining sovereignty, stability, and control may be more valuable than what’s lost in the financial balance sheet.

In that context, paying 10% more for a chip could be the best strategic decision a tech company could make in 2025.

via: tomshardware